Comments

Header

News from Shin Kaze

January 2024

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance is an organization dedicated to the practice and development of

Aikido. It aims to provide technical and administrative guidance to Aikido practitioners and

to maintain standards of practice and instruction within an egalitarian and tolerant structure.

|

|

Table of Contents

Introduction

Introduction

Happy New Year Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance members!

We hope that you, your loved ones, and your dojo members have had a wonderful holiday season and

have resumed vigorous practice.

This is the first issue of our newsletter for 2024, which once again contains a variety of very interesting articles

that reflect our diverse membership.

We hope you will enjoy this newsletter, and as always, we welcome and encourage everyone’s input and thank the authors

and artists who contributed their thoughts, tips, drawings and pictures.

In addition to your articles and views, we invite your feedback in the form of letters to the Editor.

We want to thank each and every one of you for being members of Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance and

to congratulate all those who were promoted during the past year and especially at the 2024 Kagami

Biraki ceremony. We are very proud of everyone's progress and the example being set for others.

Barbara, David, David, Robert

Directors - Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance

|

|

Art. 2

Hombu Dojo Announces 2024 Shin Kaze Kagami Biraki Promotions

The Aikikai Hombu Dojo 2024 Kagami Biraki Ceremony took place on Sunday January 14, 2024.

The following links show videos of the demonstrations (embukai) during the ceremony by

Doshu Moriteru Ueshiba and Dojocho Mitsuteru Ueshiba,

Doshu Moriteru Ueshiba and

Dojocho Mitsuteru Ueshiba.

A total of 1132 aikidoists were promoted worldwide.

Here is the complete list.

New Year promotions for the following Shin Kaze members were announced at the celebration:

Rokudan (6th dan)

Fiona Blyth - The Wind On The Top Of The Mountain - United Kingdom

Carlos Adolfo Calatayu - Shinka Dojo - Argentina

In addition, the following Shin Kaze members were promoted throughout 2023 and their ranks registered at Aikikai Hombu Dojo:

Yondan (4th dan)

Christopher Niskala - Framingham Aikikai - USA

Sandan (3rd dan)

David Beebe - Framingham Aikikai - USA

Basia Halliop - Toronto Aikikai - Canada

Esteban Lagiglia Karami - Chikara Dojo - Argentina

Silvina Mora De Calatayu - Shinka Dojo - Argentina

Ezzard Charles Along Neri - Toronto Aikikai - Canada

Guillermo Ruiz - Zen Bu Dojo Aikikai - Venezuela

Abdellatif Samiky - Toronto Aikikai - Canada

Nidan (2nd dan)

Lester Emilio Machado Martín - Kan Sho Ryu Dojo - Cuba

Antonio Pardo IV - Brampton Aikikai - Canada

Mariano Pedraza - Samurai Dojo - Uruguay

Michael Raiter - Framingham Aikikai - USA

Leonel Sánchez Sotolongo - Kan Sho Ryu Dojo - Cuba

Pablo Vitelio - Samurai Dojo - Uruguay

Shodan (1st dan)

Jason Bestor - New Haven Aikikai - USA

Eduardo Julián Bitancurt - Meiyo Dojo - Argentina

Carlos Bucheli - Zen Bu Dojo Aikikai - Venezuela

Horacio Jesús Gazzola - Meiyo Dojo - Argentina

Sean Griffin - New Haven Aikikai - USA

Peter Krala - New Haven Aikikai - USA

Guillermo Maldonado - Shinka Dojo - Argentina

Alejandro Monzón Díaz - Kan Sho Ryu Dojo - Cuba

John Oh - New Haven Aikikai - USA

Yaleh Zan Paxton-Harding - Toronto Aikikai - Canada

Ryan Pope - Brampton Aikikai - Canada

Yasmani Rivero Olmo - Kan Sho Ryu Dojo - Cuba

Elise Springer - New Haven Aikikai - USA

Ernesto Tápanes García - Kan Sho Ryu Dojo - Cuba

Mikveh Warshaw - New Haven Aikikai - USA

Our heartfelt congratulations everyone, please keep up the good work!

|

|

Art. 3

Reaching Rokudan: reflections on my path

By Adolfo Calatayu Shidoin

Dojo-cho Shinka Dojo, Argentina

Sensei Zimmermann has immensely honored me with the rank of Rokudan, and this leads me to outline a series of reflections on some issues on my Aikido path.

