Comments

Header

News from Shin Kaze

July 2025

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance is an organization dedicated to the practice and development of

Aikido. It aims to provide technical and administrative guidance to Aikido practitioners and

to maintain standards of practice and instruction within an egalitarian and tolerant structure.

|

|

Table of Contents

Introduction

Introduction

Greetings and a hearty welcome to the July 2025 edition of the Shin Kaze newsletter, showcasing the rich tapestry of

our global community and their unique perspectives.

In this issue we present a fascinating exploration of ego in Aikido practice;

a collection of vibrant reports detailing recent seminars and the personal experiences of their attendees;

presentations of new dojos that have joined Shin Kaze with provisional membership, including an article about

one of these dojos;

the final segment of the Book Corner, which continues Kanai Sensei's book "Technical Aikido" with the third section

of Chapter 5 on ukemi;

and the final part of a thought-provoking essay examining Aikido's search for relevance in today's world.

We invite you to delve into this issue and hope it inspires you to share your own stories in future editions.

Happy reading!

|

|

Art. 2

And what is the ego, the one they talk so much about?

By

Maria Paz Santillan

Almost 2nd kyu, Kokoro Dojo, Córdoba, Argentina

We have heard it many times, in classes and in good talks after classes, that the work of Aikido is, among other things,

work on the ego and a competition with oneself. We've heard it as something natural, oh, by the way. We heard it

those days when after training, we recognize that, at the same time we learned something and thought, "I got it!",

now new doubts appear, and the field wxpands further to study and practice. That is, in those days when you

realize that you know less than you think, or in other words, you experience that as you learn more, the more you

see all that remains to be learned. As if one managed to open a door, entered, and saw that inside there were many

more doors, all the way to infinity.

The classic situation of any Tuesday: two hours of Shomenuchi Ikkyo knowing that not once did you get it "right",

and knowing that there is no other way, because there really is no other way, than to continue practicing for many

long years so that one day yo almost perform the technique correctly;

knowing that there is no other choice but to be patient with oneself, to listen carefully, humbly and with admiration for

your teacher and your fellow practitioners, some of higher rank and others of lower rank, but all of them always teaching

something; falling down and getting up again and again, without complaining or hurrying or punishing oneself,

accepting one's shortcomings and celebrating one's achievements as well as those of our practice partners ...

and, throughout, engage in a thankfulness exercise, thanking countless times in the same class, at the beginning O-Sensei

and your teacher, and then every practice partner, among many other emotions and sensations of Aikido.

But then, where is the ego? What is the ego?

What does it mean when someone has an ego that is "too big", or "an elevated ego"?

You've heard this, haven't you?

What does one think of one of your own ego?

Is my ego elevated and I have to lower it?

Or is it too low, and I have to raise it?

Does it change as days go by, or is it always the same?

What can I do to find out?

Does Aikido really help me with this? How?

Searching the internet, I found some definitions of the “ego” that I would like to share with you so we can think together:

Sigmund Freud (1853 -1939): “The ego is responsible for balancing internal needs with the demands of the outside world.”

For Freud, the ego acts as a mediator between our unconscious desires, social norms, and reality. Its function is to find the best possible way to satisfy what we feel, without endangering ourselves or coming into conflict with our environment.

Eckhart Tolle (1948 - present): “The ego lives completely identified with form, and its identity depends on that form.”

For Tolle, the ego is built from identification with one's own thoughts, personal history, achievements, failures, and the roles we occupy.

Osho (1931 - 1990): “The ego is nothing more than a shadow. If you look at it, it disappears.”

Osho points out that the ego is not a real substance, but an illusion fueled by fear and separation.

Buda (Dhammapada): “He who conquers the ego, conquers the world.”

In Buddhism, the ego is associated with attachment and the illusion of separation from the universe, and dissolving it leads to awakening.

Chat GPT: “The ego is, in essence, the image that each person has of themselves."

It's not a bad thing: we all need a sense of identity to move through the world. The ego helps you say: “I am so-and-so, I like such-and-such, I practice Aikido, I have dreams.”

As you can see, there are as many definitions as there are people, and we could say, broadly speaking, that everything

revolves around the same thing: one's own, one's internal self, right? That which only one knows and feels, deep within

one's heart, one's Kokoro, often without the possibility of expressing it in words or outwardly, but one knows that it

is there, that it exists and speaks.

And what can we say now, with what we've read? Well, not much. Rather, new questions arise, as we've always said when

one learns something. (Thank God, because that's what life is about.)

What then is it, to be egocentric in everyday life?

What is it to be egocentric on the Tatami?

If today I am egocentric and want something different, what can I do to change it?

Continuing with the idea of giving shape to what we understand by “ego”, perhaps to recognize its place in us, we can

continue with the word itself, the semantics:

The word egocentrism comes from Latin:

● ego = self

● centrum = center

● ism = suffix indicating doctrine, tendency or behavior

So, egocentrism literally means: “The tendency to place the self at the center of all things.”

We could say then that egocentrism is a way of interpreting reality in which everything revolves around the self,

one's own perceptions, needs, opinions, tastes, or desires. That is, the highly egocentric person cannot

(or does not want to) see the world from any point of view other than their own; they do not think of anyone but

themselves, do not consider the problems or needs of others, and only suffer for themselves.

Jean Piaget, a Swiss biologist, spoke of infantile egocentrism to describe how, in the early stages of development,

young children do not yet distinguish between their own point of view and that of others. It's not selfishness;

they simply have not yet developed the ability to listen to themselves. Interesting, isn't it?

Should we be a little more childish, or should we learn, as adults, that our point of view isn't the only valid one,

and that our problems aren't the only important ones? Maybe this is a good answer. Problem solved? I don't think so.

So where does Aikido fit into all this? You know, many answers can arise from that question, and what a joy that there

are so many. Personally, I don't have any clear conclusions. At this moment, as I find myself in the middle of my exam process,

about to take 2nd kyu very soon, I can tell you that the current experience is confronting me with nothing more and nothing less

than myself (or my ego?) and the difficult task of seeing or hearing precisely the way I've thought about myself all my life,

my own memories and fears, my passions, my own hopes and ideas about the future, pillars that fall or disappear and new pillars

that are forming. I am confronted with how I see how others see me. I am confronted with how I defended myself, perhaps with

some hints of regret that appear, which, by redirecting them (or trying to), invite me to rethink the present,

and how I want to defend myself today. If there's no competition with others, and I'm competing with myself, where's the tournament?

On that random Tuesday? Yes, probably there. On that ordinary, forgettable day, where you don't even know what date it is,

where nothing goes as expected, where the internal and external world feels like chaos, where everything is dizzying,

where wars exist and your salary isn't enough, there, where you face nothing more and nothing less than your own hands and your own heart,

where all that remains is the present time and space, you can no longer leap to the past or the future with your mind;

the mind can and only wants to be here today, and ultimately, tomorrow. So the big question that finally arises is:

if what I'm doing is Aikido, and what I'm facing is my ego, can I step out of the line of my own attacks? Can I step out of the line

of my own fears? Can I redirect my own—self-centered—energy toward something positive, peaceful, and do it calmly? If what I'm

facing is this ego, this other self, can I look at it directly and tell it not to compete with me, just practice? Can I thank it

for the practice, even when the exercise didn't work out, or was difficult? Well, not so much... but yes.

To go a little deeper and put things into practice, I looked up some interesting mental exercises on the internet:

Exercise 1. Imagine the ego.

Give visual form to what you feel. Don't try to think of "something nice." Imagine what your ego looks like today:

Is it very big? Is it dark or light? Is it a shadow? Does it have a mask? Is it a child? A monster? A rock star?

