Comments

Header

News from Shin Kaze

January 2023

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance is an organization dedicated to the practice and development of

Aikido. It aims to provide technical and administrative guidance to Aikido practitioners and

to maintain standards of practice and instruction within an egalitarian and tolerant structure.

|

|

Table of Contents

Intro

Introduction

By

Claire Keller

Dojo-cho Bushwick Dojo, USA

Welcome to 2023 Shin Kaze Members!

Let me begin by marking the recent passing of Yoshimitsu Yamada Shihan. For 50 years, his presence shaped a large segment of Aikido in the Americas and Europe. He will be remembered and missed.

The contents of this newsletter reflect the breadth of our membership and our Alliance’s inclusivity. We welcome everyone’s input and thank the authors and artists who contributed their thoughts, tips, drawings and pictures to this first edition of our newsletter for 2023.

In addition to your articles and views, we would like to receive your feedback in the form of letters to the Editor, and want to thank each and every one of you for being members of Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance.

Happy New Year!

|

|

Art. 2

Y. Yamada Shihan passes away

The Board of Directors of Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance joins the Aikido community worldwide in mourning the passing on January 15, 2023, of Y. Yamada Shihan, 8th dan, Chief Instructor of New York Aikikai, Technical Advisor of the United States Aikido Federation and Founder of Sansuikai International.

|

|

Art. 3

Hombu Dojo Announces 2023 Shin Kaze Kagami Biraki Promotions

(Waka Sensei demonstrates at the 2023 Kagami Biraki celebration at Hombu Dojo.)

(Waka Sensei demonstrates at the 2023 Kagami Biraki celebration at Hombu Dojo.)

The Aikikai Hombu Dojo 2023 Kagami Biraki Ceremony took place on Sunday January 8, 2023. A video of the ceremony can be seen here.

A total of 918 people worldwide were promoted. Click here for the complete list.

New Year promotions for the following Shin Kaze members were announced at the celebration:

Rokudan (6th dan)

Manuel Cormenzana Casuriaga - Dojo Manuel Cormenzana - Venezuela

Luis Enrique Silvera Mattos - Asociación Samurai Aikido Kawai - Uruguay

Godan (5th dan)

Jason Perna - Old City Aikido - USA

Yondan (4th dan)

Jennifer Yabut - Old City Aikido - USA

In addition, the following Shin Kaze members were promoted throughout 2022 and their ranks registered at Aikikai Hombu Dojo:

Yondan (4th dan)

Cody Cowan - Aikido of Austin - USA

Eric De Valpine - Aikido of Austin - USA

Alireza Faed - Toronto Aikikai - Canada

Larry Goode - Aikido of Austin - USA

Sandan (3rd dan)

Jason Thomas Ferrell - Aikido of Austin - USA

Nidan (2nd dan)

Omar Dominguez - Zen Bu Dojo Aikikai - Venezuela

Mary Niskala - Framingham Aikikai - USA

Augustus Timothy Norton - Framingham Aikikai - USA

Luis Eduardo Suárez Ruffino - Aikido Kokyu Ho Dojo - Venezuela

Scott Weber - Aikido of Austin - USA

Shodan (1st dan)

David Avery - Aikido of Austin - USA

Franklin De La Hoz - Marubashi Aikido Dojo - Venezuela

Edward Carrero - Aikido Avila Dojo Aikikai - Venezuela

F. Johnymar Castro A. - Zen Bu Dojo Aikikai - Venezuela

Gene Lejeune - Framingham Aikikai - USA

Alfredo J. León P. - Zen Bu Dojo Aikikai - Venezuela

Lester Emilio Machado Martín - Kan Sho Ryu Dojo - Cuba

Wladimir Ismael Martínez Olivares - Aikido Kokyu Ho Dojo - Venezuela

Alex José Medina González - Marubashi Aikido Dojo - Venezuela

Esteban José Sánchez Colombani - Marubashi Aikido Dojo - Venezuela

Leonel Sánchez Sotolongo - Kan Sho Ryu Dojo - Cuba

Our heartfelt congratulations everyone, please keep up the good work!

|

|

Art. 4

Keeping your practice interesting

By Yelitza Cuevas

Toronto Aikikai, Canada

It is not unusual to sometimes feel off and have doubts about your practice, and when that happens, it is only natural to feel resistance about going to the dojo. Over the years, I have noticed periods when it has been difficult for me to find that "thing" that makes me want to train and engage in tasks with enthusiasm. "Hey, you're always there training hard," people may say. Yes, building a routine has helped me go to class without questioning too much, and hard training has become a kind of motto. But what makes me keep going to the dojo? Are building a routine and having a motto enough? It helps a lot, for sure, but I do not think it is enough.