The other day I was telling Sensei that when I started my practice, my greatest idol was a 2nd kyu. I watched him on the mat and thought that I would never reach that level of sophistication. Time went on, as is its nature, and my role model abandoned practice without reaching 1st kyu. I continued practicing; Aikido was a fever that occupied and consumed my entire life, like a fire that never extinguishes. I imagine many readers share that feeling.

Kurata Sensei, faced with taking Shodan exams, asked us to write something about Aikido for our graduation. Of course for many, this implied a high degree of stress, but not for me, since at that time I was quite oblivious to many thing. What to write about considering the vastness of the topic? Technical, philosophical aspects, personal experiences on the mat? It is an inexhaustible topic. When I asked the Master what in particular I should write about, he answered amusingly "about whatever you want." Leaving aside the nonsense I wrote in that easily forgettable essay, the only portion that resists the passage of time (to my modest understanding), is something that I reread from my writing a month ago, that to me Aikido means Beauty, Joy and Mystery.

Like so many, like everyone, I have gone through very difficult moments in life, hard moments, moments in which I asked myself how to continue. Fortunately I had Aikido and the Aikido family. I feel that Aikido is always "there", to help us, to strengthen us, elevate us, help us grow, tolerate the intolerable. It is truly very difficult to talk about Aikido, and not because it is an abstract concept, which it is not, on the contrary it is very real and concrete, but because its meaning and the effects of the development that occur during its learning are so complex that they make it a very arduous task.

I always had a very personal experience regarding when I was informed that I had to take an exam for a new graduation, both kyu and dan - the exception was when I took the shodan exam, since as I said, I was very oblivious -, and I never felt I had the ability or the merit to advance to the new rank, a feeling that went beyond the moment of graduation. But after a considerable time, something strange, something even magical happened where I did, indeed, feel like the owner of that belt or rank. It is something very subjective, like almost everything.

I think if I remember correctly, Yamaguchi Sensei stated that Aikido was an activity that belonged to the right hemisphere, to explain the complexity of its learning and the refinement of its movements. Every time I get on the tatami something new happens, it is a permanent challenge and a perpetual discovery.

I am very grateful to my teachers for the generosity, patience, knowledge, time and nobility they gave me. Without them I could never be at this point on the path, and any mistakes or clumsiness that I may have in practice are completely my own mistakes. Thank you, thank you very much for the wonderful gift of Aikido that continues to manifest Grace, Beauty, Joy and Mystery at all times.

Adolfo Calatayu Shidoin

Rokudan |

|

Art. 3a

In Memory of Yoshimitsu Yamadada Shihan

February 17, 1938 – January 15, 2023

January 15, 2024, marks the first anniversary of the passing of Yoshimitsu Yamada Shihan. Born in 1938, he started his Aikido career at Hombu Dojo in 1956.

He moved to New York in 1964 as chief instructor of the New York Aikikai and was the first Shihan to reside permanently in the United States. He was Technical Director and President of the United States Aikido Federation and Sansuikai International, and a member of the IAF Board of Governors.

A key figure in the spread of Aikido worldwide, he regularly traveled giving seminars throughout the United States, Canada, Latin America and Europe.

|

|

Art. 4

Te No Uchi

By Richard Galvis

Escuela Nacional de Aikido – Zen Bu Dojo – Aikikai, Caracas, Venezuela

Before making a literal (and simplistic) translation of 手の内, we are going to try to introduce ourselves to the concept

of the terms that make it up to understand the meaning of the phrase beyond the obvious.

Although 手の内 is made up of 3 characters, in reality we can affirm that it is made up of 3 ideograms or concepts,

namely: 手 (Te), の (No) and 内 (uchi).