Ask yourself: Do I want to yell at this person, protect it, or applaud it?

Exercise 2: Reconnecting with our younger ego.

If you saw yourself as a 5-year-old boy or girl, what would you say? Would you take care of him or her?

There's a great connection to the ego, to our most essential self. Perhaps we can try speaking to our ego as if it

were that helpless child, not an enemy adult, and in that way redirect the negative energy.

Exercise 3: Thank it.

Practice accepting your ego as a friend, not an enemy. Some night before going to sleep, thank it (and yourself)

for the day's progress, the practice, and the learning, including the mistakes you made—and yes, the big ones too.

I once heard a father ask his children every Sunday at dinner: "And this week, what were your mistakes?" If they said they

hadn't made any mistakes, it didn't count; it wasn't true. They had to count at least three, and they had to try to count

them with joy, enthusiasm, and a constructive air. This way, they could practice seeing their own "mistakes" in a healthy way,

without denying them or getting upset about them. It makes you want to try, doesn't it?

So what do we do with all this? What is the ego? The truth is, I still don't know. In every class, our Sensei reminds us

not to clash, but to always move forward with the best energy, step out of line and take cover, find our safe place, and

then redirect without brute force or hurting our partner. Perhaps then, from this point of view, we can think that what we

have with our ego isn't a confrontation, but rather an encounter, where we look into each other's eyes, without hurting each

other, giving each other space and being grateful.

Perhaps it's not about "never thinking about yourself" or "thinking only about yourself," but rather about thinking respectfully

and with balance about others and yourself. Whenever possible, care for and help good friends, loved ones, family, and fellow

practitioners, but without forgetting that there is one's own desire and one's own life, because beyond everything,

the only person who will live our life is, ultimately, ourselves.

So, what is the ego? It seems it's no longer so important to define it, but simply to learn to live with it. Yes, like a

good practice partner.

|

|

Art. 3

Aikido seminar in Santa Clara, Cuba

By Fiona Blyth Shidoin

Dojo-cho The Wind on the Top of the Mountain, UK

I feel very lucky to have been able to attend the seminar instructed by Robert Zimmermann Shihan this past Spring in the city of Santa Clara, the capital city of the province of Villa Clara, Cuba. Those days are etched in my memory: the people, the dojo, the Aikido practice, the camaraderie, the food, the beautiful colours and most of all everyone’s kindness and attentiveness. It was indeed a beautiful seminar, held in an airy municipal gymnasium full of light, organized by Leonel Sánchez Sotolongo Sensei, dojo-cho and main instructor of Kan Sho Ryu Dojo in the municipality of Cifuentes in Villa Clara.

A bunch of students from Toronto Aikikai and I flew from Toronto to Santa Clara, where we were picked up at the airport by Leonel Sensei after waiting a while, as Elizabeth (later to become my dear roommate ..!) somehow ended up in the longest line to come through the security check, due to the electricity going off and on as our luggage slowly made its way through the only available scanner. Whilst we waited I became acquainted with a small brown and white spaniel called Jalal, a drug sniffing dog. His owner and trainer was a soldier working at customs. The airport was welcoming and there was a feeling of calm and delight when passengers were picked up by their friends or families.

We arrived at our lodging, a small family hotel with colours of blue and earthen brick, run by a delightful family. Immediately we were asked if we were hungry and fresh fruit juice appeared, and a brunch with eggs and fruit and toast and delicious coffee was served. We ate breakfast and lunch on the rooftop patio and relaxed in rocking chairs looking at the mango trees and flowers, soothed by a light breeze.

Aikido classes started the day we arrived! After a short rest (some of us napped..!) we were ready to go. Waiting outside our residence was the taxi which was to take us all to the gymnasium where the seminar would be held. The taxi was rather unusual, a small open chariot with a green canvas awning (see the picture), pulled by motorcycle with the word TAXI on the front under the handlebars. All eight of us were happily crowded and perched on wooden benches in the back and jostled our way around bumps in the road up the hill to the gymnasium, admiring the scenery, a cacophony of colours and smells, flowers and trees and the occasional horse and cart - all the while with a wind gently blowing through the open seating of our taxi.

Once we arrived at the gymnasium, we walked up the stairs to a municipal sports hall, which was stunning. A large, open space full of natural light, with bleachers. The air was fresh, and the hall was well ventilated, with a breeze blowing through from the open window slats above. The Cuban students had laid out the tatami in the middle of the large space with the Kamiza carefully set up at the front. We could see how much care and effort had gone into arranging the practice area.

During our first day of Aikido, Robert Zimmermann Sensei said he would start with some basics. However, what he introduced as a ‘working on the basics’ class, quickly transitioned into maki otoshi from shomen uchi…The energy this generated was a wakeup call and we were all delighted and leapt right in!

We had classes on Friday, Saturday and Sunday, and we trained with different people in each class, learning and working together ignoring language and cultural barriers. The enthusiasm and welcoming spirit from the Cuban students were heartwarming. Some had traveled for several hours to get to the seminar, and all were so pleased to be there. Many stayed in the gymnasium so they could be there all weekend and attend every class.

We were supplied with bananas and water between classes and everything was perfect.

Tests were held after classes on Saturday, and Isis, Leonel Sensei’s 14 year old daughter did a wonderful 3rd kyu test, followed by other higher kyu level tests and dan tests to shodan by Cuban students and to sandan by students from Venezuela and Spain. Congratulations to all who took their tests and passed.

I wish to thank all the Cuban Aikido students who made such an effort to attend the seminar, Leonel Sensei for welcoming us so kindly and generously, and Robert Sensei for his incredible instruction, attention to detail, patience and warm heart to all of us! Moreover, I wish to thank both Leonel Sensei and Robert Sensei for creating this invaluable connection and friendship between different countries and cultures.

This was in every way a weekend I will never forget and one I very much wish will be repeated, with even more people joining from many countries and in this way form international bonds leading to closer connection, friendship and understanding.

I look forward to the next seminar in Cuba in April 2026 and hope you will come and join us!

|

|

Art. 4

The Tatami as a mirror

By Luis Suárez, Sandan

Aikido Kokyu Ho Dojo, Maracay, Venezuela

“Success is going from failure to failure, without losing enthusiasm.”

Winston Churchill

I would like to share some lessons from Aikido that have helped me progress. These come from reflections on my experiences

at the International Seminar in Santa Clara, Cuba, that took place from 4 to 6 April 2025.

I feel that the lived experience has vibrant considerations, which cannot go unnoticed, and that, as a treasure found

after a long journey, I share as the echo of what I have lived and that resonated in every technique, sweat and silence

with Shihan Robert Zimmermann and the Cuban delegation during such a positive seminar.

The unexpected as a starting point

Seven months ago, this meeting in Cuba was unthinkable, not even a vague desire. During the weekend of October 4-6, 2024,

after many years, we had the opportunity to share a seminar in Venezuela with Shihan Robert Zimmermann; an activity that,

despite local difficulties, we were able to accomplish with satisfaction, rekindling in us the motivation to pursue his

teachings.

Thus, Jovani Lobo and I set a new goal for ourselves: to travel to coincide with the Shihan and thus further our martial

training. What seemed like a scattered idea became a tangible goal that moved us to firmly organize ourselves.

We were then able to accomplish the unexpected: we traveled to participate in the seminar under a feeling of euphoria,

carrying in our keikogi the spirit of our organization: Venezuela Aikido Kokyu Ho Dojo. Every throw, every fall,

every suburi, every technical exchange was marked with a "we." Cuba didn't host two practitioners, but an entire community

embodied on the tatami.

