Comments

Header

News from Shin Kaze

November 2025

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance is an organization dedicated to the practice and development of

Aikido. It aims to provide technical and administrative guidance to Aikido practitioners and

to maintain standards of practice and instruction within an egalitarian and tolerant structure.

|

|

Table of Contents

Introduction

Introduction

Welcome to the November 2025 edition of the Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance Newsletter, a vibrant compilation of insights,

humour and reflections to fuel our global Aikido community. Below is a brief outline of the articles in this issue.

- Rafael Pacheco Shidoin's "Recognition by the Chancellor of Japan" recounts his involvement since 2015 in

Venezuela's "Japan in Aragua" event, earning honors from Japanese institutions.

- Roxana Gramada's "Be the Happy Warrior" offers a heartfelt meditation on embracing seminars and practice with joy and

resilience amid personal and societal challenges, guided by principles of growth and authenticity.

- Gordon Hannah's "Ne-waza in Aikido" advocates for incorporating ground techniques to honor the art's martial roots,

detailing osae, shime, and kansetsu waza in line with traditional principles.

- The "Book Corner" presents Chapter 5 on Ukemi from Mitsunari Kanai Shihan's "Technical Aikido", detailing breakfalls

and rolls for uke-nage harmony.

- Jutta Bossert's comic "Aikido Animals: The Blocker" satirizes stubborn training attitudes that block flow.

- Enrique Silvera's "Fishing without Bait" warns against dojo poaching, stressing loyalty and ethics in cross-school visits.

- "Dojos Granted Provisional Member Status" welcomes Argentina's Santiago del Estero Aikikai and Ukraine's Kyiv Aikido Club.

- Leandro Obligado's "My History in Aikido" traces his 30-year path from Córdoba.

- "Memories of a Tatami, Spirit of a Dojo" by Obligado and Aldo Heredia evokes their dojo's humble origins to vibrant legacy.

- Mykola Yemelianov's "Kyiv Aikido Club" highlights the club's development and resilience.

- "Reporting Aikido Injuries" promotes our anonymous database for safer practice.

This issue inspires us to train mindfully and connect deeply—explore it all and send us your contribution for the next issue!

|

|

Art. 2

Recognition by the Chancellor of Japan

By Rafael Pacheco Shidoin

Dojo-cho, Venezuela Aikido Kokyu Ho Dojo, Maracay, Venezuela

Approximately 37 years ago, I began practicing Aikido. Two years later, I had my first encounter with the Japanese Embassy in Venezuela during an event where several Iaijutsu and Jodo masters were present, invited by the embassy. It was a significant event, as it was the first time so many exponents of these martial arts had gathered in the country. Since then, many of the practitioners who met there that day have shared this path.

Over the years, I participated in various activities organized in Caracas during Japan Cultural Week. In 2015, during an Aikido seminar, Mrs. Justina Soques, then a member of the embassy staff and also a practitioner, suggested bringing this event to the state of Aragua. Two days later, with the support of the Aragua Chamber of Commerce, Japan in Aragua was born, which was successfully held in 2016 and 2017. The large influx of people exceeded the capacity of the space, so, thanks to negotiations with the directors of San José School, whose facilities were more adequate, we were able to continue the event in the following years, both for the educational community and the general public.

Unfortunately, in February 2020, just before the start of a new edition, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the suspension of activities. After normalization, we decided to resume Japan in Aragua, an invaluable project for those of us who promote Japanese culture in Venezuela. We explored several options and, fortunately, found an enthusiastic ally in Casa de Italia de Maracay. Its board of directors was resolutely committed, and today the event is part of its annual program. It is a unique case, where three cultures come together: Italian, Japanese, and Venezuelan.

Currently, Japan in Aragua has a solid foundation, thanks to the institutional support of the Embassy of Japan, Casa de Italia de Maracay, the Bicentennial University of Aragua (UBA), and a renewed team that contributes fresh ideas. Since 2022, Casa de Italia de Maracay has held the event consecutively, consolidating its relevance in the region.

Receiving this recognition, which is being bestowed upon me today, is undoubtedly a source of great personal satisfaction and an honor for which I am deeply grateful. Since 2015, the various cultural attachés and assistants at the embassy, represented today by Patricia San and José San, have given me their trust and freedom of action. But beyond individual merit, this achievement is collective: we are a group of people who, over the years, have joined forces to share our dedication to Japanese culture. Therefore, I extend this recognition to all those who have been fundamental pillars of Japan in Aragua.

Today I'm joined by two indispensable people in this important part of my life: my son Miguelángel Pacheco, who has discreetly and efficiently managed the behind-the-scenes logistics, and lawyer Luís Suárez, my disciple for nearly 20 years and partner at Casa de Italia in Maracay, key to bringing the first edition to this new space. This award isn't just mine; it's a tribute to the deeds and shared effort that have brought us here.

I take this opportunity to invite you to reflect on how to expand Japan in Aragua to other states of Venezuela. Technology could be our ally, through workshops, conferences and online courses. As an example, I mention the experience we currently have at the Bicentennial University of Aragua, two years ago the UBA Dojo became a reality where Sensei Pascualino Sbraccia of Iaijutsu, Sensei Luis Reverón of karate and I have established an agreement with said university. Likewise, the Bicentennial University of Aragua has allocated a physical space in which various expressions of Japanese culture can be made known. There we could have, given the existing infrastructure, the possibility of developing experiences that allow us to set goals to project traditional Japanese culture and have over time an acceptable number of interested and actively participating people.

Once again, I thank Ambassador Yasushi Sato San, Cultural Attaché Keisuke Hasegawa San, and the entire embassy team for this invaluable experience. As the saying goes: "A person alone can achieve their goals, but accompanied they go further." Let us continue working together to reach new horizons.

|

|

Art. 3

Be the happy warrior

By Roxana Gramada,

4 dan Aikido Aikikai, Romania

It's not the dog in the fight, it's the fight in the dog. The thought comes to mind as I unpack one more bag after one more seminar. But wake me up at 3 AM and ask me why I go, and I'm not sure I have an answer. The week after, I am in emotional no man's land, my bones threatening to cut through my skin. Then along comes some pre-save-the-date Facebook post, and I am googling for flights. This is a drug, and I am a junkie.

Yet sometimes, most often during the Saturday morning class, I will skip a beat mid-technique, listening to the song of the mat. It's a living thing made of all of us. Have you ever heard it? And if you did, how do you not go again, as long as the knees allow it? Come to think of it, a few things could be in the way, especially if you're a woman. My recent four-year seminar binge gave me quite a tasting menu of those. And the writer in me (another addiction!) jumps at the story.

The “would you go alone?” test

Five years ago, I learned from some random Facebook post there was a summer camp in Belgium where Miyamoto sensei taught for a full week. And I immediately wanted to go. Just to see what happens when I give it a week. Not a weekend. A week. But nobody else would come. Because life. So I didn't. But then I had to live with the cost of doing nothing different. Which is that nothing different happens. Nothing. The next year, I packed a bag and went alone. I had been in several of sensei's seminars, so I thought, if I know nobody else, I know him. He looked at me and asked if this was my first seminar with him. It felt strangely liberating. Also, the Belgians have a reputation for good hosting. For good reason. Of all the places I've been, Spa is by far my favorite.

