Comments

Header

News from Shin Kaze

April 2025

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance is an organization dedicated to the practice and development of

Aikido. It aims to provide technical and administrative guidance to Aikido practitioners and

to maintain standards of practice and instruction within an egalitarian and tolerant structure.

|

|

Table of Contents

Introduction

Introduction

A warm welcome to the April 2025 edition of the Shin Kaze newsletter, once again providing its readers

with an overview of the diverse cross section of our membership.

In this issue, we include

an article by a Romanian instructor who likes to "play with swords", who shares her experience and personal perspective

on practicing Aikido as a woman and celebrating the empowerment and sense of community it brings;

an article about a unique and beneficial program at The Art of Peace dojo, which promotes family unity,

body awareness, and empowerment;

an article by the instructor of Venezuela Aikido Kokyu Ho Dojo reflecting on the significance of the recent

promotions to sandan of two of his students;

a new Book Corner installment of Kanai Sensei's treatise, "Technical Aikido," with the second part of chapter 5

on ukemi;

and

the first part of a thoughtful article on how Aikido struggles to find its identity in the modern world.

Please enjoy this issue, which we hope will motivate you to contribute an article or two of your own to upcoming newsletters.

|

|

Art. 2

The International Unruly Women's Day

By

Roxana Gramada

Shidoin, Aikikai Romania

I never played with swords as a child, nor do I recall ever wanting to. But no one ever encouraged me to try, either. Swords existed only in fairy tales, where Prince Charming fought the Dragon for the Princess. But even Prince Charming would abandon the sword for a fair fight—at least that’s how I remember the story went. Either way, the Princess didn’t even get to the vicinity where the sword was on window display at the local store. Not even close.

And strangely enough, it took me years to realize that, in fact, I do enjoy playing with swords. Many years.

To figure out what you like or what you want is no easy feat. Especially when you work your way out from under avalanches of expectations. From generations of parents, grandparents, fairy tales, or silent assumptions floating in thin air. To fit in. To speak politely and only when asked. To be nice. Blonde hair seems to help (not that there’s anything wrong with that).

I stepped into a dojo twenty plus years ago, after much hesitation, just to take a look. I don’t remember seeing any other women, and the men didn’t seem particularly welcoming. They fell noisily onto hard mats, occasionally letting out short sounds.

My brother had been practicing aikido for years and enthusiastically tested his techniques on my wrists. I never quite got what he was doing, though he did wax technical about it—something about forming a “Z” and using leverage. He was beaming with younger bro satisfaction. (He could sell anything, even back then.) I wanted in.

Looking back, it was a good decision. For years, I was often (but not always) the only woman on the mat among twenty aikidoka. But aikido isn’t just any martial art. Physical strength matters less. What’s important is spirit, presence. And women have plenty of spirit. I don’t have more strength than a man, but can I be faster? More persistent in search for that stance, that exact point where my partner’s weight becomes irrelevant? In aikido, the body moves in wide, flowing curves. One could even call it feminine expression. Unsurprisingly, finding and staying in one’s center is key here too. And I’ve learned that women can do this just fine, if not more easily than men.

I have been afraid. Many times. Of falling over the arm. Of being thrown in full force. Of a moment’s lapse of attention during bokken practice. Of hurting someone. But few things in this world are more powerful than patience and small steps. And after practicing the same technique over and over, the one you think you’ll never get right simply changes.

Aikido doesn’t happen alone. You have a partner to whom you entrust yourself. Just as they trust you. To protect. To be in harmony with. To be fully present in the technique, all in. Maybe this is the fair fight for which Prince Charming abandoned his sword.

For years, I shared the mat with men with whom I actually have a lot in common, despite being a woman. The same pursuit. A way to sublimate fears or violence—whether experienced, witnessed, or sensed in childhood, on the street, at home, or elsewhere. And the same indescribable joy to share a place where we are equals. Where nothing matters except the technique you’re practicing right now.