Infinite gratitude to Sensei Rafael Pacheco, whose unwavering commitment transformed a wish into a feat. Likewise, I must

thank Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance and Sensei Leonel Sánchez, along with his group in Cuba, for giving us the opportunity to

enjoy such a special seminar.

Barriers are mirrors

Dojo-cho Leonel Sánchez and his students confronted me with an uncomfortable truth:

"It's not the headwind, but the sails we don't hoist." — Paulo Coelho.

Their practice, sometimes with limited resources, are examples of resilience. While elsewhere we complain about what's

missing,they created Aikido with the essential: pure passion.

How many times have we used excuses — time, money, conditions — to justify our mediocrity? Aikido isn't just on the mat;

it's in the mind of those who choose to practice it. We are a reflection of what we set out to do, a mirror of the barriers

we overcome, both within and without.

Humility as a Master Weapon

What was technically admirable in Cuba wasn't perfection, but the thirst for improvement.

Practitioners joyfully questioned their own ways, as if carving their spirit with a chisel of authenticity.

Improvement was the criterion, evolution the mission. When was the last time we examined ourselves with such brutal honesty?

As Mandela said: "It is not he who is without fear who is brave, but he who conquers fear."

I perceived that they trained with a fear of stagnating, not of falling. We, on the other hand, are we afraid of the effort

that liberates us? Being cautious about what we know, open and humble to what is invited and taught to us, striving to

improve ourselves, that I believe is the goal.

The flight home (and inward)

I returned home with a sweaty gi and a lighter soul.

I reaffirm what I clearly thought: Aikido is like bamboo; it can bend, but it never breaks.

Our true Dojo lies in the will we carry within us, because despite fatigue or difficulty,

it's enough to return to the foundations that led us to take this path with integrity to move forward.

The journey, as trite as it may sound, is not the destination. The journey is the direction we take, the journey along the path,

the vicissitudes we face, the laughter we find, the stumbles we overcome, the many times we get back on our feet.

And to assimilate all of this, Aikido is the instrument.

"¡Arigato!" — Thanks to you, to Cuba, and to the adversities that taught us to fly.

See you on the tatami... or wherever we decide to practice life with Aikido.

|

|

Art. 5

The first International Seminar of the Kokoro Dojo Martial Arts Center

By

Maria Paz Santillan

Kokoro Dojo, Córdoba, Argentina

On May 10 and 11, in Córdoba's capital city, we lived an unforgettable experience. The Kokoro Dojo Martial Arts Center organized its first International Seminar with Shihan Roberto Zimmermann. For many it was their first seminar; for others, one more step along the way. For everyone, however, it was an unprecedented weekend, with great gratitude for the practice and classes shared.

The sunny climate accompanied wonderfully, and between talks with a good mate (a traditional South American caffeine-rich infused herbal drink) we were able to learn Aikido both off and on the mat, thanks to the humility and generosity of teachers Roberto Zimmermann Shihan and Daniel Medina Shidoin, who gave of their time with attention and care to each of those present.

We practiced contact, with the other and with our hands. We practice silence and listening, attention and respect. Listening, patience, presence. We talked about our history, about our doubts and our whys. From the past, of the future, of the present. We talked about life, time, loyalty. About perseverance in oneself and in practice. About falling and getting up, about mistakes and successes. We talked about the ego, the world, and although it seems incredible, everything found its place in Aikido: we took those same questions to the mat, where the body began to rehearse possible answers, and with the body and the spirit, we responded little by little.

We also witnessed, with great emotion, the Dan exams of students who, for years, have given their heart - Kokoro - to practice and to the school, helping to build this space among all, and making the school a place where you can grow up well accompanied.

We learned that the mind must be a beginner's mind in order to learn. That the body should not lose contact. That it needs connection. That it is always possible to find a space to take care of ourselves, a safe place. And the only way to keep on learning is to keep on practicing.

We are deeply grateful for Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance's disposition and company, for making this encounter possible and for strengthening the bonds of shared practice.

Thank you so much!

|

|

Art. 6

Book Corner: Technical Aikido

By Mitsunari Kanai Shihan, 8th Dan

Chief Instructor of New England Aikikai (1966-2004)

Editor's note: In this "Book Corner" we provide installments of books relevant to our practice.

Following is Chapter 5 of Mitsunari Kanai Shihan's book "Technical Aikido".

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Complete)

Since we have published this Chapter in five parts, which leads to fragmentation and separation of related concepts, we publish it here in its entirety.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Part 1)

In this chapter, I will not address the complexity of defense in general; rather I will limit my discussion mainly to the relationship of Uke to Nage (the "other" or "partner") by focusing on how to fall and/or how to be thrown. Even in this limited examination, we must recognize several key issues.

First, one must understand the proper mental attitude appropriate to those who maintain and pursue the true form of "Bu" (martial arts). In developing the correct approach to ukemi, one must learn to master the ukemi techniques appropriate to any kind of waza (techniques) received from the Nage. This implies both receiving the full force of the Nage's technique, and also making the Nage's technique more refined or "polished".

Therefore one must understand these requirements while maintaining a serious attitude, as manifested in displaying correct manners to the Nage.

The following are simple descriptions of ukemi techniques; however, one must not forget that the basics of learning ukemi require one to practice executing all types of ukemi with a flexible body, a sharp mind, and an accurate judgment of the situation. Also it is essential to abandon an overly dependent relationship to the Nage; that is, a relationship based on a compromise of the principle that Uke and Nage are connected by a martial relationship.

There are several implications of this relationship. For example, Uke must not fall unless Nage's technique works. Also, Uke's technique must not depend on the assumption that the Nage will be kind, or that he will fail to exercise all his options, including kicking or striking the Uke if openings exist.

In training, one must polish one's own technique as well as the technique of one's partner, but at the same time one must maintain an attitude as serious and strict as if facing an enemy. This is the basis for a relationship that moves to higher levels based on a mutual commitment to polishing each partner's Aikido.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Part 2)

Koho Kaiten Ukemi (Back Roll ukemi)

The basic requirements of Koho Kaiten ukemi are to be able to take a back roll without hurting yourself when being thrown, and further, to always recognize that the most dangerous element in a martial situation is the person whom you are confronting.

You must practice with the understanding that the bottom line of Bujutsu (martial arts) is to protect yourself from the opponent(s) in any circumstances and at any point in time. This imposes certain technical requirements on the techniques of ukemi.

Failing to understand these requirements can create disastrous consequences for the current practice of Aikido. One can observe this in a commonly seen way to do Koho Kaiten ukemi.

In this case, the Uke begins his Koho Kaiten by stepping back with the inside leg (i.e. the leg closest to the Nage), bending the knee until the knee is touching the floor (in a kneeling posture). The Uke then puts the buttocks down on the mat and first, rolls backward and then rolls forward while touching the same knee on the mat and, finally, stands up.

Doing the backward roll in this way shows an insufficient awareness of the acute dangers inherent in performing all these movements directly in front of the opponent. What are these dangers?

First, you must realize that stepping back with the inside leg means you are exposed to a kick. Furthermore, to lower the inside knee to the ground after stepping back in this way shows a potentially fatal carelessness due to the exposure to a kick, and also to the loss of mobility inherent in this position.