手 (Te) literally translates as “hand” but also in its plural form “hands”, as when writing in Japanese there is no

difference between the singular and the plural, the plurality or singularity of the subject is implied by the context

of the sentence.

の(No) is a linguistic particle with different applications. It can be used to replace the noun when you want it to be tacit, for example in Shiroi Yama Wa Takaku (the white mountains are high) we can use Shiroi no Wa Takaku (white ones are tall) in a context in which it is understood that we are talking about mountains, then の(No) replaces the noun “mountains”.

の(No) can be used to change nouns and give them a characteristic, that is, apply an adjective to them, for example 花Hana (flower, noun) becomes 緑の花 Midori No Hana (green flower, where green is the flower adjective).

の(No) in a third case is used as a possessive particle that symbolizes a relationship of subordination between two ideas,

for example, in 私の木刀 (Watashi no bokken), Watashi is translated as I and bokken refers to our well-known bokken sword.

In this sentence の reflects a possessive article that can be translated by “of”, so that literally the phrase

"Watashi no bokken" would be translated as "I of bokken". Noting that in Japanese the order of the sentence is reversed,

it is more correct to make the translation as “Bokken of I”. Of course that is a primitive translation, and the correct

one is "My bokken", but this helps us to understand the relationship of subordination of one idea (bokken) to another (I).

It is not just any Bokken, it is "My bokken". For this case then, we will affirm, being simplistic, that の can be translated

as “of”, becoming a possessive article.

内(Uchi) is a quite deep and complicated concept to analyze, because 内 (Uchi) is above all an idea of Japanese culture,

it is a concept of being inside something, but not only being physically inside but of belonging. For example, if you go to Japan

as a tourist you “are inside” Japan, but being inside does not give you a sense of belonging, you are inside but you do not belong,

let's say that in that case there is no Uchi.

内(Uchi) we can then affirm translates as “within” or "inside" but with a connotation of intimate belonging.

It is not simply being inside but belonging to that “within”, as when you affirm “she is inside my soul”

referring to the fact that “she” and your own soul are the same thing, “she” is there as something that belongs,

not that she simply happens to be there.

Then having made this brief breakdown of the terms that make up 手の内 we can try to translate it:

Te No Uchi, literally means “hands inside” or rather “the hands inside”,

and remembering that in Japanese the sentence is written in an inverted way,

it would be “inside the hands” or also “inside the hand”, where the plurality of the subject depends on the context.

Thus 手の内 can be understood as the action of taking something (grasping) but not simply placing it in the hands

but to make it belong to that “within”. It is not about physically holding but holding with the intention of achieving

an intimate connection between the holding hands and the held object.

So when you hold the Tsuka (the handle of a bokken, iaito, etc.), beyond the correct holding technique (with all the variants

of style or school that may exist), there must be an intention of commitment between the hand (or hands) that hold and the

object held (in this case the Tsuka). That intention is 手の内, it is through that intention that the Tsuka will not only be

inside the hand but will be part of it, the hand and the Tsuka must merge, be part of the other,

and it is then, in that node where the arm and the weapon merge physically and energetically and become one,

that 手の内 allows the weapon to be an extension of the arm and vice versa, and being one, the energy and intention of the

movement flow in harmony from one to the other. Without intention there is no 手の内 and the weapon is just an inanimate

object held in the hand by a simple physical grip, there is no harmony, nothing flows towards it, and the blow given with

this grip will be imperfect and incorrect even if it follows to the letter each step of the grip technique.

Without 手の内 the blow or cut is empty.

The same thing happens (or should happen) during empty-handed action in Aikido and other martial arts.

When uke holds tori there must be intention for 手の内 to exist. Without it there is nothing, neither union nor harmony,

uke and tori remain two separate entities and therefore there is no flow of vital energy (Ki).

Without 手の内, we can affirm there is no Ai-Ki-Do, only empty grips and movements that are not harmonious.