Since 2000, I have practiced Aikido regularly, attended many seminars, and visited dojos in several countries. At some point in that journey, I started to pay attention to my practice cycles and those triggers that promote changes in my inner state, specifically, helpful triggers that have helped me return from "I don't want to practice" to "I love this" again. I have also started to pay more attention to the Aikido journey of individuals who, in my opinion, seem to have managed to keep their practice steady and interesting.

Despite not having conducted formal research on this topic, I can share some useful tips that have helped me stay in touch and increase my intrinsic motivation over the years.

- Have one or two burning questions and make it your purpose to find answers.

We are all at different levels in our Aikido or Iaido journey. The more we walk these paths, the more we realize how much there is still to learn. For many years, I have engaged in the habit of having a couple of active burning questions that become my purpose during practice. For example, a few years ago, my burning question in Aikido was "How do I keep uke moving at all times throughout the technique?" Since 2019, the question has transformed to "What does it mean to keep uke falling even before they touch me?" Answers to some questions can be found in days, others can take years. What matters is the journey we embark on when searching for answers.

- Create small tasks aligned to your purpose.

This is definitely fun. Imagine these two scenarios: in one, you are doing Tenkan mechanically, wondering which technique comes next; in the other, you are doing Tenkan while studying how to relate it to a task aligned with your burning question/purpose. Which one of those scenarios would you say is more interesting? From the outside, an observer may see you going through the same motions, but what is happening inside you is not the same. For instance, in the case of my active Aikido burning question, I have assigned myself a task of paying attention to the distribution of weight on uke's feet to explore their balance. Is the weight on the front or back foot? How and when does it shift? What makes it difficult/easy for them to recover?

- Plan and attend seminars with a purpose in mind.

This goes beyond "I want to have fun and see friends" or "I want to train hard." Having purpose (burning questions) serves as a compass for planning and finding seminars that are meaningful to you. You look at the combination of factors that can help you best explore your questions. In addition, training at a higher intensity with experienced teachers and practitioners can help you deeply explore and revise your burning questions.

- Find your martial arts buddies.

I have been lucky to walk my Aikido and Iaido paths in the company of people with whom I have been able to create a safe space for training and sharing life events. These individuals have contributed to my martial arts and personal growth by challenging me at a technical and intellectual level. They have enriched my life when exploring areas of interest, traveling to seminars together (or meeting them there), and allowing me to witness and even participate in their life journeys. Well, I even got married to one of them! My martial art buddies have been a constant reminder that I am not alone (or weird) in my approach to practice. They have also been my support network in difficult times, such as for example when I am injured or going through a difficult time, or when mat companions stop their practice because of illness or death. Without my buddies, I do not think I would be training today. You can find your martial art buddies if you look.

- Ask your Sensei.

Your teacher has been practicing for longer than you have. Imagine the many burning questions they have had at different levels of their journey. How have they managed? What has kept them going? What are they studying at the moment? Be curious. I know it may feel intimidating to approach them at first, but in my experience, they feel good and appreciated when your wish for connection comes from real interest in their path. They can be a gold mine of information and inspiration!

All these tips are connected and feed on each other. If you have not tried them yet you may be thinking, "Where can I start?" If this is where you are, I invite you to make this your first burning question, the one that can get you started on the path of engaging in purposeful practice.

Happy and interesting journey!

|

|

Art. 5

Some thoughts on Aikido

By Adolfo Calatayu

Dojo-cho Shinka Dojo, Argentina

In Pascal's "Thoughts" (LXVII) we find that "our nature consists in movement; full repose is death." There is a tacit statement here linked to aesthetics: beauty is movement, action; ugliness is beauty at rest.

Doesn't Aikido express in its most absolute sense and meaning the beauty and grace of movement, that is, circularity? (From the Presocratics to the accelerated universe of current cosmology, the concept of circularity has played a fundamental role in the conception of the cosmos. Straight or curved, finite and infinite, opposites that fight each other and that sometimes dialectically give rise to something higher), Kandinsky's statement that "the form is the external expression of the internal content" helps us to approach such a vision from another angle.