The error of putting down the knee before falling is compounded, after falling, by rolling forward and standing up directly in front of the opponent. This is proof that one is acting independently of the opponent and is in a relationship diametrically opposite to the martial situation, where one is completely involved with the opponent, and where one's actions, to be correct, must acknowledge, and be based on, this interdependence. (The only exception is when practice is restricted by space limitations of a Dojo.) Rolling back while kneeling down and putting down the buttock in front of the other is a position exposing "Shini-Tai" (a "dead body" or "defenseless body") and, therefore, is a position in which you are unable to protect yourself.

As long as Nage or Uke base their approach to practice on an independent relationship with each other, the assumptions underlying their practice will not be consistent with the assumptions of a martial situation. Because Aikido, as a martial art, is based on these (and other) assumptions, one cannot ignore them without compromising its essential nature. Nonetheless, many people have done exactly this, and are practicing an adulterated form which should not be called Aikido because it has been drained of its essential character as a martial art. Approached from such a perspective, Aikido becomes reduced to a barren play, in which one can never produce or grasp anything from the real Aikido.

Therefore, when taking ukemi, do not step back with the leg which is closest to the other! And, do not put down the knee when falling!

What then is the correct way to take Koho Kaiten ukemi? Basically, you must take a big step back with the outside leg and bend that knee without folding the foot so that the bottom of the foot continues to touch the mat. Then put down the same side buttock and do Koho Kaiten by rolling back over the inside shoulder, and then, after rolling over, stand up in Hanmi, take Ma-Ai and face the other.

Depending on the particular technique received from the Nage, it can be appropriate to roll back over the outside shoulder (while still stepping back with the outside leg).

In any event, to perform such correct ukemi, you must utilize the elastic power of the legs sufficiently. In Aikido, the "elastic power" (or "bending and stretching power") is a basic method utilized to produce power or to soften power received from an opponent. In the case of backward ukemi, for example, only by using the elastic power of the back leg after the back roll, can you create the momentum for standing up.

You must use the Achilles' tendon and the hamstring muscle (as well as all other muscles and tendons below' the hip) as a part of creating power when you are being thrown, just as you use them when you are throwing.

Zenpo Kaiten Ukemi (Front Roll Ukemi)

Step forward with the outside leg, i.e. the leg which is further away from the Nage. If, for example, the right leg is the outside leg, extend the right arm forward while pointing its fingers inward and curve the right arm. Then make the outside of the curved arm touch the mat smoothly and roll your entire body forward through, in order, the right shoulder, the curved back, and the left hip.

To complete the roll and rise to standing position, fold the left knee and position the right knee in a bent but upright position. Upon arriving at this one knee kneeling position, by using the momentum of the rolling, put your weight on the ball of the right foot and do Tenkan at the same time standing up and positioning yourself at Migi Hanmi to prepare for the next move. Complete the movement by taking a sufficient Ma-Ai which prepares for the next move of the opponent. Therefore, when one practices this Zenpo Kaiten movement the goal should be to make it low and far (i.e. lower in height and further in distance).

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Part 3)

Mae-ukemi (Break Fall) No.1

Step forward with the outside leg that is, the leg further away from the Nage (in this case the right leg). Spring with this leg as the pivot and do Zenpo Kaiten in the air. When landing on the mat, separate the body and arm so as to make a 45-degree angle between them and hit the floor first with the left arm in order to soften the impact on the rest of the body.

Then hit the mat simultaneously with the entire stretched left leg and the sole of the right foot and (the right instep and right knee are bent). At the instant the left leg and the right sole land on the mat, the upper body must be bent forward. (By this time, the elbow of the left arm, which hit the mat, must have already been bent and the left hand must have already supported the rising upper body.) Bending the upper body in this way is necessary to protect the internal organs from the impact.

It is important to keep the legs spread apart sufficiently because if the right knee cannot withstand the momentum generated by the impact and as a result collapses to the inside, the inside of the right knee must not hit the left leg.

Immediately after the left leg and the right foot land on the mat, using the momentum generated by the movement, twist the hip back to the right, and while standing up using the right knee as a pivot, do Tenkan with the left foot as the pivot and assume a Hidari Hanmi stance in order to be prepared for any move of the opponent.

Depending on which Nage waza (Throwing Technique) is employed, Zenpo Kaiten ukemi (Front Roll) may not be sufficient, and this is the ukemi which, in such a case, is necessary to protect one's self. It is like Zenpo Kaiten in some respects, but is different in others. You must learn the differences.

Train so that you can manage to do this ukemi flexibly when being thrown to the front, back, left or right.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Part 4)

Mae-ukemi (Break Fall) No.2

This ukemi should be used when being thrown directly down by techniques such as Koshi Nage or Kata Guruma, and it is almost the same as Mae-ukemi No. 1. In case of taking ukemi on the left side of the body, land on the mat with the left arm, left leg and the right foot sole simultaneously, while lifting the back (from the left abdomen to the left armpit) from the mat to protect the internal organs. Also, pull the chin forward to prevent the head from striking the mat. Both the angle of the arm and body as they hit the mat, and the distance between both legs are the same as the previous Mae-ukemi. Train very thoroughly because one receives a very strong impact when taking this ukemi.

Both of the Mae-ukemi waza are ukemi waza based on uniting oneself instantaneously with the body of the opponent who initiated the waza by making one point of body contact the pivot point. The pivot point is that point on the Uke's body where Nage's power is most loaded (or placed) onto the Uke, or, conversely, the point of Nage's body where Uke's weight is most loaded onto the Nage.

The pivot point can move (within a range) in the course of a technique, but at all times it is the point of strongest contact between the Uke and Nage. Therefore, one needs to clearly understand which part of the opponent's body (the part which the opponent's power is directly put on) one must utilize for this purpose. The point of contact is generally the shoulder, elbow, or hip.

When one is thrown in the air, one must put one's body in the correct position in order to land safely. However, while one is in the air and not in contact with any object, it is difficult to move in any way, much less move accurately. Therefore, one must use the reactionary power of the throw itself, received through one point of contact with the opponent's body (usually shoulder, elbow, or hip), to provide sufficient force to propel one to a position where one's orientation is regained.

This happens in one instant, so Uke must rapidly and accurately determine which part of Nage's body he will use.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Part 5)

Sokuto (Yoko-ukemi)

This ukemi should be used when being thrown down on one's side by Ashi Barai (Leg Sweep) or Okuri Iriminage.

In case of Hidari Hanmi (which would be the case if the left foot were the outside foot, i.e. the foot further away from the Nage), a moment before the left side of the body lands on the mat, one must hit the mat quickly with the stretched left arm, which is extended away from the body (maintaining an approximately 20 degree angle between the body and the arm), and shift the body's position so that the part of the body that lands first is the left part of the hip, and the part of the body that lands later is the upper left of the body. The instant the left hip lands on the mat, stretch both legs and kick them upward (twisting to the right front side of the body). This movement controls the balance of the body and prevents the left side of the body from receiving an abrupt and injurious impact.

Much training is required in order to hit the mat quickly and strongly with the extended arm, because in this case, one arm alone absorbs nearly all the impact received by the entire body.

The way of standing up is the same with Ma-ukemi.

There are also other ukemi such as Zenpo (Front Fall) or Koho (Back Fall) which are done when rolling is not possible due to insufficient space or other physical limitations. I would like to explain about these in the future.

It is necessary that one know when and how to do all types of ukemi. Just as Nage is required absolutely to make a posture based on the principle of reactionary power, Uke also must do ukemi based on the principle of reactionary power.

In other words, one must make sufficient use of the sources of reactionary power, which results from putting power on anything that has weight. For example, reactionary power would include the Nage's power, a part of the body, and the mat. Thus one can control one's own body. Unless one understands this principle, ukemi as practiced will never be the true ukemi.