For some authors (of course with knowledge far superior to that of this beginner)

手の内 is an action that is applied right at the moment of impact. For example, quoting the following text:

“… one has to apply tenouchi right at a certain moment of the blow. If tenouchi when striking is too weak,

the opponent will be able, if he wants, to hit our shinai and even disarm us, so at that exact moment of the blow

you must hold on tightly, but only at that moment. (https://kendoblog.es/2009/09/30/tenouchi-手の内)

In my opinion the author makes a mistake by confusing the strength of the grip with the intention.

You can grab your weapon with as much force as possible, but that's not 手の内, it's just force.

On the contrary, if you can hold the weapon relatively delicately, but feeling that the weapon and the arm (or arms)

are a single unit, then that is 手の内.

Applying force to the grip right at the moment of contact is of course part of the technique.

Before contact, the grip must be relaxed (but firm) to prevent the rigidity of the grip from hindering movement during

the execution of the technique. Just after ending the contact, the hands must return to a state of relaxation and firmness

to allow entering zanshin, but 手の内 must always be present, before, during and after the execution of the technique.

From the moment the hand embraces the Tsuka (or the opponent's forearm if we are practicing empty-handed) until it is released

again (after Noto, for example) there must be that intention or feeling that the weapon is an extension of the arm itself,

regardless of the force applied.

Thus, 手の内 is above all a concept that encompasses the physical and the ethereal, which in turn is a

philosophical/spiritual aspect, and also a physical one, since without physical grip of course there can

be no 手の内, just as without the intention of letting one's chi flow through the grip there can be no 手の内.

Everything else concerning the physical grip, such as the position of the hands, the separation between them,

the pressure exerted during contact, etc., is technique, which is still important for execution ( and that must be studied

and mastered) but that is empty and incomplete if the concept of 手の内 is not mastered. Then we can affirm that the

grip is the body and the intention or sensation of 手の内 is the spirit, and just as our body and our spirit are different

but complementary so that we can exist, in the same way they are complementary so that the technique can exist in a suitable way.

|

|

Art. 5

Building Trust on the Mat

By Michael Aloia

Dojo-cho Asahikan Dojo, Collegeville, PA

Trust is the glue that holds most things together. Trust is the distinction between what is perceived to be real and what's not. The idea of "being real" often invokes a mental and emotional picture or feeling that defines our state of belief; making things authentic and logical, and therefore trustworthy. In any relationship, trust plays a major role in ensuring that what we are doing, what we are involved in, is worth the effort. It's a level of stabilization that fuels the long haul and provides point and purpose for our continued involvement and further developments.

Trust in martial arts training is no different; we are building relationships with our partners and ourselves. Trust often emphasizes both our strengths and our shortcomings when it comes to what we understand, how we perform, and our level of engagement. Trust, or the lack thereof, can frequently impact our overall abilities and potential development. Without trust, growth becomes stagnant or even non-existent in some cases. Limitations are reached long before any lasting quality can be achieved or built upon.

Lack of trust in what one does as well as one's partner most commonly starts with a lack of trust in one's self; struggling with one's own abilities and understanding can be the root cause in some cases. We can't see past our own shortcomings, so we often unknowingly pass those shortcomings or assumptions onto others. Boiling it down, lack of trust comes down to fear; a level of fear that prevents us from making any real commitment. Trust requires commitment. That level of fear puts us in the mindset of not letting go, not being in the moment, and micromanaging things every step of the way. The kind of progress we want, that we need, is missing.

Trust aids in the learning/teaching process. While the main instructor lays out the lesson plan for the class, it is in the trenches, during partner drills and exercises, that the true development takes place. Partners learn from one another, assist one another, and grow with one another. But the opposite is as true as well. Partners can easily pick up bad habits from one another, struggle with one another, and diminish results with one another. It's a symbiotic circle of progress whether we realize it or not.

We most notably see this sort of thing in the uke who is struggling with ukemi, especially after being on the mat for a significant length of time. There is hesitation and reservation. There is no real commitment, thus there is no improvement or growth.