The first source that Bachelard takes from Jaspers in the book Von Der Wahrheit (About Truth) is that "All existence is probably round" to propose the hypothesis that in truth "Existence is round." This is equivalent to stripping the image of its roundness, or of the curvature that is the same thing, as a simple geometric abstraction and to consider it as a poetic image, that is, the mental evocation of a happy space that is rooted in the depths of our unconscious, and that represents the very existence of our being. In the words of Bachelard, "This roundness of the self, or this roundness of being that Jaspers evokes, cannot appear in its more direct truth than in purely phenomenological meditation.?

Aikido is joy, beauty, intuition and balance ... sometimes the temptation of reason is inevitable: the structure of explanation. However, it is obvious that the thought about movement is, in fact, a negation of movement, therefore we should pass from a thought of movement that dilutes it, to an experience of movement that founds it, creates it. Movement is not thought. Movement is a fact, the real.

Aikido is movement, or the spiral of change; it is not only a challenge but an opportunity, a possibility of transcendence. What are we talking about? Through the notion of "axis,” of "center," the practitioner is encouraged to discover his own center. This means finding ourselves, stopping foolishly seeking recognition, praise or understanding outside of ourselves; it even means an end to dependent relationships because we no longer try endlessly to please others.

To find our own center is to verify that our behavior, our thinking and feeling are aligned with the meaning of our existence, the objective we have and who we want to be. Finding our own center or to be aligned ultimately means to think, say, feel and do according to a WHOLE the destiny that is only for us. So then, Aikido is an ethic, an aesthetic, an opportunity, a path and probably much more.

|

|

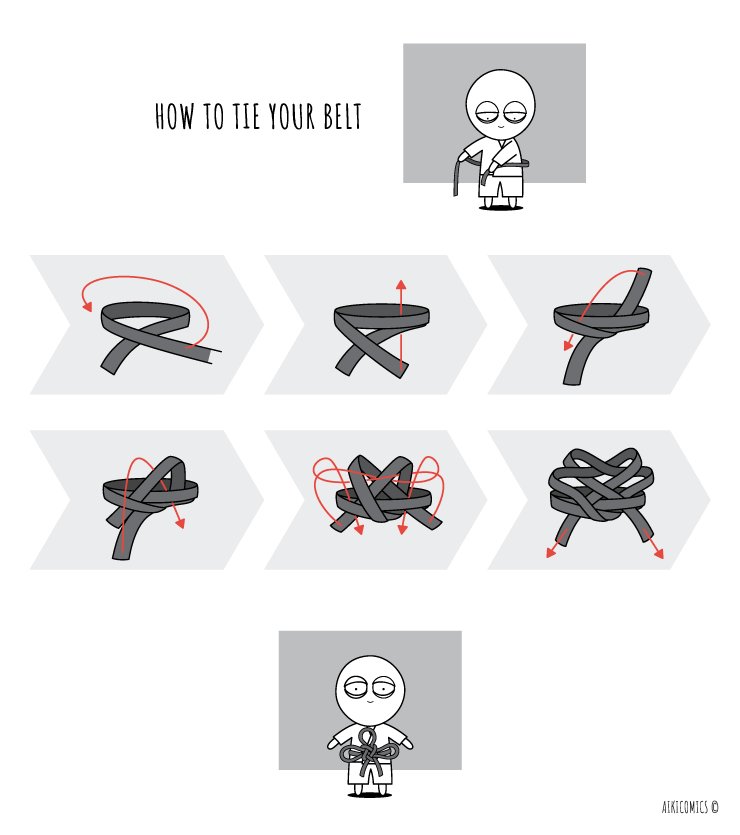

Aiki Comics

Aiki Comics - How to tie your belt

|

© Aiki Comics by Orit Shilon - Used by permission.

Click on the image to visit the site.

|

|

|

Art. 7

Brief overview: Hagakure Dojo in Uruguay

By Pablo Vitelio

Dojo-cho Hagakure Dojo, Uruguay

My name is Pablo Vitelio, I am dojo-cho of Hagakure Dojo in Shangrilá, Ciudad de la Costa, Uruguay. I started practicing Aikido at 18 years old. At that time, through my mother, I met sensei Manuel Cela, who received me at his house in Solymar and told me what our art was about. At that moment I was fascinated. I was further impressed when I met his son Carlos Cela at Nakano Dojo, where his technique and personality in his truly incredible dojo amazed me. So I began to practice in the morning with the excellent teacher Silvana Couse, and in the afternoon with Carlos, and I kept that up until I reached orange belt. The dojo had to move more than once, and I followed it until I couldn’t any more. Financial challenges and a lack of time prevented me from training with Carlos Cela at Fujiyama Dojo in Montevideo until a few years later. In this dojo, in 2009 I obtained my black belt, the same year my first daughter was born. A short time later I had to pause my practice again, given a change in my job that did not allow me to coordinate my schedules to practice and be with my family.