You must practice until you are convinced that even when the power of an opponent is imposed on you with maximum force, if you can use the opponent's body in the correct way, you will be able to take the safest and most correct ukemi.

When one is being thrown, the power of the other is always imposed on a particular part of one's body. One must do ukemi either by utilizing the power which is imposed on oneself as the reactionary power, or by using the contact point between the other and oneself as a source for reactionary power.

Therefore, do not start your ukemi by "jumping" rashly in advance of the Nage's throw. Do not decide which to do, Ma or Kaiten-ukemi, before being thrown. Adapt oneself to the circumstances instantaneously and let the Nage's technique determine which you take. This approach must be thought through carefully and then consistently applied to practice.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Complete)

(this goes above)Since we have published this Chapter in five parts, which leads to fragmentation and separation of related concepts,

we publish it here in its entirety.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI

In this chapter, I will not address the complexity of defense in general; rather I will limit my discussion mainly to the relationship of Uke to Nage (the "other" or "partner") by focusing on how to fall and/or how to be thrown. Even in this limited examination, we must recognize several key issues.

First, one must understand the proper mental attitude appropriate to those who maintain and pursue the true form of "Bu" (martial arts). In developing the correct approach to ukemi, one must learn to master the ukemi techniques appropriate to any kind of waza (techniques) received from the Nage. This implies both receiving the full force of the Nage's technique, and also making the Nage's technique more refined or "polished".

Therefore one must understand these requirements while maintaining a serious attitude, as manifested in displaying correct manners to the Nage.

The following are simple descriptions of ukemi techniques; however, one must not forget that the basics of learning ukemi require one to practice executing all types of ukemi with a flexible body, a sharp mind, and an accurate judgment of the situation. Also it is essential to abandon an overly dependent relationship to the Nage; that is, a relationship based on a compromise of the principle that Uke and Nage are connected by a martial relationship.

There are several implications of this relationship. For example, Uke must not fall unless Nage's technique works. Also, Uke's technique must not depend on the assumption that the Nage will be kind, or that he will fail to exercise all his options, including kicking or striking the Uke if openings exist.

In training, one must polish one's own technique as well as the technique of one's partner, but at the same time one must maintain an attitude as serious and strict as if facing an enemy. This is the basis for a relationship that moves to higher levels based on a mutual commitment to polishing each partner's Aikido.

Koho Kaiten Ukemi (Back Roll ukemi)

The basic requirements of Koho Kaiten ukemi are to be able to take a back roll without hurting yourself when being thrown, and further, to always recognize that the most dangerous element in a martial situation is the person whom you are confronting.

You must practice with the understanding that the bottom line of Bujutsu (martial arts) is to protect yourself from the opponent(s) in any circumstances and at any point in time. This imposes certain technical requirements on the techniques of ukemi.

Failing to understand these requirements can create disastrous consequences for the current practice of Aikido. One can observe this in a commonly seen way to do Koho Kaiten ukemi.

In this case, the Uke begins his Koho Kaiten by stepping back with the inside leg (i.e. the leg closest to the Nage), bending the knee until the knee is touching the floor (in a kneeling posture). The Uke then puts the buttocks down on the mat and first, rolls backward and then rolls forward while touching the same knee on the mat and, finally, stands up.

Doing the backward roll in this way shows an insufficient awareness of the acute dangers inherent in performing all these movements directly in front of the opponent. What are these dangers?

First, you must realize that stepping back with the inside leg means you are exposed to a kick. Furthermore, to lower the inside knee to the ground after stepping back in this way shows a potentially fatal carelessness due to the exposure to a kick, and also to the loss of mobility inherent in this position.

The error of putting down the knee before falling is compounded, after falling, by rolling forward and standing up directly in front of the opponent. This is proof that one is acting independently of the opponent and is in a relationship diametrically opposite to the martial situation, where one is completely involved with the opponent, and where one's actions, to be correct, must acknowledge, and be based on, this interdependence. (The only exception is when practice is restricted by space limitations of a Dojo.) Rolling back while kneeling down and putting down the buttock in front of the other is a position exposing "Shini-Tai" (a "dead body" or "defenseless body") and, therefore, is a position in which you are unable to protect yourself.

As long as Nage or Uke base their approach to practice on an independent relationship with each other, the assumptions underlying their practice will not be consistent with the assumptions of a martial situation. Because Aikido, as a martial art, is based on these (and other) assumptions, one cannot ignore them without compromising its essential nature. Nonetheless, many people have done exactly this, and are practicing an adulterated form which should not be called Aikido because it has been drained of its essential character as a martial art. Approached from such a perspective, Aikido becomes reduced to a barren play, in which one can never produce or grasp anything from the real Aikido.

Therefore, when taking ukemi, do not step back with the leg which is closest to the other! And, do not put down the knee when falling!

What then is the correct way to take Koho Kaiten ukemi? Basically, you must take a big step back with the outside leg and bend that knee without folding the foot so that the bottom of the foot continues to touch the mat. Then put down the same side buttock and do Koho Kaiten by rolling back over the inside shoulder, and then, after rolling over, stand up in Hanmi, take Ma-Ai and face the other.

Depending on the particular technique received from the Nage, it can be appropriate to roll back over the outside shoulder (while still stepping back with the outside leg).

In any event, to perform such correct ukemi, you must utilize the elastic power of the legs sufficiently. In Aikido, the "elastic power" (or "bending and stretching power") is a basic method utilized to produce power or to soften power received from an opponent. In the case of backward ukemi, for example, only by using the elastic power of the back leg after the back roll, can you create the momentum for standing up.

You must use the Achilles' tendon and the hamstring muscle (as well as all other muscles and tendons below' the hip) as a part of creating power when you are being thrown, just as you use them when you are throwing.

Zenpo Kaiten Ukemi (Front Roll Ukemi)

Step forward with the outside leg, i.e. the leg which is further away from the Nage. If, for example, the right leg is the outside leg, extend the right arm forward while pointing its fingers inward and curve the right arm. Then make the outside of the curved arm touch the mat smoothly and roll your entire body forward through, in order, the right shoulder, the curved back, and the left hip.

To complete the roll and rise to standing position, fold the left knee and position the right knee in a bent but upright position. Upon arriving at this one knee kneeling position, by using the momentum of the rolling, put your weight on the ball of the right foot and do Tenkan at the same time standing up and positioning yourself at Migi Hanmi to prepare for the next move. Complete the movement by taking a sufficient Ma-Ai which prepares for the next move of the opponent. Therefore, when one practices this Zenpo Kaiten movement the goal should be to make it low and far (i.e. lower in height and further in distance).

Mae-ukemi (Break Fall) No.1

Step forward with the outside leg that is, the leg further away from the Nage (in this case the right leg). Spring with this leg as the pivot and do Zenpo Kaiten in the air. When landing on the mat, separate the body and arm so as to make a 45-degree angle between them and hit the floor first with the left arm in order to soften the impact on the rest of the body.

Then hit the mat simultaneously with the entire stretched left leg and the sole of the right foot and (the right instep and right knee are bent). At the instant the left leg and the right sole land on the mat, the upper body must be bent forward. (By this time, the elbow of the left arm, which hit the mat, must have already been bent and the left hand must have already supported the rising upper body.) Bending the upper body in this way is necessary to protect the internal organs from the impact.

It is important to keep the legs spread apart sufficiently because if the right knee cannot withstand the momentum generated by the impact and as a result collapses to the inside, the inside of the right knee must not hit the left leg.