The “oh my God, Roxana, you're doing all the seminars!” sting

There's a compliment disguised there somewhere. I tell myself there is. After a few speechless rounds, I now say, “so do you, we keep running into each other.” Then I will say how there are times in my life when I can travel and times when I cannot. That's when a friend will generally appear. That's one of the upsides, by the way. Statistically, there will be on those mats people you will love with no further agenda, because they look like Kung Fu Panda, or crack up at the same jokes, or you can hear the click of ukemi falling into place with them. And you are glued the innocent way you made friends in kindergarten. And while you will never admit it under torture, to have that innocence again tears you up and gives you hope. Hide all you want. I know.

The “it's all because of your looks!” slap

I've had that said to me. By the powers that be. The friends I'd made, the things I'd learned and taught in my dojo and elsewhere, the doors I'd opened. They had, I was told, only one cause: how I look. First of all, thank you, in the name of all middle-aged, collagen-starved women out there, on the mat and beyond. But I can't help but wonder, would they say that to me if I were a man? I know a lot of good-looking, charismatic men on the mat. I don't suspect they have to put up with that. Here's a way to find out: if you're a man sensei out there reading this, please reply to this newsletter and inform the editor if that ever happened to you. Even better, please forward this to a man sensei you know and ask him if it ever happened to him. I would really love to know. And I would also love to know how they handled it. Irimi? Tenkan? Let's learn here. DM me.

The “yeah, it's just tourism!” cringe

As in, you going to the seminars is like you strolling through The Louvre or insert your museum of choice here. You didn't really learn anything. Is what they mean. First of all, thank you for the honesty. And while we're at it, are we swimming in nurturing, growth-oriented waters here? Second of all, here's some truth. The first time I went to - let's say Spa, since it's my favourite, I got hit by the stress train. Didn't really understand much. Came home in a trance and emailed my list of subscribers with what became one of my most-read ever emails (subject line: confessions of an almost top bitch). It took many seminars to be able to zoom in. Keep the kind of headspace where I can actually learn something. See details. Have some kind of progress. With more types of uke. The strong. The tiny. The more advanced. The kind. The star. The aloof. You get it. And then, after you think you have it, to go home and be able to pass something on. Years.

But I do have, after these trips, three rules I go by. 1. I am here to learn something. 2. I am here to be me, wherever my level may be. 3. I am here to give my uke the best I've got. So I just hold on to that and keep going. Because it is about the fight in the dog. But you know what, the fight in the dog better be a happy fight. We are, after all, happy warriors. And we're all in love with the same kind of magic.

|

|

Art. 4

Art. 5

Ne-waza in Aikido

By Gordon Hannah Shidoin

Dojo-cho of East End Aikikai, Pittsburgh, USA

Ne-waza means "ground techniques".

Aikido traditionally involves tachi-waza (standing techniques) and suwari-waza (kneeling techniques).

Ne-waza was not considered useful for furthering the broad vision of Aikido as a spiritual or self-improvement practice

and so was largely excluded from Aikido training.

Ne-waza is also not consistent with a self-defense posture which assumes a high likelihood of multiple and/or armed attackers.

Nevertheless, ne-waza is an important skill for those interested in the martial aspect of martial arts and is an aspect of

jiujitsu and judo training.

Kanai Sensei felt that the martial aspect of Aikido was essential to maintain in order to prevent Aikido from devolving into

a meaningless tradition of movement. He felt that the Aikido community needed to think more about ne-waza. In Kanai Sensei's

later years, he began teaching more sutemi waza (sacrifice throws) in which the nage "sacrifices" his balance in order to

throw the uke. Such techniques result in both uke and nage on the ground and, thus, suggests the need for ne-waza.

The various aspects of ne-waza include osae waza (pinning techniques), shime waza (choking techniques), and kansetsu waza

(joint locking techniques), and can, and in my opinion should, be explored within the Aikido curriculum in a manner consistent

with Aikido principles and etiquette.

|

|

Art. 6

Book Corner: Technical Aikido

By Mitsunari Kanai Shihan, 8th Dan

Chief Instructor of New England Aikikai (1966-2004)

Editor's note: In this "Book Corner" we provide installments of books relevant to our practice.

Following is Chapter 5 of Mitsunari Kanai Shihan's book "Technical Aikido".

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Complete)

Since we have published this Chapter in five parts, which leads to fragmentation and separation of related concepts, we publish it here in its entirety.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Part 1)

In this chapter, I will not address the complexity of defense in general; rather I will limit my discussion mainly to the relationship of Uke to Nage (the "other" or "partner") by focusing on how to fall and/or how to be thrown. Even in this limited examination, we must recognize several key issues.

First, one must understand the proper mental attitude appropriate to those who maintain and pursue the true form of "Bu" (martial arts). In developing the correct approach to ukemi, one must learn to master the ukemi techniques appropriate to any kind of waza (techniques) received from the Nage. This implies both receiving the full force of the Nage's technique, and also making the Nage's technique more refined or "polished".

Therefore one must understand these requirements while maintaining a serious attitude, as manifested in displaying correct manners to the Nage.

The following are simple descriptions of ukemi techniques; however, one must not forget that the basics of learning ukemi require one to practice executing all types of ukemi with a flexible body, a sharp mind, and an accurate judgment of the situation. Also it is essential to abandon an overly dependent relationship to the Nage; that is, a relationship based on a compromise of the principle that Uke and Nage are connected by a martial relationship.

There are several implications of this relationship. For example, Uke must not fall unless Nage's technique works. Also, Uke's technique must not depend on the assumption that the Nage will be kind, or that he will fail to exercise all his options, including kicking or striking the Uke if openings exist.

In training, one must polish one's own technique as well as the technique of one's partner, but at the same time one must maintain an attitude as serious and strict as if facing an enemy. This is the basis for a relationship that moves to higher levels based on a mutual commitment to polishing each partner's Aikido.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Part 2)

Koho Kaiten Ukemi (Back Roll ukemi)

The basic requirements of Koho Kaiten ukemi are to be able to take a back roll without hurting yourself when being thrown, and further, to always recognize that the most dangerous element in a martial situation is the person whom you are confronting.

You must practice with the understanding that the bottom line of Bujutsu (martial arts) is to protect yourself from the opponent(s) in any circumstances and at any point in time. This imposes certain technical requirements on the techniques of ukemi.

Failing to understand these requirements can create disastrous consequences for the current practice of Aikido. One can observe this in a commonly seen way to do Koho Kaiten ukemi.

In this case, the Uke begins his Koho Kaiten by stepping back with the inside leg (i.e. the leg closest to the Nage), bending the knee until the knee is touching the floor (in a kneeling posture). The Uke then puts the buttocks down on the mat and first, rolls backward and then rolls forward while touching the same knee on the mat and, finally, stands up.