In 2013, with the birth of my second child, the possibility arose to remodel our garage and build an Aikido dojo. Here was my opportunity to continue training and also to share Aikido with my children. The name of the dojo is Hagakure, named after both the book on the samurai culture and the vegetation in front of the dojo making it "hidden behind the leaves."

Given my tasks and responsibilities at home, I couldn’t attend Fujiyama Dojo in Montevideo. At that time I met Sensei Alejandro Nuñez and trained at his dojo Kansha, but I had to stop for the same reasons..

In 2022 I was accepted by Sensei Enrique Silvera into his organization to continue my practice, for which I am very grateful. It is a fortune to be able to attend his classes given his extremely high technical level and experience. He was also the one who encouraged me to open my dojo and link it to Shin Kaze through him, while maintaining my practice in Samurai Dojo.

|

|

Art. 8

Ronin Dojo in Poland

By Mariusz Kantek

Dojo-cho Ronin Dojo, Poland

Editor's Note:We are pleased to announce that Ronin Dojo has recently joined Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance. A very warm welcome!

My martial arts adventure began in 1994 with Aikido and Ju-Jitsu and lasted until 2011, when I started training in Shoshin Dojo Aikido Jaworzno, a member of Sansuikai. When the sensei was absent, as a 2nd kyu I conducted classes for children and adults. In 2020, I received shodan from Yoshimitsu Yamada Shihan. Privately, I have been a postman in the area for 23 years.

Along with others, I left this dojo following disagreements due to the situation there. In the beginning of 2021, I created a new group, Ronin Dojo consisting of a bunch of enthusiasts who want to practice Aikido and cultivate our training without internal systems or games. Wanting to develop further, we applied to join Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance on December 14, 2022, serendipitously on the 47th Ronin Day.

Our dojo is located in the small city of Jaworzno in Silesia, Poland, near Katowice. We have a three-person board that decides on the path we follow with a focus on cultivating traditions and rules. Under my tutelage, we try to follow the ways of the Samurai and Budo. Currently we have eight members in our dojo, and we hope our numbers will increase soon.

|

|

Art. 9

Brief history of Aikido in Brazil

By Baruc Hunck

Dojo-cho Shidokizen Dojo, Brazil

Aikido is one of the most modern manifestations of Japanese Budo, created by Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1969), based on the synthesis of his experiences with different styles and martial techniques, especially those of Daito-ryu Aikijutsu of Sokaku Takeda (1859-1943), as well as the spiritual teachings of Shintoism and his friendship with the leader of Oomoto-Kyo, Onidesaburo Deguchi.

In Brazil, it is possible to observe a series of disputes between different Aikido groups and institutions, but several people are recognized as the pioneers of Aikido in Brazil and the institutions directly or indirectly linked to them invoke as a criterion of legitimacy and symbolic power the figure of their Sensei as the true precursor of the "Art of Peace" in Brazil. Among the pioneers are senseis Reishin Kawai, Teruo Nakatani and Ichitami Shikanai, and among the more well known leaders of large organizations nowadays is sensei Wagner Bull.

Reishin Kawai Sensei

In the early 1960s, a Japanese acupuncturist called Reishin Kawai arrived in Brazil and introduced the practice of Aikido. He was born in Japan, in the city of Yassugi, Shimane Prefecture, on February 28, 1931. While still in his teens, he was affected by severe inflammation in his right knee, which led him to begin studying alternative healing methods such as shiatsu, acupuncture and food treatments. Spurred on by his recovery, he went on to study oriental medicine, as a resident student (uchi deshi) of Professor Torataro Saito.

Professor Torataro Saito had great experience in techniques of health recovery and conservation. His methods embodied the martial techniques that would become Aikido. In the 1920s, young master Aritomo Murashigue attended Professor Saito's clinic and taught him the techniques of the Founder, Morihei Ueshiba. In the 1930s, Professor Saito studied directly with the Founder.

In 1961 Reishin Kawai traveled to Belgium and met master Murashige, who gave him the task of installing Aikido in Brazil. In 1963, Kawai received the Shihan designation directly from the Founder, starting a new phase with the challenge of introducing the teachings of the art in Brazil. He began his journey primarily in the north of Paraná, where he did not find any academies and later founded his first dojo in Sao Paulo.