How then do we build trust and begin moving forward? How do we overcome being our own progress obstacle? Trust is developed through attention to detail; by taking the time and the effort to know what it is we are doing; how to do it, why to do it, when to do it and to what level is required to do it. The more we know, the more we grow. Knowledge is the great leveler when it comes to building trust. The more comfortable we become and are in our own understanding and abilities, the more we will trust in the process to work in the moment and avoiding self-sabotage situations that not only affect us but our partners as well. Trust begets trust; trust in ourselves leads to having trust in others. Training becomes a win-win scenario; everyone benefits.

Most of the time, lack of progress on the mat can be attributed to a lack of trust to some degree solely on our part, barring there isn't any physical, medical, or learning disability conditions and aside from any safety concerns. Trusting one's self is having the patience, the knowledge, and the understanding of that knowledge to build upon, integrating it into what we do and how we go about doing it. Like regular training, trust is an ongoing cycle of moving forward and striving to make a difference in where we are presently to where we want to be tomorrow and that is where lasting growth takes place.

|

|

Art. 6

Sei chu sen

By C. Omar. D. Bravo

Escuela Nacional de Aikido – Zen Bu Dojo – Aikikai, Caracas, Venezuela

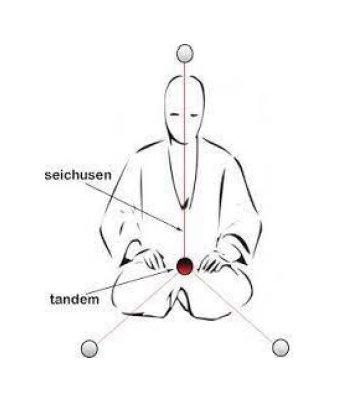

Sei chu sen is a fundamental concept, common to all Japanese martial paths or Budo. The kanji 正 中 線 literally translates to "correct center line", the ideogram corresponding to center also conveys the meaning: internal.

We could understand it as the imaginary line that runs up and down your entire body, from the crown of your head, through the tandem (or Dan Tien), to your feet. This line divides the body exactly into two equal halves, which is why its use, through consciousness, facilitates a stable, fast and subtle quality of movement. It also represents a radial axis on which to rotate in a balanced manner.

Likewise, it is considered that the movements calibrated from the sei chu sen have a maximum of efficiency in terms of energy utilization with respect to the power generated, it must be taken into account that "Aite " or "uke" also has a sei chu sen and that the point of convergence of these two centers is called sei chu men.

In general, the correct use of the sensation of sei chu sen during practice can generate greater effectiveness in: movements, maintaining a more stable posture (kamae), increase the power and precision of atemi, create explosive compression and expansion, turn in a balanced manner, control the ma-ai (effective distance) with respect to the opponent, create opportunities of kuzushi (imbalance).

According to Dr Hideo Takaoka, the sensation of the central line is a foundation for developing body awareness which is the gateway to a deeper relationship between body and mind, concepts that are repeated in philosophical ways such as the fourth way of G.I. Gurdjieff in which the sensation of the body is a kind of anchor for self-remembering, which is why the use of the central line is the purpose behind enigmatic practices such as the dance of the dervishes.

By going down deeper philosophical paths we can reach amazing discoveries. For example, if the universe were infinite, it would be infinite in all possible directions. If this is so, no matter how much space we move in a given direction, we would never be closer to the "edges" or the end. of the universe. From this it follows that, for each of us, objectively, the sei chu sen constitutes not only the center of our body, but also the center of the universe itself, as well as also the sei chu sen of each of the other apparent "individuals" is also objectively the center of the universe itself. This seems to demonstrate the fundamental unity of all things: the center is everywhere.

|

|

Comics

Comics - Aikido Animals: The Newbie

By Jutta Bossert

|

Have you ever noticed that there are sometimes stereotypes of people you meet at every Aikido seminar?

Now imagine what kinds of animals they would be …

|

The Newbie – Has never been to a seminar before.

Is confused.

© Jutta Bossert - Used by permission.

|

|

|

Art. 8

Book Corner: Technical Aikido

By Mitsunari Kanai Shihan, 8th Dan

Chief Instructor of New England Aikikai (1966-2004)

Editor's note: In this "Book Corner" we provide installments of books relevant to our practice.