Immediately after the left leg and the right foot land on the mat, using the momentum generated by the movement, twist the hip back to the right, and while standing up using the right knee as a pivot, do Tenkan with the left foot as the pivot and assume a Hidari Hanmi stance in order to be prepared for any move of the opponent.

Depending on which Nage waza (Throwing Technique) is employed, Zenpo Kaiten ukemi (Front Roll) may not be sufficient, and this is the ukemi which, in such a case, is necessary to protect one's self. It is like Zenpo Kaiten in some respects, but is different in others. You must learn the differences.

Train so that you can manage to do this ukemi flexibly when being thrown to the front, back, left or right.

Mae-ukemi (Break Fall) No.2

This ukemi should be used when being thrown directly down by techniques such as Koshi Nage or Kata Guruma, and it is almost the same as Mae-ukemi No. 1. In case of taking ukemi on the left side of the body, land on the mat with the left arm, left leg and the right foot sole simultaneously, while lifting the back (from the left abdomen to the left armpit) from the mat to protect the internal organs. Also, pull the chin forward to prevent the head from striking the mat. Both the angle of the arm and body as they hit the mat, and the distance between both legs are the same as the previous Mae-ukemi. Train very thoroughly because one receives a very strong impact when taking this ukemi.

Both of the Mae-ukemi waza are ukemi waza based on uniting oneself instantaneously with the body of the opponent who initiated the waza by making one point of body contact the pivot point. The pivot point is that point on the Uke's body where Nage's power is most loaded (or placed) onto the Uke, or, conversely, the point of Nage's body where Uke's weight is most loaded onto the Nage.

The pivot point can move (within a range) in the course of a technique, but at all times it is the point of strongest contact between the Uke and Nage. Therefore, one needs to clearly understand which part of the opponent's body (the part which the opponent's power is directly put on) one must utilize for this purpose. The point of contact is generally the shoulder, elbow, or hip.

When one is thrown in the air, one must put one's body in the correct position in order to land safely. However, while one is in the air and not in contact with any object, it is difficult to move in any way, much less move accurately. Therefore, one must use the reactionary power of the throw itself, received through one point of contact with the opponent's body (usually shoulder, elbow, or hip), to provide sufficient force to propel one to a position where one's orientation is regained.

This happens in one instant, so Uke must rapidly and accurately determine which part of Nage's body he will use.

Sokuto (Yoko-ukemi)

This ukemi should be used when being thrown down on one's side by Ashi Barai (Leg Sweep) or Okuri Iriminage.

In case of Hidari Hanmi (which would be the case if the left foot were the outside foot, i.e. the foot further away from the Nage), a moment before the left side of the body lands on the mat, one must hit the mat quickly with the stretched left arm, which is extended away from the body (maintaining an approximately 20 degree angle between the body and the arm), and shift the body's position so that the part of the body that lands first is the left part of the hip, and the part of the body that lands later is the upper left of the body. The instant the left hip lands on the mat, stretch both legs and kick them upward (twisting to the right front side of the body). This movement controls the balance of the body and prevents the left side of the body from receiving an abrupt and injurious impact.

Much training is required in order to hit the mat quickly and strongly with the extended arm, because in this case, one arm alone absorbs nearly all the impact received by the entire body.

The way of standing up is the same with Ma-ukemi.

There are also other ukemi such as Zenpo (Front Fall) or Koho (Back Fall) which are done when rolling is not possible due to insufficient space or other physical limitations. I would like to explain about these in the future.

It is necessary that one know when and how to do all types of ukemi. Just as Nage is required absolutely to make a posture based on the principle of reactionary power, Uke also must do ukemi based on the principle of reactionary power.

In other words, one must make sufficient use of the sources of reactionary power, which results from putting power on anything that has weight. For example, reactionary power would include the Nage's power, a part of the body, and the mat. Thus one can control one's own body. Unless one understands this principle, ukemi as practiced will never be the true ukemi.

You must practice until you are convinced that even when the power of an opponent is imposed on you with maximum force, if you can use the opponent's body in the correct way, you will be able to take the safest and most correct ukemi.

When one is being thrown, the power of the other is always imposed on a particular part of one's body. One must do ukemi either by utilizing the power which is imposed on oneself as the reactionary power, or by using the contact point between the other and oneself as a source for reactionary power.

Therefore, do not start your ukemi by "jumping" rashly in advance of the Nage's throw. Do not decide which to do, Ma or Kaiten-ukemi, before being thrown. Adapt oneself to the circumstances instantaneously and let the Nage's technique determine which you take. This approach must be thought through carefully and then consistently applied to practice.

Technical Aikido © Mitsunari Kanai 1994-96

|

|

Comics

Comics - Aikido Animals: The Heavyweight

By Jutta Bossert

The Heavyweight

Good partner, but is about twice your weight and has wrists like tree trunks.

Usually encountered during koshinage or yonkyo.

© Jutta Bossert - Used by permission.

|

|

Art. 8

A Distinctive Dilemma:

How Aikido struggles to find an identity in the modern world

(Part 1)

(Part 2)

By Michael Aloia

Dojo-cho Asahikan Dojo, Collegeville, PA

Even during its formation, Aikido has taken on many permutations and multiple interpretations. In brief, its origins are a mixture of physical movements, battlefield ideologies, cultural philosophies, and religious beliefs. More than 80 years after its coining, Aikido continues to take on many forms and interpretations. With the art now moving into a new era where anyone who may have been directly associated with O-Sensei in some capacity will be gone, many look ahead, with concern for the future of the art and its development.

Will there be a massive push to hold on to the remnants of the past and the traditional aspects of Aikido, or will things radically begin to change as a new generation of instructors rise? Will future generations of Aikido practitioners find themselves in an entirely new art form than their predecessors did? Will Aikido still exist?

Many critics believe that Aikido is overdue for a radical change, feeling as though it is a change that should have occurred decades ago. With the growing decline of interest in traditional martial art forms in general, some even feel that such a trend may lead the art, as we know it now, to disappear altogether; that such an evolution is inevitable for its survival. But how does an art move forward when the very definition of what it is, what its purpose is, and how it actually functions as a valuable art form continues to remain in question to outsiders and practitioners alike?

Over the last 20 years, it has been no secret that Aikido has struggled to find its place in the modern martial arts world, especially in America, as MMA has taken such a spotlight along with the rise of the internet. The argument has always been that Aikido is not worth a damn in a street fight and that its practice is a waste of time. In a fists-to-cuffs, knockdown, drag out fight, this may not be entirely untrue, from a certain point of view.

However, the real culprit may lie more in Aikido's own definition and presentation of itself and its practitioners' true understanding of the art, training habits and its purpose, rather than its lack of street credibility in comparison to other styles. Another question to ask regarding Aikido's validity is, was street credibility ever really the art's true goal or a consideration when Aikido was first being conceived? Is such an idea that of subsequent generations attempting to put more to it such as a physical purpose, to compete with other forms and styles?

The old adage when representing or defending aposition is to avoid stating or discussing what something does not have or does; to avoid inadvertently supporting the opposition. However, given the topic of discussion, briefly covering some examples of the above seems prudent to gain a clearer picture of what the art does not offer its seekers.

Aikido is not a fighting or sparring art form. Traditionally, Aikido does not offer a competitive component for its practices. Though there are some forms of Aikido that do include competitions, these forms tend to be hybrids of the original intent of the art and are often frowned upon or ignored by more traditional practitioners. Many will argue that without some form of competition, there is no real way to "pressure test" the techniques and their applications, thus limiting or removing any credibility. Conversely, given Aikido's original design, competition, in the art's current traditional state, does not easily lend itself to the arena without a number of modifications.