Doing the backward roll in this way shows an insufficient awareness of the acute dangers inherent in performing all these movements directly in front of the opponent. What are these dangers?

First, you must realize that stepping back with the inside leg means you are exposed to a kick. Furthermore, to lower the inside knee to the ground after stepping back in this way shows a potentially fatal carelessness due to the exposure to a kick, and also to the loss of mobility inherent in this position.

The error of putting down the knee before falling is compounded, after falling, by rolling forward and standing up directly in front of the opponent. This is proof that one is acting independently of the opponent and is in a relationship diametrically opposite to the martial situation, where one is completely involved with the opponent, and where one's actions, to be correct, must acknowledge, and be based on, this interdependence. (The only exception is when practice is restricted by space limitations of a Dojo.) Rolling back while kneeling down and putting down the buttock in front of the other is a position exposing "Shini-Tai" (a "dead body" or "defenseless body") and, therefore, is a position in which you are unable to protect yourself.

As long as Nage or Uke base their approach to practice on an independent relationship with each other, the assumptions underlying their practice will not be consistent with the assumptions of a martial situation. Because Aikido, as a martial art, is based on these (and other) assumptions, one cannot ignore them without compromising its essential nature. Nonetheless, many people have done exactly this, and are practicing an adulterated form which should not be called Aikido because it has been drained of its essential character as a martial art. Approached from such a perspective, Aikido becomes reduced to a barren play, in which one can never produce or grasp anything from the real Aikido.

Therefore, when taking ukemi, do not step back with the leg which is closest to the other! And, do not put down the knee when falling!

What then is the correct way to take Koho Kaiten ukemi? Basically, you must take a big step back with the outside leg and bend that knee without folding the foot so that the bottom of the foot continues to touch the mat. Then put down the same side buttock and do Koho Kaiten by rolling back over the inside shoulder, and then, after rolling over, stand up in Hanmi, take Ma-Ai and face the other.

Depending on the particular technique received from the Nage, it can be appropriate to roll back over the outside shoulder (while still stepping back with the outside leg).

In any event, to perform such correct ukemi, you must utilize the elastic power of the legs sufficiently. In Aikido, the "elastic power" (or "bending and stretching power") is a basic method utilized to produce power or to soften power received from an opponent. In the case of backward ukemi, for example, only by using the elastic power of the back leg after the back roll, can you create the momentum for standing up.

You must use the Achilles' tendon and the hamstring muscle (as well as all other muscles and tendons below' the hip) as a part of creating power when you are being thrown, just as you use them when you are throwing.

Zenpo Kaiten Ukemi (Front Roll Ukemi)

Step forward with the outside leg, i.e. the leg which is further away from the Nage. If, for example, the right leg is the outside leg, extend the right arm forward while pointing its fingers inward and curve the right arm. Then make the outside of the curved arm touch the mat smoothly and roll your entire body forward through, in order, the right shoulder, the curved back, and the left hip.

To complete the roll and rise to standing position, fold the left knee and position the right knee in a bent but upright position. Upon arriving at this one knee kneeling position, by using the momentum of the rolling, put your weight on the ball of the right foot and do Tenkan at the same time standing up and positioning yourself at Migi Hanmi to prepare for the next move. Complete the movement by taking a sufficient Ma-Ai which prepares for the next move of the opponent. Therefore, when one practices this Zenpo Kaiten movement the goal should be to make it low and far (i.e. lower in height and further in distance).

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Part 3)

Mae-ukemi (Break Fall) No.1

Step forward with the outside leg that is, the leg further away from the Nage (in this case the right leg). Spring with this leg as the pivot and do Zenpo Kaiten in the air. When landing on the mat, separate the body and arm so as to make a 45-degree angle between them and hit the floor first with the left arm in order to soften the impact on the rest of the body.

Then hit the mat simultaneously with the entire stretched left leg and the sole of the right foot and (the right instep and right knee are bent). At the instant the left leg and the right sole land on the mat, the upper body must be bent forward. (By this time, the elbow of the left arm, which hit the mat, must have already been bent and the left hand must have already supported the rising upper body.) Bending the upper body in this way is necessary to protect the internal organs from the impact.

It is important to keep the legs spread apart sufficiently because if the right knee cannot withstand the momentum generated by the impact and as a result collapses to the inside, the inside of the right knee must not hit the left leg.

Immediately after the left leg and the right foot land on the mat, using the momentum generated by the movement, twist the hip back to the right, and while standing up using the right knee as a pivot, do Tenkan with the left foot as the pivot and assume a Hidari Hanmi stance in order to be prepared for any move of the opponent.

Depending on which Nage waza (Throwing Technique) is employed, Zenpo Kaiten ukemi (Front Roll) may not be sufficient, and this is the ukemi which, in such a case, is necessary to protect one's self. It is like Zenpo Kaiten in some respects, but is different in others. You must learn the differences.

Train so that you can manage to do this ukemi flexibly when being thrown to the front, back, left or right.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Part 4)

Mae-ukemi (Break Fall) No.2

This ukemi should be used when being thrown directly down by techniques such as Koshi Nage or Kata Guruma, and it is almost the same as Mae-ukemi No. 1. In case of taking ukemi on the left side of the body, land on the mat with the left arm, left leg and the right foot sole simultaneously, while lifting the back (from the left abdomen to the left armpit) from the mat to protect the internal organs. Also, pull the chin forward to prevent the head from striking the mat. Both the angle of the arm and body as they hit the mat, and the distance between both legs are the same as the previous Mae-ukemi. Train very thoroughly because one receives a very strong impact when taking this ukemi.

Both of the Mae-ukemi waza are ukemi waza based on uniting oneself instantaneously with the body of the opponent who initiated the waza by making one point of body contact the pivot point. The pivot point is that point on the Uke's body where Nage's power is most loaded (or placed) onto the Uke, or, conversely, the point of Nage's body where Uke's weight is most loaded onto the Nage.

The pivot point can move (within a range) in the course of a technique, but at all times it is the point of strongest contact between the Uke and Nage. Therefore, one needs to clearly understand which part of the opponent's body (the part which the opponent's power is directly put on) one must utilize for this purpose. The point of contact is generally the shoulder, elbow, or hip.

When one is thrown in the air, one must put one's body in the correct position in order to land safely. However, while one is in the air and not in contact with any object, it is difficult to move in any way, much less move accurately. Therefore, one must use the reactionary power of the throw itself, received through one point of contact with the opponent's body (usually shoulder, elbow, or hip), to provide sufficient force to propel one to a position where one's orientation is regained.

This happens in one instant, so Uke must rapidly and accurately determine which part of Nage's body he will use.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Part 5)

Sokuto (Yoko-ukemi)

This ukemi should be used when being thrown down on one's side by Ashi Barai (Leg Sweep) or Okuri Iriminage.

In case of Hidari Hanmi (which would be the case if the left foot were the outside foot, i.e. the foot further away from the Nage), a moment before the left side of the body lands on the mat, one must hit the mat quickly with the stretched left arm, which is extended away from the body (maintaining an approximately 20 degree angle between the body and the arm), and shift the body's position so that the part of the body that lands first is the left part of the hip, and the part of the body that lands later is the upper left of the body. The instant the left hip lands on the mat, stretch both legs and kick them upward (twisting to the right front side of the body). This movement controls the balance of the body and prevents the left side of the body from receiving an abrupt and injurious impact.