From 1976 to 1984, Kawai Shihan was vice president of the International Aikido Federation, later becoming general director of the South American Aikido Federation and on October 2, 1975, became the official representative of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo in Brazil. In 1997 he received the rank of eighth dan from Hombu Dojo. He passed away on January 26, 2010.

Teruo Nakatani Sensei

Born on the island of Hokhaido in northern Japan on July 31, 1932, Nakatani Sensei began his Aikido training at Hombu Dojo and had famous training companions such as Hiroshi Tada, Yoshimitsu Yamada, Yasuo Kobayashi, among others. He arrived in Brazil in 1963, to Rio de Janeiro, marking the beginning of Aikido in that city, without any connection with Aikido practiced in Sao Paulo. In 1969 he established the Associação Carioca de Aikido, in the Copacabana neighborhood.

In the early 1970's he had a serious knee injury, which made him leave the practice of Aikido. He then returned to Japan and looked for his college roommate Ichitami Shikanai to take his place at the Rio de Janeiro dojo.

Ichitami Shikanai Sensei

Born on July 30, 1947, in Aomori Province in northern Japan, Ichitami Shikanai arrived in June 1975 in Rio de Janeiro accompanied by Master Yasuo Kobayashi, thus giving continuity to the work started by Nakatani Sensei. Shikanai Sensei's style of practice resulted in a culture shock, as the students more accustomed to Nakatani Sensei's Aikido questioned his style.

One of Master Nakatani's main students, Adelio Andrade, realizing Sensei Shikanai's adaptation problems, helped him to open his own dojo in Niterói. In this place, master Shikanai trained his first black belts, students who helped to spread Aikido in Rio de Janeiro and in other Brazilian states. In 1985 Sensei Shikanai moved to Belo Horizonte, where he still resides and imparts his teachings.

Wagner Bull Sensei

Wagner Bull was born in Londrina, Paraná on May 3, 1949. From childhood he had contact with Japanese immigrants and their culture. He started in Aikido in 1969 under the direction of Professor Jorge Van Zuit (student of Professor Noritaka). In 1970, with Professor Van Zuit's illness, he took over the direction of the dojo. In 1971 he moved to Sao Paulo and trained for five years with teachers Keisen Ono and Reishin Kawai.

He founded the Takemussu Institute and achieved the entity's recognition as a representative of Traditional Aikido in the country through the National Sports Council. This ended the "official recognition" monopoly held by one Aikido organization in Brazil.

Bull Sensei established contact with Hombu Dojo through Yoshimitsu Yamada Shihan who started processing his black belt promotions, and in 1999 gave him 6th dan. In 2002, Wagner Bull had this promotion made official by directives from Japan. Yamada Shihan continued to provide indirect technical support to Bull Sensei's group when invited to Brazil until 2005, when they parted ways due to administrative and methodological differences.

In 2009, he received the title of Shihan from Hombu Dojo, being the second Latin American to obtain this title. Among other achievements, he has written a series of books on Aikido, introduced Aikido in several states in Brazil and organized national and international seminars with world renowned senseis. He currently teaches Aikido at the Takemussu Institute and is one of the main leaders of the Brazilian Aikido Confederation, Brazil Aikikai, an entity he created, working together with master Roberto Nobuhiko Maruyama. This organization has dojos throughout Brazil.

The history of Aikido in Brazil is full of interesting stories and anecdotes, some of which I may write about in a future article. I am very grateful to our colleagues in partner organizations for this research, especially to Leonardo Sodré (godan), Loane Barbosa (mu-kyu) and students at Shidokizen Dojo.

|

|

Art. 10

The Jo and Aikido

By Antonio Aloia and Michael Aloia

Asahi Schools of Aikido, USA

The jo; the short staff; a long stick. Not sharp but blunt. It can't cut a limb off, but it can bludgeon and render the limb useless. However, several direct blows to the head could have a grave outcome as well. The jo is a weapon wielded in Aikido training. But what do aikidoists use it for and what does it symbolize? Is the jo more of an accurate representation of the art than compared to the more popularized katana?