As continuation from the previous issue, here is Part 2 of Chapter 3 of Mitsunari Kanai Shihan's book "Technical Aikido".

CHAPTER 3 - PRINCIPLE OF BODY MOVEMENT (UNTAI NO GENRI) - (Part 1)

Much of the language typically used in descriptions of AIKIDO technique reflects an over emphasis on footwork. Some common expressions reflecting this overly restrictive viewpoint include feet/leg movement (HAKOBIASHI), footwork (ASHISABAKI), and treading (ASHIBUMI).

The critical aspect of a technique is not in the movement of the feet and legs. This is because when a body movement exceeds a certain speed, it is impossible for the feet and legs to follow and keep pace. (Movement in the darkness where it is necessary to feel ones way along is an exception to the rule.)

Body movements naturally originate in the KOSHI which is the largest mass in the body. (The KOSHI should be understood to include the entire hip area of the body, including the buttocks.) The center of the KOSHI is the TANDEN, and TANDEN is also the center of the entire body.

In order for the human body to constantly maintain good balance, the KOSHI and the head (which is the body’s second largest mass) must be correctly aligned. When the weights of the head and KOSHI become misaligned, the posture can be re-balanced or corrected (very subtly in many cases) by moving and realigning the KOSHI and legs in a new position.

Executing complicated body movements is made possible by this cycle of moving the weight of the KOSHI and the head, destabilizing the posture, and realigning these weights by moving the legs and hips to a new, stable posture.

It is important to begin to understand the relationship of the head and KOSHI. However, because their relationship can become very complicated, a detailed explanation will be postponed until later. For the remainder of this discussion, we will define KOSHI as including both the head and the trunk, that is, as the whole weight of the upper body that rests on the KOSHI.

The entire upper body weight rests first on the KOSHI but then splits into two halves that extend through the legs and eventually rest on the two feet. Thus, when the KOSHI moves, the body weight will automatically shift. This results first in movement of the legs and feet, and then in movement of the whole body. If the weight shift is slow, the reaction of the two legs will be slow as well. Conversely, if the weight shift is fast, then the response will also be fast.

Whether one realizes it or not, the ability to move freely in any direction is made possible, and is triggered, by movement of the KOSHI which generates momentum and in turn is followed by movement of the legs. If one wishes to make refined movements, it is important to be conscious of the function of the KOSHI and fully utilize it.

End of Part 1.

CHAPTER 3 - PRINCIPLE OF BODY MOVEMENT (UNTAI NO GENRI) - (Part 2)

Basic forward and backward movements can provide some examples of this process.

First, consider forward movement. Begin from CHOKURITSU SHIZENTAI, i.e. a standing natural posture where the weight of the KOSHI is resting on the two legs in a balanced way. If one moves the KOSHI forward, one's body weight would crumble forward (unless the head is pulled backward to balance it). In order to control this destabilization of the body weight, one leg will tend to move forward. A smooth repetition of this sequence creates a smooth forward movement (ZENSHIN UNDO).

Conversely, if from CHOKURITSU SHIZENTAI one were to pull the KOSHI backwards, the body weight would crumble backwards unless one leg moves backwards. The repetition of this is backward movement (KOTAI).

Similarly, if from CHOKURITSU SHIZENTAI one were to shift the KOSHI to the right side, the body would crumble towards the direction of the KOSHI shift. In order to maintain one’s balance, the right leg must move toward where the KOSHI has shifted. Furthermore, if the other leg then follows, it would create a side shift movement.

Let us consider a second example, starting again from CHOKURITSU SHIZENTAI. If one twists the KOSHI to the left, it becomes evident that the KOSHI can move only up to a certain point without beginning to pivot the feet. Continuing to twist the KOSHI further to the left, beyond this point, causes the tip of the toe to begin to move in the same direction as the KOSHI’s movement.