Much training is required in order to hit the mat quickly and strongly with the extended arm, because in this case, one arm alone absorbs nearly all the impact received by the entire body.

The way of standing up is the same with Ma-ukemi.

There are also other ukemi such as Zenpo (Front Fall) or Koho (Back Fall) which are done when rolling is not possible due to insufficient space or other physical limitations. I would like to explain about these in the future.

It is necessary that one know when and how to do all types of ukemi. Just as Nage is required absolutely to make a posture based on the principle of reactionary power, Uke also must do ukemi based on the principle of reactionary power.

In other words, one must make sufficient use of the sources of reactionary power, which results from putting power on anything that has weight. For example, reactionary power would include the Nage's power, a part of the body, and the mat. Thus one can control one's own body. Unless one understands this principle, ukemi as practiced will never be the true ukemi.

You must practice until you are convinced that even when the power of an opponent is imposed on you with maximum force, if you can use the opponent's body in the correct way, you will be able to take the safest and most correct ukemi.

When one is being thrown, the power of the other is always imposed on a particular part of one's body. One must do ukemi either by utilizing the power which is imposed on oneself as the reactionary power, or by using the contact point between the other and oneself as a source for reactionary power.

Therefore, do not start your ukemi by "jumping" rashly in advance of the Nage's throw. Do not decide which to do, Ma or Kaiten-ukemi, before being thrown. Adapt oneself to the circumstances instantaneously and let the Nage's technique determine which you take. This approach must be thought through carefully and then consistently applied to practice.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Complete)

(this goes above)Since we have published this Chapter in five parts, which leads to fragmentation and separation of related concepts,

we publish it here in its entirety.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI

In this chapter, I will not address the complexity of defense in general; rather I will limit my discussion mainly to the relationship of Uke to Nage (the "other" or "partner") by focusing on how to fall and/or how to be thrown. Even in this limited examination, we must recognize several key issues.

First, one must understand the proper mental attitude appropriate to those who maintain and pursue the true form of "Bu" (martial arts). In developing the correct approach to ukemi, one must learn to master the ukemi techniques appropriate to any kind of waza (techniques) received from the Nage. This implies both receiving the full force of the Nage's technique, and also making the Nage's technique more refined or "polished".

Therefore one must understand these requirements while maintaining a serious attitude, as manifested in displaying correct manners to the Nage.

The following are simple descriptions of ukemi techniques; however, one must not forget that the basics of learning ukemi require one to practice executing all types of ukemi with a flexible body, a sharp mind, and an accurate judgment of the situation. Also it is essential to abandon an overly dependent relationship to the Nage; that is, a relationship based on a compromise of the principle that Uke and Nage are connected by a martial relationship.

There are several implications of this relationship. For example, Uke must not fall unless Nage's technique works. Also, Uke's technique must not depend on the assumption that the Nage will be kind, or that he will fail to exercise all his options, including kicking or striking the Uke if openings exist.

In training, one must polish one's own technique as well as the technique of one's partner, but at the same time one must maintain an attitude as serious and strict as if facing an enemy. This is the basis for a relationship that moves to higher levels based on a mutual commitment to polishing each partner's Aikido.

Koho Kaiten Ukemi (Back Roll ukemi)

The basic requirements of Koho Kaiten ukemi are to be able to take a back roll without hurting yourself when being thrown, and further, to always recognize that the most dangerous element in a martial situation is the person whom you are confronting.

You must practice with the understanding that the bottom line of Bujutsu (martial arts) is to protect yourself from the opponent(s) in any circumstances and at any point in time. This imposes certain technical requirements on the techniques of ukemi.

Failing to understand these requirements can create disastrous consequences for the current practice of Aikido. One can observe this in a commonly seen way to do Koho Kaiten ukemi.

In this case, the Uke begins his Koho Kaiten by stepping back with the inside leg (i.e. the leg closest to the Nage), bending the knee until the knee is touching the floor (in a kneeling posture). The Uke then puts the buttocks down on the mat and first, rolls backward and then rolls forward while touching the same knee on the mat and, finally, stands up.

Doing the backward roll in this way shows an insufficient awareness of the acute dangers inherent in performing all these movements directly in front of the opponent. What are these dangers?

First, you must realize that stepping back with the inside leg means you are exposed to a kick. Furthermore, to lower the inside knee to the ground after stepping back in this way shows a potentially fatal carelessness due to the exposure to a kick, and also to the loss of mobility inherent in this position.

The error of putting down the knee before falling is compounded, after falling, by rolling forward and standing up directly in front of the opponent. This is proof that one is acting independently of the opponent and is in a relationship diametrically opposite to the martial situation, where one is completely involved with the opponent, and where one's actions, to be correct, must acknowledge, and be based on, this interdependence. (The only exception is when practice is restricted by space limitations of a Dojo.) Rolling back while kneeling down and putting down the buttock in front of the other is a position exposing "Shini-Tai" (a "dead body" or "defenseless body") and, therefore, is a position in which you are unable to protect yourself.

As long as Nage or Uke base their approach to practice on an independent relationship with each other, the assumptions underlying their practice will not be consistent with the assumptions of a martial situation. Because Aikido, as a martial art, is based on these (and other) assumptions, one cannot ignore them without compromising its essential nature. Nonetheless, many people have done exactly this, and are practicing an adulterated form which should not be called Aikido because it has been drained of its essential character as a martial art. Approached from such a perspective, Aikido becomes reduced to a barren play, in which one can never produce or grasp anything from the real Aikido.

Therefore, when taking ukemi, do not step back with the leg which is closest to the other! And, do not put down the knee when falling!

What then is the correct way to take Koho Kaiten ukemi? Basically, you must take a big step back with the outside leg and bend that knee without folding the foot so that the bottom of the foot continues to touch the mat. Then put down the same side buttock and do Koho Kaiten by rolling back over the inside shoulder, and then, after rolling over, stand up in Hanmi, take Ma-Ai and face the other.

Depending on the particular technique received from the Nage, it can be appropriate to roll back over the outside shoulder (while still stepping back with the outside leg).

In any event, to perform such correct ukemi, you must utilize the elastic power of the legs sufficiently. In Aikido, the "elastic power" (or "bending and stretching power") is a basic method utilized to produce power or to soften power received from an opponent. In the case of backward ukemi, for example, only by using the elastic power of the back leg after the back roll, can you create the momentum for standing up.

You must use the Achilles' tendon and the hamstring muscle (as well as all other muscles and tendons below' the hip) as a part of creating power when you are being thrown, just as you use them when you are throwing.

Zenpo Kaiten Ukemi (Front Roll Ukemi)

Step forward with the outside leg, i.e. the leg which is further away from the Nage. If, for example, the right leg is the outside leg, extend the right arm forward while pointing its fingers inward and curve the right arm. Then make the outside of the curved arm touch the mat smoothly and roll your entire body forward through, in order, the right shoulder, the curved back, and the left hip.