Like the other wooden weapons within Aikido's training context - the bokken and tanto - the jo is used as a teaching tool to better enhance the empty hand portion of the art. By observing the lengths of the jo, bokken, and tanto, each assumes a role of conveying the use and power of proper distance. At a glance, one can quickly tell that the jo, being the longest, is designed to help supplement an aikidoist's understanding of greater distances; specifically, those that may be outside the aikidoist's physical reach, yet not beyond his/her sight or feel. With jo in hand, an aikidoist can learn how to hold an adversary at bay while keeping themselves away from potential danger. Similarly, be it empty handed or with a weapon, the aikidoist can extend their focus and concentration further while remaining balanced and in a strong position, perhaps even seeing a negative situation long before it happens and allowing it to pass or avoiding it altogether, and if need be, confronting it in Aikido fashion. Such awareness can prevent potential harm to fall upon the aikidoist and, therefore, avoid being caught off guard or confused when the situation becomes too close for comfort.

There are multiple ways to hold and present the jo compared to the bokken or tanto. The aikidoist can hold the jo like a sword or a spear, grasp it in the middle, using both ends as both a defensive and offensive tool, or hold it at both ends, using the middle as a block, parry, or even a controlling or trapping component. The front is the back, and the back is the front. There is no top or bottom to the weapon. The uses and combinations are numerous.

Various common traditional practices for the jo exist in Aikido. The first is solo kata - pre-arranged patterns and various forms of grips and strikes; the individual honing of the general mechanics of the weapon. The second is paired practice, kumi-jo, where both uke and nage have the jo and partake in offensive and defensive maneuvers; a choreographed set of moments that help develop timing and distance while executing the mechanics learned in solo practice. There are also jo-tori, unarmed defenses against the jo, and lastly, jo-nage, where nage, using the jo, throws uke, who attempts to grab the weapon from nage. As mentioned previously, all these aspects of practice can help facilitate an understanding of the weapon and of the spacing between uke and nage as well as respective positions to their surroundings. Additionally, these aspects and understandings hammer home the general mechanics of where, when, why, and how to block, strike, parry, or evade. Moreover, paired practice with the jo may help develop a stronger connection to the weapon and to one's partner, paralleling the connection that aikidoists look to keep during empty-handed techniques.

As is the case for paired practice, for both aikidoists, uke and nage, while being in their respective roles, each learns different lessons while partaking in the same exercise. Nage learns how to move the jo correctly and efficiently when someone is grabbing for or holding onto the weapon, as is the case in jo-nage training. Nage also learns how to physically move while having the jo in hand, thereby reinforcing the movement and footwork from empty hand training. Similarly, uke learns how to flow with nage, following the direction(s) of movement and energy as nage attempts to dispatch uke. In a complimentary approach, uke learns how to commit to his/her attack, causing nage's response. And again, both nage and uke learn proper distance and mechanics to both execute technique and take proper ukemi.

In our view, the jo, in essence, represents the physical manifestation of the art and philosophy of what Aikido was designed to be. While it's widely accepted that Aikido is based on Daito-Ryu Aikijujutsu and that, in turn, is based on sword movements, there are limitations to what one can do with a sword. There are basically two general outcomes when wielding a sword: the first is to kill, and the second is to maim. These two options do not seem to fit squarely into the overall philosophy and ideology of Aikido, though a valuable weapon for training, its lack of flexibility thereby suggests that the sword may not be as good an analogy as first considered for Aikido principles.

But what can an aikidoist do with a jo? As mentioned above, it is possible to both strike and maim with a jo strike, one can keep an opponent at bay without inflicting pain or injury; one can manipulate joints and apply non-lethal pressure on different parts of the body, resulting in an off-balancing of uke and minimizing injuries, especially when compared to the sword. Additionally, the jo does not have one set way or method on how to hold it, as does the sword. This versatile nature of the jo represents the versatility and adaptability of Aikido and its way of thinking, thus, its philosophy has a broader scope. Therefore, based on such assessments, in our opinion the jo is more like Aikido than the sword. Fixed positions, limited perspectives, and minimal options with the sword prevent technique and in turn, the art, from being applied to different situations. The sword is a powerful weapon and great training tool. Its presence in Aikido symbolizes the devotion of those who came before and the impact it had on a culture, as does the jo. The jo itself represents the maturation of not only an art form but of a people to be thoughtful, compassionate, and flexible. This, in our opinion, is what Aikido is and what it was meant to be.

|

|

Art. 11

Art. 12

Art. 13

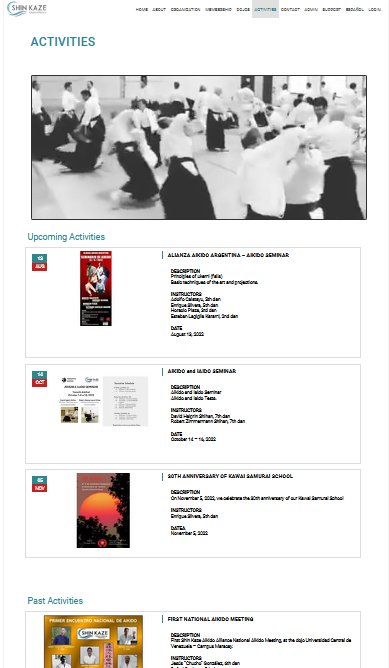

Adding an Activity to the Calendar

Adding an activity or seminar to the calendar on the Shin Kaze website is really easy. All you have to do is fill in a simple Form.