Eventually, once the KOSHI twists and the feet pivot as far as possible, the toes and the KOSHI will wind up pointing in almost the same direction. (Note that the “direction” of the KOSHI is defined as the direction the TANDEN is pointing). This is especially true for the back leg (in this example, the right leg). Consequently, the whole body turns to the left and automatically creates the left natural posture (HIDARI SHIZENTAI).

Let us consider a third example beginning from a SEIZA (sitting straight) position. From SEIZA, one begins to rise by first sitting on one's toes and then, keeping the knees on the floor, stretching the KOSHI. From this position, move the KOSHI forward and step forward with the right leg so the knee assumes an upright position.

One can easily stand up from this position by stretching the backbone and the back muscles, and creating a posture in which three parts of the body form 90 degree angles: the inside angle of the upright knee, the inside angle of the knee on the floor, and the outside angle of the sole of the foot (which is already aligned vertically on its toes) and the heel (including the Achilles tendon). If the tips of both toes are pointing in the same direction as the KOSHI, then by simply straightening the rear leg and thereby extending it, one can easily and quickly rise to a standing position.

Once standing up, one's basic posture should be as follows: the right knee should be slightly bent and the lower leg (below the knee) should be aligned vertically. The rear leg should be stretched so as to function as a support stick (SHINBARI BO). Finally, the upper body (with a stretched back) should be aligned properly on the KOSHI such that the two legs evenly support its weight. This form is the strongest standing posture, and is especially critical at the final moment of a technique when one projects the maximum output of power into the opponent. Therefore, when one has just finished executing a technique, one should be in this posture.

Another feature of this posture is that if the front leg takes a long stride (and therefore there is sufficient distance between the front and back feet), it is easy to immediately lower one knee to the floor into an equally formidable and strong posture. Thus, when one wants to use a dynamic technique that employs a quick movement from a standing to a (one knee) kneeling position, it is important that there be an adequate span between the feet. If this is done, one will be able to correctly perform the movement required by this type of technique.

In all these examples, we see that all body movements are triggered by a KOSHI movement which, in turn, causes a weight shifting, and then, if balance and stability are to be re-established, necessarily leads to a compensating movement by both legs and feet. This is the principle of body movement (UNTAI NO GENRI).

|

|

Art. 9

Greetings from Ronin Dojo in Poland

By Mariusz Kantek

Dojo-cho Ronin Dojo, Poland

Hello everyone.

The past year 2023 was a very important year for our dojo. On November 1 we became a Full Member dojo of Shin Kaze, which we are very happy about.

We train all year round and try to develop.

On December 9 - 10, 2023, we attended a seminar at Aikido Chrzanów with two Shihans:

Roberto Bollero - 7th dan and Jochen Maier - 6th dan, pictured in the lower picture in the middle and secod from the right respectively.

We hope that next year will be equally fruitful, or perhaps even more so.

Greetings and we wish everyone joy and peace in 2024.

|

|

Art.10

Using digital platforms after the pandemic

By Leonel Sánchez Sotolongo Fukushidoin

Dojo-cho Kan Sho Ryu Dojo, Cuba

One of the positive experiences that COVID-19 left us with despite the physical distancing that we had to assume, was the adoption of the use of digital platforms as an alternative to not stop doing Aikido, and to be able to share with fellow practitioners or even with aikidoists from other latitudes.

After returning to the dojos in person and beginning systematic practice, this option was maintained and more and more people are using it, in order to achieve greater closeness between members of organizations, at times in which we all suffer the effects of a global economic crisis that makes it impossible to travel regularly.

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance also took this approach, and today its member dojos have benefited from participation in hybrid seminars (in-person and online) so that we can receive the teachings provided by high-level instructors.

The Kan Sho Ryu Dojo of Cuba deeply appreciates this opportunity and urges all those who have not tried it yet to experience this initiative.

"United we advance further."

|

|

Art.11

Congratulations to our most recent Full Member dojo

We are pleased to announce that the following dojo have been granted Full Member status as of February 1st, 2024:

- Triangle Aikido in Durham, NC, USA, directed by sensei Charlene M. Reiss, godan.