Aikido is not necessarily a self-defense form of tactics and techniques. Though there are aspects that can be applied in such a scenario if understood, in general, Aikido is more in line with a self-preservation approach that teaches its practitioners how to get out of the way of a moving train rather than staying on the tracks and meeting it head on.

Aikido does not offer tactics for dealing with a toe-to-toe, physical confrontation. When compared to Western Boxing, Aikido is on the other end of the spectrum. Boxing deals with the engagement of conflict where Aikido tends to focus on the disengagement from or de-escalation of conflict.

Though Aikido is considered a grappling art form, debatably, it does not necessarily equip practitioners for dealing with the clinch. Nor does it traditionally incorporate sweeps and basic takedowns. Styles like Judo and Jujustu tend to provide more reasonable and effective alternatives to such encounters, giving practitioners a stronger level of comfort working in uncomfortably close quarters.

Aikido works with three strike variations primarily; shomenuchi, yokomenuchi, and tsuki, though with its arguably limited range of weapons, the art doesn't dwell heavily in teaching practitioners how to deliver a mechanically sound and effective blow. Karate and other related stand-up styles tend to focus on the necessity of proper striking and anchor their core teachings on generating power and stance, offering practitioners a strong base to work from for exchanging blows.

Based on the above, it would appear that Aikido may be giving critic sentiments a winning position and possibly even proving them entirely correct. This may also be where much of the misunderstanding tends to take place, where Aikido, possibly by its own wrongdoing and undoing, may misrepresent itself unknowingly. There is more to this story than we realize. There is more to Aikido.

(Continued in Part 2.)

To better clarify aspects of Aikido and its training purpose, the following briefly outlines several basic foundational points the art tends to focus on.

Aikido is defined as a way of harmony per the founder of the art, Morihei Ueshiba. However, with reflection, we can come to realize that Aikido was Ueshiba's personal way of harmony that ultimately made up the core of what Aikido has become: his life, his experiences, and his spiritual journey materializing into a physical form from his own view - this one man's interpretation. Over time, that definition or interpretation became the art for those who followed or attempted to follow. Aikido was Ueshiba's world.

Aikido speaks of finding harmony. In truth, harmony can ultimately be found in any endeavor and is not exclusive to Aikido. With Aikido, practitioners are following a path defined by a single man's life interpretation of a martial art including physical and philosophical aspects too. Practitioners are striving to recreate that interpretation for their own benefit, which in itself can be perceived as a futile endeavor as Ueshiba's experience was solely his own. However, with dedicated and diligent practice, aikidoka can begin to create their own way or "do."

The "do" is exclusive to the practitioner. It is how aikidoka integrate, execute, and experience the "aiki" that exists all around them. Each will have a different interpretation, a different experience. Even though some experiences may be similar to another's, they will never be exactly the same. Within the arts, there are often those who spend their time searching for what others have felt or done rather than allowing themselves to feel things for themselves and create their own experiences. The latter is finding harmony within; to do otherwise is disharmony, which, for another study entirely, is the essence of living Budo.

It should be briefly mentioned that the act of inflicting any level of harm, pain, discomfort, or worse on another is in no way a form of harmony, based on its given and/or perceived definition within Aikido and defined by the standards of any sane individual. Such acts are more aligned with disharmony than with harmony itself. Part of the misunderstanding can lie here as there is a bit of discord that occurs in the pursuit of achieving harmony while executing disharmony to another. To say that Aikido does not inflict pain or injury is a misconception as the art form clearly demonstrates such techniques, especially since a majority of Aikido has its roots in aikijutsu/jujutsu. Pain compliance appears, to some degree, in almost all martial art forms.

The harmony sought within the physical confrontation in Aikido is the connection and/or alignment of energies between uke and nage or attacker/defender. Practitioners look to avoid any resistance, working with what is given in that moment, developing the proper mechanics to achieve harmony while moving in and out of disharmony. The harmony sought is the ability to execute techniques without muscle or force.

What Aikido does offer in the way of achieving internal harmony in potentially threatening situations is the awareness to the level of discomfort we choose to either endure or execute. In addition, Aikido offers the discernment to assess the severity of the circumstances we experience and to determine our level of involvementin and/or commitment to those experiences. Harmony is a "connectivity" to what is around us and how we choose to interact with those connections. Aikido teaches us the use of degrees of control and degrees of execution. Practitioners have the capacity to respond accordingly, not impulsively.

On the physical end, Aikido is said to be derived from the use of the sword; primarily an empty-handed application of sword movements but also includes both wielding the sword and defending against it. This approach does offer practitioners a way to develop precision and accuracy while understanding the importance of getting off line and avoiding the attack. The coupling of basic sword practice further reinforces these concepts of distance and projection, primarily working with a partner in the middle ranges. Additional distance ranges, long and short, are studied with the inclusion of the jo and the tanto; both offering similar benefits based on their training.

Aikido teaches the understanding of proper "maai," or distance, and how that distance affects the things we do. Too far away causes over reaching, an unstable position and ineffective technique. Too close, and there is no functional efficiency. Understanding distance gives space. Space gives time, and time gives space. This aspect is the foundation of understanding and implementing the use of proper distance. With empty hands, Aikido generally works in the mid to close range during its practice.

Aikido's physical practice centers on movement and the relation of that movement while in motion with another; two bodies in motion looking to find harmony. The practice is an understanding of what levels of impact that moment has to offer, thus becoming an exploration of self as well as a reflection of a choice in dealing with confrontation. Through its physical training, a moment-by-moment experience is ingested that better equips practitioners on the mental and spiritual levels. The physical aspects are kept simplistic and, at times, stylistic so that such mental and spiritual levels can be achieved in the practitioner's own time. It is not about winning or losing but overcoming- overcoming the obstacles life often places throughout daily life.

Aikido also offers education in moving things that don't want to be moved. Rather than man-handling training partners, subtle changes in stance, center, balance, direction, height, angle, and pressure can make all the difference. The art works to keep a level of individual calm and relaxation that starts with maintaining regular breathing patterns to achieve such a state.

As well, Aikido offers practitioners a way to learn how to fall. Though "ukemi" is commonly translated to falling, more accurately, it relates to one's ability to receive the energy that one comes into contact with - falling is just one part of the ukemi approach. It's about moving and the ability to move in a way that connects and maintains harmony.

More than just a generalized martial art form or even a style, Aikido can actually be defined as a sophisticated developmental tool to gain and build personal skills. These skills are attained through a highly concentrated focus and understanding of: motion and movement, distance and timing, spatial awareness and position, mechanical effectiveness and efficiency, and proper breathing and balance. These elements help practitioners become hyper-in tune with one's own abilities while promoting a calm and stable state of mind, body, and spirit; thus, giving form to the function and function to the form.

With any physical practice, a practitioner's level is determined by the level of commitment given. This reciprocal practice is the basis for the uke/nage relationship and how training partners work to interact with one another while on the mat. This yin/yang model aids in the learning and development of each practitioner, removing resistance so complete immersion can be achieved. The goal is never to hurt or injure another but to raise them up; in their abilities and skills, both on and off the mat. Such practice enhances the learning/teaching experience.

On its philosophical and spiritual intent, Aikido looks to elevate the experience by strengthening the connection. "May the highest in me bring out the highest in you." By intentions and experiences aikidoka can better serve others and enhance training simply by doing - and wanting to do - the best they can at any given moment. By appropriate, harmonious actions and deeds, others will respond in kind - a ripple effect that has positive results. This appears to be Aikido's true way of harmony. It's about what it does to the individual and how that individual makes an impact on others, paying it forward and making a difference with each encounter. Each person has that power.