Once the Form is processed, the activity information is published in 2 places on the website:

- In the list of Activities as a summary, as seen in the image above, which shows a thumbnail of the poster, the description of the activity, the instructors and the date.

- In detail on the individual page of the event, which is accessed by clicking on the summary, and shows all the information provided in the Form.

All activities are published in English and Spanish; Shin Kaze handles the translation. Changes or updates to the information can be sent in at any time by re-submitting the above Form or by sending an email to shinkazeaikidoalliace@gmail.com.

|

|

Art. 14

Book Corner: Technical Aikido

By Mitsunari Kanai Shihan, 8th Dan

Chief Instructor of New England Aikikai (1966-2004)

Editor's note: In this "Book Corner" we provide installments of books relevant to our practice.

As continuation from the previous issue, here is Part 2 of Chapter 1 of Mitsunari Kanai Shihan's book "Technical Aikido".

CHAPTER 1 - TRAINING METHODS - (Part 1)

One of the most basic, chronic, and perhaps inevitable problems in practicing Aikido, is that Aikido training can be reduced to an easy going exercise based on excessive compromise between the practice partners (Nage and Uke). This problem arises because Aikido practitioners often base their practice on sincere but ill-founded philosophies and theories. Examples of the many incorrect interpretations of Aikido as applied to practice include emphasizing an idea of an "Aikido style" ambiance, expressing an "ideology" of Aikido, and misconstruing the concept of "harmony".

Because of the importance of correctly understanding the meaning of harmony in the specific context of Aikido, I will give a brief explanation. Keep in mind that I will cover only a tiny fraction of the meanings and aspects of Aikido's harmony.

First, it is important to know that harmony is a central component of Aikido. Most fundamentally, it means harmony with the entire universe, with all existence. In terms of mind and body, harmony simply means that one should equally emphasize each, rather than focusing on one or the other. But in physical terms, harmony has a technical meaning referring to a certain way of using one's entire body in every movement. Applied to a confrontational situation (including training), it is this technical meaning of harmony one must realize in oneself and with the opponent, and create a situation that brings the opponent into harmony with oneself.

Harmony does not mean just getting along with people on the basis of a lowest common denominator, or creating agreement without regard to rules in order to avoid confrontation and maintain an easy going or overly comfortable environment. Harmony, as used in Aikido, does not involve compromising, diminishing, or diluting opposing things and their individual essences. Such an approach waters everything down, sacrifices the essence of things, erodes standards of behavior and attitude and thereby diminishes each individual. Rather, Aikido's harmony brings different -- even opposing -- elements together and intensifies them in a way that drives everything toward a higher level.

It is often pointed out that Aikido permits men and women, adults and children, and old and young to practice together. This is true. It is equally true, but not as frequently noted, that within Aikido there is also room to practice in other ways, for example, to use very hard practice to develop martial techniques. Aikido's breadth and inclusiveness does not mean that its practice is easy, or that those practitioners focusing on developing hard fighting techniques are less important, or less legitimate, than those interested in other of its aspects.

The result of these errors, I suspect, gives rise to the first major problem in Aikido training, which is that many Aikido practitioners have been unable to establish a training method based on the most fundamental understanding of how to use the body to produce, apply and receive power.

What follows is a theory and explanation of how to correctly use the body. It seems to me necessary to articulate in detail this logic of Aikido. It is intended that this articulation of Aikido's physical principles should replace the abstract explanations typically advanced by many practitioners of Aikido and other martial arts.

The Aikido practitioner must understand how the physiology of the body, the very structure of the body, gives rise to rules or principles of how the entire body should most efficiently and optimally function. Correctness of a body movement is judged solely by this criteria: whether the movement, in light of human physiology, utilizes with complete economy all the parts of the body organized in the most efficient possible way. Understanding such a fundamental theory of body utilization must precede explanations of the specific techniques of Aikido.