And, I must say, I rarely see men happier than my uke during a practice. I secretly believe these men are just waiting for a woman to give it to them. (That sentence might cost me, but it’s worth it. Particularly since I think it’s true.)

Neflix binges with warrior princesses bring girls and women on the tatami, ready to try the forbidden—or perhaps rediscovered—fruit. (In Japan, women also became samurai to defend their families.) And I look forward to the day when the mat will have just as many women black belts as men.

So this is the day I want to celebrate. The Day of Unruly Women. Those who interrupt patterns Those who fight. In their own way, with their own weapons. Who don’t give up and take from life what they want.

And play with swords—whatever they be in their own story. |

|

Art. 3

Bringing All Ages, Sizes and Shapes Together

By

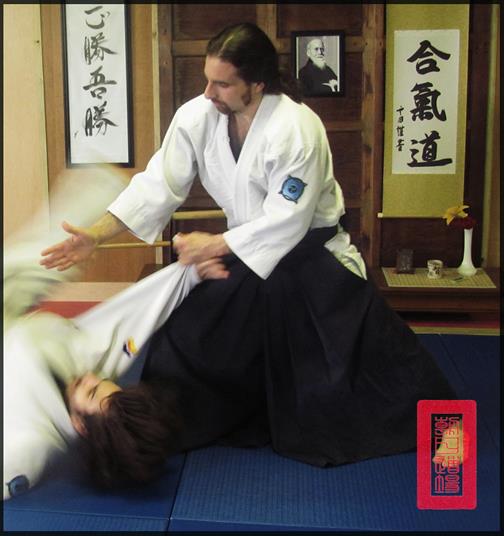

Ralph Legnini

Shidoin, dojo-cho Art of Peace Aikido, Stone Ridge, NY

At The Art of Peace Aikido dojo in Stone Ridge, NY, parents don't drop their kids off for a Saturday morning class - and then go to sit in a café and sip coffee for an hour. Aikido is something that everyone does together!

It's so nice to have such a wide age range in the class - little kids and big grown-ups. Sometimes the kids practice with their own parents, sometimes with other parents, sometimes I pair the smallest kids up with the oldest and sometimes I have all the kids doing techniques together - and all the parents doing the same with the other grown ups.

I don't do any games whatsoever - it is all Aikido - and I often have the kids do randori, which they really excel at. The movement doesn't trigger any emotions or fear or competitiveness or desperation to do some technique or another, and their response is not to tap into any brute strength - their innate responses are quite pure, their young minds are different than adults'.

It's all quite inspiring - and the Saturday morning class is a wonderful part of each week for me.

We have also gotten a number of adult students becoming adult members and taking classes - because they discovered Aikido initially as a parent with their kids. We have one family - the father is a doctor with a medical practice in the same town, and he comes with his wife and two daughters each Saturday - he started also taking adult classes and recently received his 5th kyu promotion.

This is an atypical Aikido class for kids to be in. A quality that kids have - more than adults - is that they are used to doing big movements with their entire bodies, and they are not as inclined to muscling things around. I have found that adults - in early and intermediate stages of learning Aikido, tend to use arm power with smaller whole body motion. Kids are different - and in this way, they approach Aikido with some high level capabilities naturally, and excel at things that adults are challenged with - because adults have to unlearn and release years of upper body tension and strength, and add back that fluid large full body movement that they effortlessly did years ago when they played as kids.

So instead of an Aikido class for kids being a modified, simplified version of an adult class - and then adding in some games that have a kind of Aikido connection - this class is pure dynamic Aikido for a full hour.

It also focuses on body awareness and empowerment, the ability to move freely, the advantage of being closer to the ground - and I often verbalize about how to get one's mind in a good place to do Aikido (open/fearless/calm), a place that they can also learn to make it go when they feel anxious or stressed or scared or overwhelmed in their daily life as a kid. To be able to tap into that state of mind of feeling calm, steady empowerment, instead of melt-downs, frustrations, and feeling stuck in the moment.