To complete the roll and rise to standing position, fold the left knee and position the right knee in a bent but upright position. Upon arriving at this one knee kneeling position, by using the momentum of the rolling, put your weight on the ball of the right foot and do Tenkan at the same time standing up and positioning yourself at Migi Hanmi to prepare for the next move. Complete the movement by taking a sufficient Ma-Ai which prepares for the next move of the opponent. Therefore, when one practices this Zenpo Kaiten movement the goal should be to make it low and far (i.e. lower in height and further in distance).

Mae-ukemi (Break Fall) No.1

Step forward with the outside leg that is, the leg further away from the Nage (in this case the right leg). Spring with this leg as the pivot and do Zenpo Kaiten in the air. When landing on the mat, separate the body and arm so as to make a 45-degree angle between them and hit the floor first with the left arm in order to soften the impact on the rest of the body.

Then hit the mat simultaneously with the entire stretched left leg and the sole of the right foot and (the right instep and right knee are bent). At the instant the left leg and the right sole land on the mat, the upper body must be bent forward. (By this time, the elbow of the left arm, which hit the mat, must have already been bent and the left hand must have already supported the rising upper body.) Bending the upper body in this way is necessary to protect the internal organs from the impact.

It is important to keep the legs spread apart sufficiently because if the right knee cannot withstand the momentum generated by the impact and as a result collapses to the inside, the inside of the right knee must not hit the left leg.

Immediately after the left leg and the right foot land on the mat, using the momentum generated by the movement, twist the hip back to the right, and while standing up using the right knee as a pivot, do Tenkan with the left foot as the pivot and assume a Hidari Hanmi stance in order to be prepared for any move of the opponent.

Depending on which Nage waza (Throwing Technique) is employed, Zenpo Kaiten ukemi (Front Roll) may not be sufficient, and this is the ukemi which, in such a case, is necessary to protect one's self. It is like Zenpo Kaiten in some respects, but is different in others. You must learn the differences.

Train so that you can manage to do this ukemi flexibly when being thrown to the front, back, left or right.

Mae-ukemi (Break Fall) No.2

This ukemi should be used when being thrown directly down by techniques such as Koshi Nage or Kata Guruma, and it is almost the same as Mae-ukemi No. 1. In case of taking ukemi on the left side of the body, land on the mat with the left arm, left leg and the right foot sole simultaneously, while lifting the back (from the left abdomen to the left armpit) from the mat to protect the internal organs. Also, pull the chin forward to prevent the head from striking the mat. Both the angle of the arm and body as they hit the mat, and the distance between both legs are the same as the previous Mae-ukemi. Train very thoroughly because one receives a very strong impact when taking this ukemi.

Both of the Mae-ukemi waza are ukemi waza based on uniting oneself instantaneously with the body of the opponent who initiated the waza by making one point of body contact the pivot point. The pivot point is that point on the Uke's body where Nage's power is most loaded (or placed) onto the Uke, or, conversely, the point of Nage's body where Uke's weight is most loaded onto the Nage.

The pivot point can move (within a range) in the course of a technique, but at all times it is the point of strongest contact between the Uke and Nage. Therefore, one needs to clearly understand which part of the opponent's body (the part which the opponent's power is directly put on) one must utilize for this purpose. The point of contact is generally the shoulder, elbow, or hip.

When one is thrown in the air, one must put one's body in the correct position in order to land safely. However, while one is in the air and not in contact with any object, it is difficult to move in any way, much less move accurately. Therefore, one must use the reactionary power of the throw itself, received through one point of contact with the opponent's body (usually shoulder, elbow, or hip), to provide sufficient force to propel one to a position where one's orientation is regained.

This happens in one instant, so Uke must rapidly and accurately determine which part of Nage's body he will use.

Sokuto (Yoko-ukemi)

This ukemi should be used when being thrown down on one's side by Ashi Barai (Leg Sweep) or Okuri Iriminage.

In case of Hidari Hanmi (which would be the case if the left foot were the outside foot, i.e. the foot further away from the Nage), a moment before the left side of the body lands on the mat, one must hit the mat quickly with the stretched left arm, which is extended away from the body (maintaining an approximately 20 degree angle between the body and the arm), and shift the body's position so that the part of the body that lands first is the left part of the hip, and the part of the body that lands later is the upper left of the body. The instant the left hip lands on the mat, stretch both legs and kick them upward (twisting to the right front side of the body). This movement controls the balance of the body and prevents the left side of the body from receiving an abrupt and injurious impact.

Much training is required in order to hit the mat quickly and strongly with the extended arm, because in this case, one arm alone absorbs nearly all the impact received by the entire body.

The way of standing up is the same with Ma-ukemi.

There are also other ukemi such as Zenpo (Front Fall) or Koho (Back Fall) which are done when rolling is not possible due to insufficient space or other physical limitations. I would like to explain about these in the future.

It is necessary that one know when and how to do all types of ukemi. Just as Nage is required absolutely to make a posture based on the principle of reactionary power, Uke also must do ukemi based on the principle of reactionary power.

In other words, one must make sufficient use of the sources of reactionary power, which results from putting power on anything that has weight. For example, reactionary power would include the Nage's power, a part of the body, and the mat. Thus one can control one's own body. Unless one understands this principle, ukemi as practiced will never be the true ukemi.

You must practice until you are convinced that even when the power of an opponent is imposed on you with maximum force, if you can use the opponent's body in the correct way, you will be able to take the safest and most correct ukemi.

When one is being thrown, the power of the other is always imposed on a particular part of one's body. One must do ukemi either by utilizing the power which is imposed on oneself as the reactionary power, or by using the contact point between the other and oneself as a source for reactionary power.

Therefore, do not start your ukemi by "jumping" rashly in advance of the Nage's throw. Do not decide which to do, Ma or Kaiten-ukemi, before being thrown. Adapt oneself to the circumstances instantaneously and let the Nage's technique determine which you take. This approach must be thought through carefully and then consistently applied to practice.

Technical Aikido © Mitsunari Kanai 1994-96

|

|

Comics

Comics - Aikido Animals: The Blocker

By Jutta Bossert

The Blocker

They block everything you do,

unless you do it exactly the way they think is right

– which doesn’t necessarily have anything to do

with what Sensei is teaching.

© Jutta Bossert - Used by permission.

|

|

Art. 8

Fishing without bait

By Enrique Silvera

Technical Director, Asociación Samurai Aikido Kawai, Uruguay

Schools should pay attention to the way some people act.

Typically, these are aikidoists who, throughout their career, have never had a dojo or people under their care,

because they generally have a complicated background and a lack of martial codes.

How do they act?

They look for lower-rank students who are members of a dojo. They call them and ask to visit and practice.

After class, they try to entice them with invitations to join a group, claiming to work in a unique style.

This makes the student feel honored by the invitation.

This student may not be aware that accepting the invitation could cause complications for the rest of his classmates

at the school he attends.