Any system of body movement must be based on human physiology. The martial arts in general have rules which further define the implications of the human physical structure in the context of combat situations. Aikido, which is aimed at the broadest approach to martial arts, should have an even more precise set of principles.

A specific technique based on these principles will utilize every part of the body, organized and sequenced so as to optimize the generation of power. If this is done, the technique will be correct and will "work". Failure to understand and apply it makes techniques ineffective.

End of Part 1.

CHAPTER 1 - TRAINING METHODS - (Part 2)

One must understand that Aikido training should be solely based on this uncompromisable principle of maximum efficiency arising from human physiology. Armed with this understanding, the practitioner may readily determine whether techniques that may look free flowing and correct are based upon the true principles of Aikido training. Incorrect techniques are all too common due to failure to understand this principle.

The failure to understand the principle of efficient body movement has other implications, for example, that the main groups of techniques characteristic of Aikido (throws, holds, strikes, and thrusts) lack a theoretical consistency and therefore appear overly distinct from each other.

It should be understood that I am not proposing to constrain Aikido in a rigid mold but, on the contrary, I am suggesting that it is necessary to break out of a rigid mold already in existence, a mold made up of formalized bad habits. The results of these bad habits are easily observable in much of what is today called Aikido practice.

There is a second major problem in Aikido training, one which arises in the relationship between Nage and Uke.

Very often training is conducted in a kind of fake confrontational mode without either actually fighting or training in earnest. Because of this, the practitioner typically fails to realize an increasing dependence on the opponent's cooperation. This unwholesome over-cooperation corrupts the relationship between Nage and Uke and, while it may create seemingly dramatic results, it ruins the opportunity to improve one's techniques or train one's eyes.

Because the fundamental principles of Aikido training have not been clearly established, Nages frequently are not applying good and correct techniques that will really throw the Uke; nonetheless, it appears Uke is being thrown. In such cases, the Uke has implicitly agreed to act as though the technique is working regardless of its actual effectiveness (effectiveness is determined primarily by whether the body is used correctly to generate power). Because of this, the issue of whether the technique will work or not has been reduced to utter irrelevance.

Although it should be obvious that a corrupt relationship between Uke and Nage has profoundly negative implications for a martial art, this kind of training is very common. Everyone should clearly understand that as long as people engage in what is, in reality, a fake practice in which they are doing nothing more than merrily playing at being martial artists, the true Aikido will never be learned or understood.

The entirety of the relationship between Nage and Uke is called Sotai Kankei, and is based upon the basic principle of acknowledging that their relationship is fundamentally confrontational. Each of the training partners must abandon thoughts of independence from each other and must accept that the fundamental issue is how to make use of the Aikido knowledge to deal with the Uke through the use of effective, correct techniques based on Aikido's principles.

It is absolutely imperative that each technique employed is real, that is, that each technique handle the opponent by using one's body structure (and each of the five principal parts of the body) in a dynamic and optimally efficient way.

If people were to understand these points, and could use them as the basis for their Aikido practice, the door to understanding would open. It is through this door that the practitioner must pass in order to learn how to execute the true Aikido in a rational manner taking into account all aspects of the body's principles and Sotai Kankei. Without this, the practitioner will be doomed to patching together makeshift and incorrect techniques.

Note on terminology: The words Uke, opponent, other, and partner are closely related, but each has a specific meaning. If one is being attacked, or in a confrontational situation, the word "opponent" (or Aite) is most appropriate. The term "other" is like opponent, but adds a connotation of including everything other than the self, e.g. the concept of Ma-ai or the distance between the self and other. When we are describing the practice of techniques, including taking Ukemi, then it makes most sense to say "Uke". Finally, there is the term "partner" which is most appropriate when describing exercises (as opposed to techniques), for example stretching the back, or practicing Tenkan movements.

|

|

Dear Dojo-cho and Supporters:

Please distribute this newsletter to your dojo members, friends and anyone interested in

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance.

If you would like to receive this newsletter directly, click

here.

|

|

|

|

SUGGESTION BOX

Do you have a great idea or suggestion?

We want to hear all about it!

Click

here

to send it to us.

|

Donations

In these difficult times and as a nonprofit organization, Shin Kaze welcomes donations to support

its programs and further its mission.

Please donate here:

https://shinkazeaikidoalliance.com/support/

We would also like to mention that we accept gifts of stock as well as bequests to help us build

our Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance endowment.

Thank you for your support!

|

|

|

|

|

|