- Sanshin Dojo in Cumaná, the capital city of the state of Sucre, Venezuela, directed by sensei Everest Guix Fermín, sandan.

- Dojo Kasoku Armirjos, member of Alianza Aikido Argentina, in the city of Presidente Derqui in the Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, directed by sensei Jose Jeronimo Masiero, shodan.

- Dojo Kamn Pilar, member of Alianza Aikido Argentina, in the city of Pilar in the Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, directed by sensei Guillermo Ariel Maldonado, shodan.

- Art of Peace Aikido, in Stone Ridge, NY, USA, directed by sensei Annette Schediwy Mackrel, rokudan and sensei Ralph Legnini, rokudan.

- Joshua Tree Aikido Collaborative, in Yucca Valley, CA, USA, directed by sensei Janice Taitel, yondan.

Our warmest congratulations!

|

|

Art.12

Lorem ipsum

By/Por Author Name

Dojo-cho Dojo Name, Country/Pais

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur magni dolores eos qui ratione voluptatem sequi nesciunt. Neque porro quisquam est, qui dolorem ipsum quia dolor sit amet, consectetur, adipisci velit, sed quia non numquam eius modi tempora incidunt ut labore et dolore magnam aliquam quaerat voluptatem. Ut enim ad minima veniam, quis nostrum exercitationem ullam corporis suscipit laboriosam, nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit qui in ea voluptate velit esse quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum qui dolorem eum fugiat quo voluptas nulla pariatur?

|

|

Art.13

Lorem ipsum

By/Por Author Name

Dojo-cho Dojo Name, Country/Pais

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur magni dolores eos qui ratione voluptatem sequi nesciunt. Neque porro quisquam est, qui dolorem ipsum quia dolor sit amet, consectetur, adipisci velit, sed quia non numquam eius modi tempora incidunt ut labore et dolore magnam aliquam quaerat voluptatem. Ut enim ad minima veniam, quis nostrum exercitationem ullam corporis suscipit laboriosam, nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit qui in ea voluptate velit esse quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum qui dolorem eum fugiat quo voluptas nulla pariatur?

|

|

Art.14

Lorem ipsum

By/Por Author Name

Dojo-cho Dojo Name, Country/Pais

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur magni dolores eos qui ratione voluptatem sequi nesciunt. Neque porro quisquam est, qui dolorem ipsum quia dolor sit amet, consectetur, adipisci velit, sed quia non numquam eius modi tempora incidunt ut labore et dolore magnam aliquam quaerat voluptatem. Ut enim ad minima veniam, quis nostrum exercitationem ullam corporis suscipit laboriosam, nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit qui in ea voluptate velit esse quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum qui dolorem eum fugiat quo voluptas nulla pariatur?

|

|

Art.15

Lorem ipsum

By/Por Author Name

Dojo-cho Dojo Name, Country/Pais

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur magni dolores eos qui ratione voluptatem sequi nesciunt. Neque porro quisquam est, qui dolorem ipsum quia dolor sit amet, consectetur, adipisci velit, sed quia non numquam eius modi tempora incidunt ut labore et dolore magnam aliquam quaerat voluptatem. Ut enim ad minima veniam, quis nostrum exercitationem ullam corporis suscipit laboriosam, nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit qui in ea voluptate velit esse quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum qui dolorem eum fugiat quo voluptas nulla pariatur?

|

|

Dear Dojo-cho and Supporters:

Please distribute this newsletter to your dojo members, friends and anyone interested in

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance.

If you would like to receive this newsletter directly, click

here.

|

|

|

|

SUGGESTION BOX

Do you have a great idea or suggestion?

We want to hear all about it!

Click

here

to send it to us.

|

Donations

In these difficult times and as a nonprofit organization, Shin Kaze welcomes donations to support

its programs and further its mission.

Please donate here:

https://shinkazeaikidoalliance.com/support/

We would also like to mention that we accept gifts of stock as well as bequests to help us build

our Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance endowment.

Thank you for your support!

|

|

|

|

|

|