It is okay for them to visit other schools, after notifying their teacher, because it may be out of friendship.

Our school's protocol is to allow training at other schools, always keeping in mind the goal of remaining faithful

to Hombu Dojo, Shin Kaze, and ASAK.

Participation in training at any other dojo, as well as seminars from other organizations, may only be done with

Sensei's consent.

Someone who fishes without bait wants to poach students without having a dojo, teacher, or institutional responsibility.

|

|

Art. 9

Dojos granted Provisional Member status

We are pleased to announce that the following dojos have been granted Provisional Member status:

- Santiago del Estero Aikikai Dojo, located in the city of Santiago del Estero, Argentina, led by dojo-cho Leandro Ernesto Obligado, godan.

- Kyiv Aikido Club, located in the city of Kyiv, Ukraine, led by dojo-cho Mykola Yemelianov, sandan.

Welcome!

|

|

Art. 10

My history in Aikido

By Leandro Obligado

Dojo-cho, Santiago del Estero Aikikai, Argentina

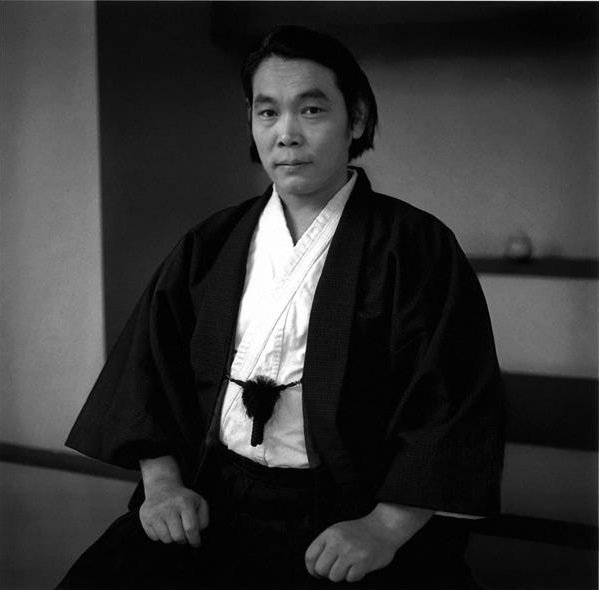

Picture: Leandro with Sensei Juan Tolone, when he graduated to shodan.

I began my Aikido practice in 1991, in the city of Córdoba, under the guidance of Sensei Daniel Lucero.

There, I took my first steps in this martial art, with dedication and perseverance, discovering on the tatami not only

a technical system, but also a path of life.

After almost a decade of training, in July 1999, I took my 1st Dan exam at Buenos Aires Aikikai - Aikido Foundation Argentina,

chaired by Sensei Juan Tolone and Ricardo Corbal. The exam was administered by Sensei Yoshimitsu Yamada Shihan, a world leader

in Aikido, which marked an unforgettable milestone in my training.

In September 1999, I settled in the city of Santiago del Estero, where the Santiago del Estero Aikikai was born. I was the

first 1st Dan to arrive in the province, beginning to spread and teach Aikido under the technical direction of Sensei Juan Tolone.

From there, I began a path that united personal practice with teaching and community building.

The year 2000 marked a leap in my training: I participated in international seminars organized by the Aikido Argentina Foundation,

where I had the opportunity to train with teachers such as Claude Bertiaume Shihan, Donovan Waite Shihan, Peter Bernath Shihan,

and Yoshimitsu Yamada Shihan. That same year, I traveled to the United States to attend the NEA East Coast Summer Camp, where

I shared the tatami with teachers and aikidoists from all over the world. It was the true beginning of my international journey,

understanding that Aikido is a universal language.

In 2004, I attended the 40th Anniversary of the NY Aikikai in New York, a historic event where I was able to train with

Doshu Moriteru Ueshiba, Nobuyoshi Tamura, and Yoshimitsu Yamada, among others. It was an encounter that left an indelible mark

on my practice and my life.

Over the years, I was fortunate to receive instruction from great masters such as Donovan Waite Shihan, Christian Tissier Shihan,

Claude Bertiaume Shihan, Peter Bernath Shihan, Bruno González Sensei, Yoko Okamoto Sensei, Juan Tolone Shihan, and Robert

Zimmermann Shihan, among many others. Each seminar not only provided me with technical knowledge, but also human and spiritual

experiences that enriched my vision of Aikido.

A special chapter was my role as organizer of international seminars in Santiago del Estero and Termas de Río Hondo,

hosting Donovan Waite Shihan and Sensei Robert Zimmermann. These international events, held in my province,

were a source of personal and collective pride, as they brought world-class teachers to our region and projected the

local community into the international arena.

In 2014, I traveled to Canada to participate in Yoshimitsu Yamada Shihan's 50th Anniversary, held at Aikido de la Montagne

(Montreal), where the career of one of the great pillars of Aikido in the West was recognized.

In 2016, I had the opportunity to travel to Japan and attend the 12th IAF Congress in Takasaki. It was a unique experience:

training in the birthplace of Aikido, surrounded by aikidoka from all over the world, confirmed the universality and strength

of this art.

In recent years, I have continued to maintain an active practice. In 2022, I participated in Shihan Juan Tolone's seminar

in La Pampa, and in 2025 in Shihan Robert Zimmermann's seminar in Córdoba, always with the same motivation as in my first days

in Córdoba in 1991.

A difficult stage

My path also had challenges. For a period of three years, we were without direct affiliation, during which we organized

national seminars with teachers such as Sensei Nico Coll and Sensei Julio Farías, strengthening the practice in the region.

However, many of these seminars could not be recorded because my Yudansha Book (Aikido passport) was retained in La Pampa.

Despite multiple requests, it was not returned to me, and I was only able to recover it several years later. This left a void in

official records, but not in practice: activities continued, the dojo grew, and the community was sustained with commitment.

In December 2022, I formally left the Aikido Argentina Foundation, marking the end of one stage and the beginning of another,

with institutional independence, but with the same commitment as always to the practice and dissemination of Aikido.

Balance

Today, looking back, I recognize a journey of more than thirty years of practice (1991-2025), with 25 years of uninterrupted

participation in national and international seminars. I also proudly carry the satisfaction of having been the first Dan to

bring Aikido to Santiago del Estero, of having organized international events in my province, and of having overcome difficult

times without ever losing the continuity of my practice.

My history in Aikido cannot be understood without my family. Throughout this entire journey, I was accompanied by my wife Lidia,

who was always by my side, encouraging, supporting, and giving me the strength to continue. With her, we formed a beautiful

family, along with our three children: Juan Cruz, Valentina, and Agustín. They, along with Lidia, have been the support and

inspiration that allowed me to fully dedicate myself to Aikido, and I owe them everything I have been able to achieve.

My story in Aikido is not just a succession of training sessions and travels: it is a life story, made up of effort, encounters,

overcome obstacles, and learning.

Because in reality, I didn't practice Aikido in my life: I made my life with Aikido.

|

|

Art. 11

Memories of a tatami, spirit of a dojo

By Leandro Obligado, Dojo-cho, and Aldo Heredia, Sandan

Santiago del Estero Aikikai, Argentina

Author's Note:

This is the story of our dojo.