Aikido offers many people many things - some similar and some different - and that's what makes the art so unique and versatile. However, this may also be why coming to one true universal definition of the art - what is its point and purpose and adapting one method of how it should be practiced - is also so diverse. The art is open to interpretation based on any one individual's or group's experiences. More than an art or even a style, it can be a mindset, an intent. Aikido itself serves as a personal endeavor, a path one ultimately walks alone but with others simultaneously, sharing time and space but in the end, making one's own way of it.

So where does all this leave Aikido and its coming future? Without a crystal ball as many have said, unfortunately, no one really knows for sure. The hope is that the art will continue on for many generations to come. And as it does, it will continue to grow and foster itself as a way for individuals and groups to find one's self and become a better version of said self. Regardless of position, style or even training methods, it can be said that Aikido's true strength lies less in its technique or teaching methods and more in its diversity and ability to modify itself to the situation; giving the seeker exactly what they are looking for.

Maybe the real goal of all this is not to unify to a particular belief and/or standard but to move forward, letting go of all the perceived differences and accept that no two will ever be the same regardless of any effort to make them so. Acceptance allows practitioners to focus their energies on something greater; on bettering themselves and the immediate world around them; finding their own path and living their journey.

|

|

Art. 9

Seminar in San Salvador

By Armando de la Rosa

Dojo-cho, Kokyu Dojo - Aikido El Salvador, El Salvador

I would like to express my sincere thanks to Robert Zimmermann Shihan, president of Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance and dojo-cho of Toronto Aikikai, as well as his students Yelitza Cuevas Shidoin and Eric Lavigne Shidoin, for teaching an unforgettable seminar in San Salvador on July 12 and 13, 2025.

It was a privilege to have the guidance of Zimmermann Sensei, whose high technical quality, powerful and precise Aikido, and generous teaching spirit left a profound impression on all the participants. His willingness to share his knowledge with humility and without expecting anything in return is an example that deeply inspires us.

It was a great joy for us to welcome back Zimmermann Sensei, who has visited El Salvador on several previous occasions to generously share his knowledge. His most recent visit was approximately eight or nine years ago, so his return was especially meaningful and emotional for our community.

Likewise, I would like to extend our gratitude on behalf of our dojo to Yelitza Cuevas Shidoin and Eric Lavigne Shidoin, whose classes brought clarity, dedication, and technical richness to the seminar, complementing in an excellent manner the work done by Zimmermann Sensei.

The seminar was enthusiastically attended by both adults and children, who shared the tatami in an atmosphere of respect, joy, and learning. We would especially like to highlight the invaluable support of the Aikido students from El Salvador and the children's parents, whose collaboration was fundamental to the organization of the event. Their commitment and willingness made it possible for this seminar to take place under the best conditions.

I would also like to thank Sensei Pablo Buenafe and his wife Rosina, who came from Guatemala to participate in the seminar.

For our small dojo, Kokyu Dojo, in El Salvador, this experience has been an important opportunity for growth, not only technically but also personally. We are deeply grateful for the closeness, respect, and community spirit that the three visiting instructors shared with us. Thank you very much for your dedication, your time, and your friendship. We look forward to meeting you again on the tatami.

|

|

Art. 10

Dojos granted Provisional Member status

We are pleased to announce that the following dojos have been granted Provisional Member status:

- Aikido Fujisan Dojo, located in the city of Caracas, Venezuela, led by dojo-cho Maykell Torres, sandan.

- Aikido Sakura Dojo, located in the city of Barquisimeto, in the state of Lara, Venezuela, led by dojo-cho Angel González, sandan.

Congratulations!

|

|

Art. 11

A new beginning

By Maykell Torres

Dojo-cho, Aikido Fujisan Dojo, Venezuela

About the Dojo

The dojo takes its name from Mount Fuji, a symbol and natural icon of Japan, whose characters represent: FU = Wealth. JI = Samurai, warrior. SAN = Mountain.

The Dojo began operations in April 2014 in Panama City, when Maykell Torres and Geisa Cárdenas joined forces to cultivate the practice of Aikido in the city.

The fundamental objective of our organization is to comply with the guidelines of the "Hombu" headquarters in Japan regarding the teaching of the "Art of Peace" and to spread and popularize Aikido as was the will of its creator O-Sensei Ueshiba Morihei, who stated that if all men on earth practiced Aikido, wars would not exist.

In August 2023, the dojo closed its doors in Panama and after a period of 2 years, after overcoming several obstacles and with great joy, Aikido Fujisan reopened on May 7, 2025 in Caracas, Venezuela.

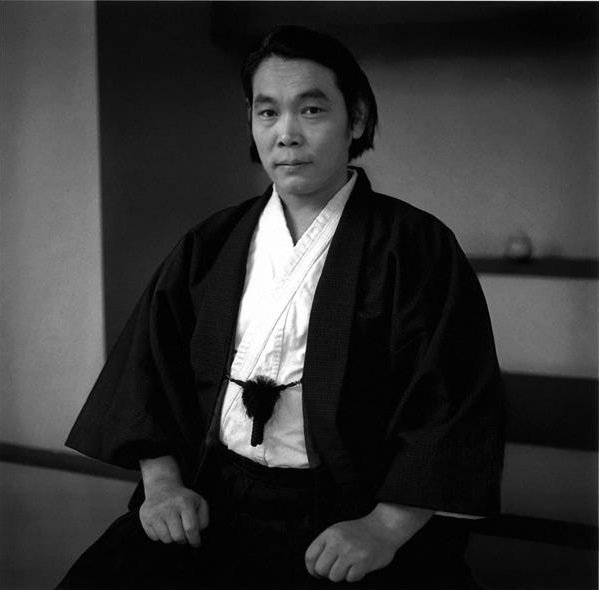

About the Instructor

Maykell Torres began his practice of Aikido in 2003 under the instruction of Jesús "Chucho" Gonzalez Sensei. In 2008 he moved to Margarita Island and received instruction from Manuel Cormenzana Sensei and Luis Marín in Muso Jikiden Eishin Ryu Iaijutsu. In 2014, he moved to Panama, where he started the Fujisan Aikido Dojo that same year, organizing international seminars and training new students in Aikido and Iaijutsu. In 2015, he presented his Shodan with Zimmermann Sensei, and in 2024, his sandan, also with Zimmermann Sensei.

He has attended seminars and received instruction from teachers such as Yoshimitsu Yamada Sensei (RIP), Donovan Waite Sensei (RIP), Robert Zimmermann Sensei, Peter Bernath Sensei, Angel Alvarez Sensei, Yesid Sierra Sensei, among others. He currently continues his study of Aikido as a student of Jorge Russo Sensei.

|

|

Art. 10

Art. 11

Art. 12

Art. 13

Art. 14

Art. 15

Dear Dojo-cho and Supporters:

Please distribute this newsletter to your dojo members, friends and anyone interested in

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance.

If you would like to receive this newsletter directly, click

here.

|

|

|

|

SUGGESTION BOX

Do you have a great idea or suggestion?

We want to hear all about it!

Click

here

to send it to us.

|

Donations

In these difficult times and as a nonprofit organization, Shin Kaze welcomes donations to support

its programs and further its mission.

Please donate here:

https://shinkazeaikidoalliance.com/support/

We would also like to mention that we accept gifts of stock as well as bequests to help us build

our Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance endowment.

Thank you for your support!

|

|

|

|

|

|