It is told as if the dojo and its tatami were recounting their experiences.

We have tried to give the article a title that reflects the spirit of this story.

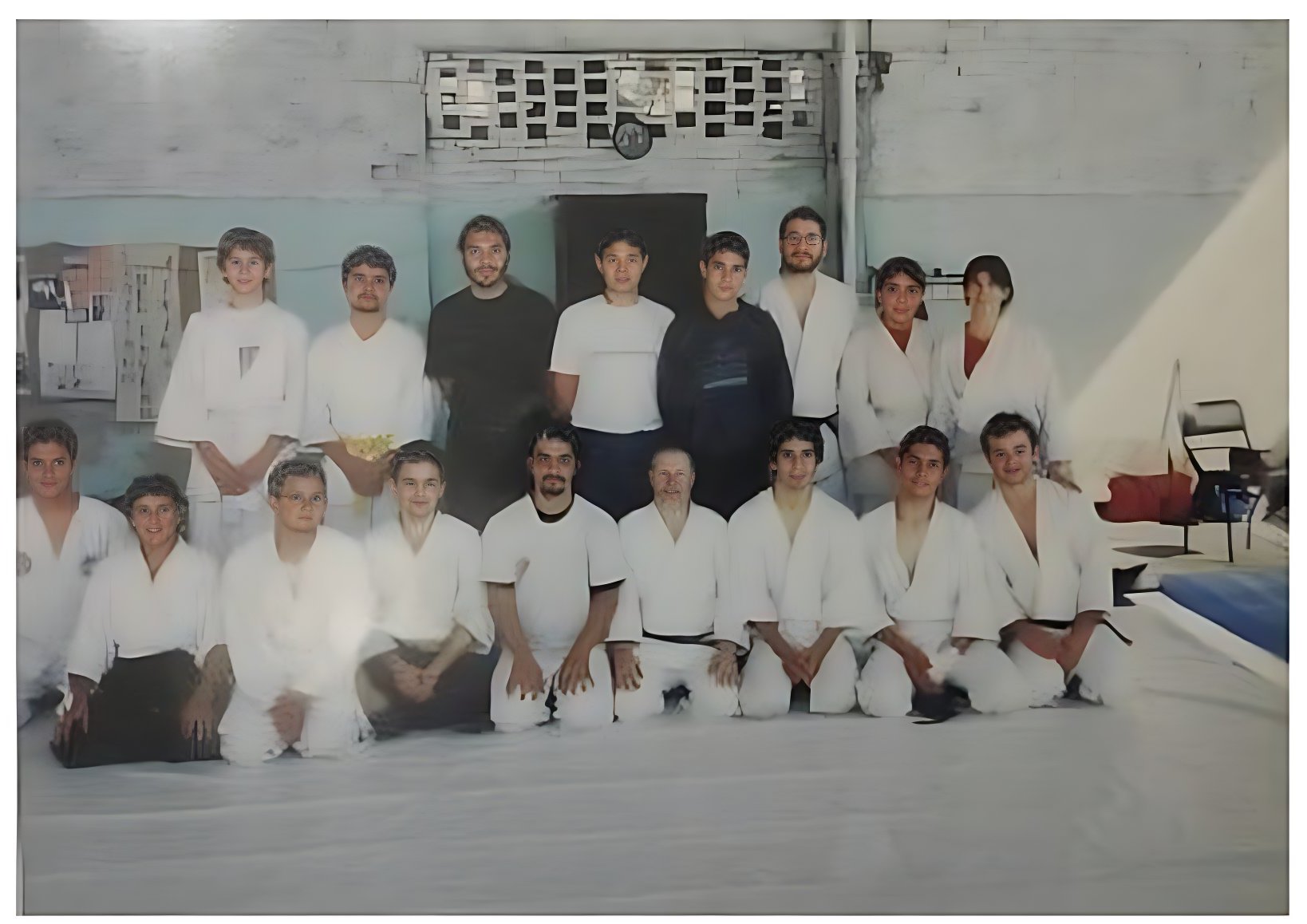

Picture: Iguana dojo.

I was born at a time when tatami mats didn't yet exist. When Sensei Leandro Obligado returned to live in Santiago del Estero, we began to take our first steps. My first practices were humble: just four rubber mats, spread out in a small room at the Syrian-Lebanese Society. There weren't enough funds for anything bigger, and what we had was simple, modest, almost improvised. But it was enough.

At that time, Sensei had just earned his first Dan, in July of that same year. He came with little experience teaching classes, but with all the passion and dedication necessary to sow the seed of what would later become a true dojo. Very soon, a group of teenagers and young students began to follow him. They trained with enthusiasm, with energy, with that overflowing passion of the beginning. Today, looking back, I discover that many of those youthful faces, almost unrecognizable in old photos, transformed over the years into black belts, instructors, and group leaders. It was they who, from that early stage of youth, helped give me strength and continuity, turning the small beginning into a living community.

Then came other spaces. One of the most memorable was the back of the Iguana Gym. There, with a tin roof and a large window that opened to the street, people trained in stifling heat. Jokingly, they called it Iwama, like the legendary Japanese dojo, but over time it earned another, more powerful nickname: the dojo of hell. That nickname originated in Santiago, when instructors and practitioners from Buenos Aires and other provinces came to share classes and suffered the extreme heat and intensity of the practice. They said it in a sarcastic and mischievous tone, but with recognition: training in Santiago was training in the dojo of hell.

At Iguana, a custom was also born that stayed with me forever. The space was multipurpose and was used for other activities, so we had to clean before and after each class, and set up and take down the tatami. If the students didn't arrive in time to set it up, practice would start anyway, on the floor, with the tatami left leaning against the wall, watching. And I, the tatami, laughed silently watching them perform their ukemi on the hard floor, although deep down I cared for them just the same. Thus, a teaching was forged that became my trademark: practice doesn't begin with the greeting, but much earlier, in the care of the tatami and the shared space. That custom of cleaning, setting up, and taking down stayed with me always, no matter where I was.

Later, I moved to the Italian Society, where I continued with a larger, albeit shared, space, and then to a Güemes Club location on the corner of Güemes and Colón. There, the custom of setting up and taking down the tatami continued, reinforcing discipline, respect, and affection for the practice. Then came the Casa de Italia on San Martín Street, a larger space but always shared with other activities. There, the habit of cleaning before and after each class was maintained. It wasn't an obligation; it was a duty born of affection for the dojo, the tatami, and those who inhabited it.

Over time, I stopped being a nomad. I built my permanent home in the Cabildo neighborhood of Santiago del Estero. There, I finally had a permanent tatami mat — Olympic mats — a practice buki, furniture, and everything I needed to train with dedication. That space represented roots, permanence, identity. I no longer had to set up and take down the mats every day, nor share schedules with anyone: it was finally a complete dojo, always open to practice.

During that stage, I truly grew. Black belts, instructors, and group leaders emerged. Those young people who started with me, with almost adolescent faces, transformed into leaders and teachers in their own right. And it was also here that a phrase was adopted that became the motto of my tatami: "Visitors welcome". Sensei brought it back from one of his trips, inspired by another dojo where he had trained. From then on, we have embraced it as our own: a tatami open to the world, ready to welcome all practitioners, regardless of their origin, creed, race, or religion.

It was with that spirit that I received great masters. Shihan Tolone, Shihan Ricardo Corbal, Shihan Donovan Waite, and Shihan Robert Zimmermann walked over me, and I silently retain the vibration of their footsteps and their teachings. I remember those multitudinous seminars, with people from all over, where extra tatami mats had to be added because there wasn't enough space. I stretched myself beyond my limits, and in those days I felt like a beating heart, charged with the energy of masters and students training together passionately.

I also welcomed practitioners from other provinces and countries like Perú, Chile, and Venezuela. In every case, I experienced the same feeling: my tatami opened up to them, confirming that the motto "visitors welcome" was not an empty phrase, but a living practice.

And I have a special mention for Shihan Tolone, who always offered love and instruction in each of his practices with me. I, the tatami, felt his particular warmth in every step and in every technique, a deep affection for the practitioners and for the dojo of Santiago del Estero. Even in those times of the so-called dojo of hell, his energy left a distinct mark: that of a master who, in addition to teaching, knew how to transmit closeness and heart.

But it wasn't all joy. I also cried. Because a tatami doesn't just hold footprints and ukemi: it holds stories, laughter, silences, affection. And one day I had to say goodbye to a son, a brother born to me: Omar René “Cacho” Maldonado, Nidan. Cacho was a fundamental pillar, a constant support, and a great friend. His death, after a harsh and cruel illness, wasn't just a pain for me: we all suffered it. A few days before his departure, he himself asked to return to practice. We went to look for him, and a video of that last time still exists. That day he didn't come to train: he came to say goodbye to me. He hugged me, and in that hug, he let a tear fall onto my surface. I picked it up and still hold it in silence, as I hold all the memories that gave me life. That tear was his last signal, his way of saying goodbye.

His absence left an immense void, but his presence also remains: in every greeting, in every ukemi, in every memory. I still embrace him like a son who never truly leaves.

Today, with all those memories, I am part of the neighborhood. I don't have any signs or posters outside that say "Aikido." But if anyone asks, any neighbor's answer is simple: "The dojo is on the corner of Filas and 24th Street." And in the neighborhood, everyone knows that "24th Street" refers to 24th of September Street. That's how they recognize me: without signs, without advertisements, just for being there, fulfilling not only a function in Aikido, but also a social and cultural role, a meeting place, a place for friends and community.

I am Santiago del Estero Aikikai. I am the tatami that holds the memory of those who came, those who are here, and those who have gone. I am the place where Aikido took root, and where there will always be an open space for all who wish to enter.

I am also a place where people and leaders are formed. Here, values of respect, commitment, and human integrity are transmitted. Because each ukemi on my surface not only builds Aikido practitioners: it builds stronger, more integral human beings, more capable of guiding others with humility and heart.

|

|

Art. 12

Kyiv Aikido Club

By Mykola Yemelianov

Dojo-cho, Kyiv Aikido Club, Kyiv, Ukraine

About the dojo

Brothers Mykola and Oleksandr Yemelianov began practicing Aikido in 2005 and later began training students.

Olena Suvorova began practicing Aikido in 2016 under the instruction of Mykola Yemelianov. In April 2019,

Mykola, Oleksandr and Olena founded Kyiv Aikido Club.

Kyiv Aikido Club is a public organization whose main goal is to develop and popularize Aikikai Aikido based

on the principles established by its founder, Morihei Ueshiba. The instructors strive to teach Aikido at a

highly professional level, conducting intensive training in a friendly and respectful atmosphere.

In 2019, training was held in one dojo, and in August 2022, the club's second dojo opened. During the Covid-19

pandemic, the club was closed for only two and a half months (from mid-March to the end of May), and when

the invasion began, the break in training lasted only 5 months (March-July). So, despite all the difficulties,

Kyiv Aikido Club is operating and growing.

Currently, about 100 students (children, teenagers and adults) train daily and kyu examinations take place every

six months. Sensei and students regularly attend seminars taught by prominent Aikido masters in Ukraine and abroad.

The club regularly organizes Aiki-festivals for children, takes children to summer Aiki-camps to train, and holds

away Aiki-weekends for adults.

About the main instructor

Mykola Yemelianov began training at the Ukrainian Aikido Federation in Kyiv in 2005 under the instruction of Sensei

Serhiy Nedilko (Shodan from Toshiro Suga Shihan). In 2016 he began training under the instruction of Sensei

Mikhailo Korozey (Yondan from Robert Zimmermann Shihan).

Since 2016, Mykola has been working as an instructor for children, teenagers and adults. In 2019, together with his

colleagues, he founded Kyiv Aikido Club which he currently heads.

Mykola received shodan in 2016 and nidan in 2018 from Toshiro Suga Shihan. He received sandan in 2024 from Mikhailo

Korozey Shidoin. He has attended seminars instructed by such masters as Robert Zimmermann Shihan, Toshiro Suga Shihan,

Stephane Benedetti Shihan, Takanori Kuribayashi Shihan, and many others.

Currently, Mykola continues to train and study under Mykhailo Korozey Shidoin, and conducts training for children,

teenagers, and adults.

|

|

Art. 13

Reporting Aikido Injuries

Safety in Aikido practice is paramount, and a systematic approach to safe practice should always be observed

to minimize occurrence of injuries. However, even with the best of intentions and practices, injuries do occur

at times in Aikido, as in any martial art or physical activity.

To keep a record, identify and correct unsafe practices in Shin Kaze, a database was set up in mid-2022

for dojo-cho to record injuries as reported to them by their students. Fortunately no injuries have been

reported to date, but this may be because the dojo-cho were not informed. To streamline the reporting process

and make it more widely available, as of October 2023 all Shin Kaze members can report injuries anonymously.

To report an injury first log in to the Shin Kaze web site or register as a new user. Once logged in click on

the ADMIN tab on the top menu and then on the "Injury Report" tab on the left hand side. The "Aikido

Injury Report Form" will be displayed on the right and you will be able to create an injury report.

Hopefully there will be no injuries and there will be minimal use of this database.

|

|

Art. 14

Art. 15

Art. 16

Art. 17

Dear Dojo-cho and Supporters:

Please distribute this newsletter to your dojo members, friends and anyone interested in

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance.

If you would like to receive this newsletter directly, click

here.

|

|

|

|

SUGGESTION BOX

Do you have a great idea or suggestion?

We want to hear all about it!

Click

here

to send it to us.

|

Donations

In these difficult times and as a nonprofit organization, Shin Kaze welcomes donations to support

its programs and further its mission.

Please donate here:

https://shinkazeaikidoalliance.com/support/

We would also like to mention that we accept gifts of stock as well as bequests to help us build

our Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance endowment.

Thank you for your support!

|

|

|

|

|

|