I am also teaching them 'self-defense' ability - how to quickly break an adult's grip, and run fast to the other side of the dojo. How to not freeze up, or give up, and to be astutely aware of everything around oneself. To not be intimidated by an adult's size and strength. Knowing that they would be able to do a hard targeted kick/step atemi on the top of an adults foot, followed immediately by a grip release technique and a path to run quickly to a safe spot. That's empowerment.

And most of all, this class embodies togetherness - instead of parents dropping kids off and waiting for them to be done. After being at school and work all week, it's wonderful to get up and have a Saturday morning class where everyone in the family can come do it together. And it becomes a big Aikido family on the mat, ages from 4 to 60, and from 25 pounds to 250!

And at our dojo, a few steps across our parking area is Bodacious Bagels. After the class - lots of the families walk over and have their Saturday morning breakfast - together, which they all look forward to after a lot of fast paced movement and focused concentration. |

|

Art. 4

Aikido Seminar in April 2025 in Santa Clara, Cuba

By Leonel Sánchez Sotolongo Fukushidoin

Dojo-cho Kan Sho Ryu Dojo, Cuba

From April 4th to 6th of this year, nearly 40 Aikido practitioners from Cuba, Venezuela, Spain, Australia,

the United Kingdom, and Canada gathered in Santa Clara to participate in an international Aikido Seminar,

an event that has been held for the third consecutive year in the city of

Santa Clara, the capital of the province of Villa Clara, Cuba.

As in the two previous editions, we had the privilege of receiving teachings from Robert Zimmermann Shihan,

Chief Instructor of Toronto Aikikai and President of Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance, to whom we are infinitely

grateful for giving us the opportunity to continue our martial path under his guidance.

For the first time in events of this nature in Cuba, two foreign practitioners traveled to the island to take

dan grade exams. This gives us great satisfaction, as it demonstrates the seriousness with which we have been

working and the international recognition we have achieved.

We are very grateful to all the participants for their efforts to attend. Work is already underway on organizing

the next edition in 2026, and we are extending our invitation to you now. As always, everyone is welcome. |

|

Art. 5

Reflections

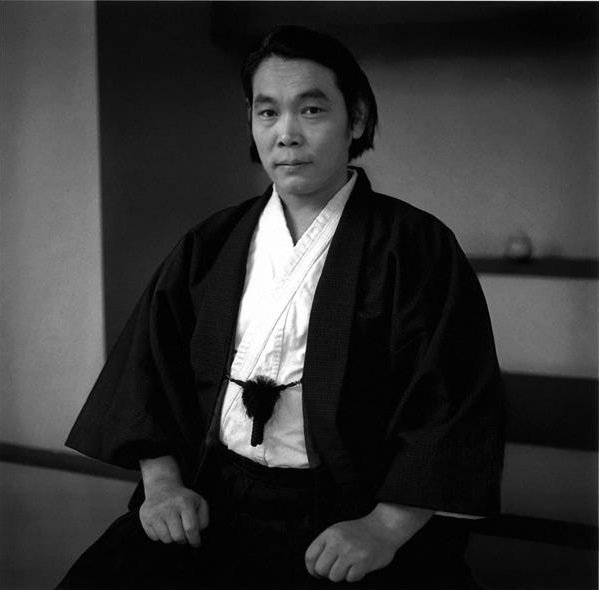

By Rafael Pacheco Shidoin

Dojo-cho Venezuela Aikido Kokyu Ho Dojo, Maracay, Venezuela

I have finally found the time to reflect on the recent achievement of the participation of Jovani Lobo and Luis Suárez, two of my senior students, in the International Aikido Seminar which took place in Santa Clara, Cuba from April 4 to 6, 2025.

The first ideas to emerge are those addressed to Sensei Leonel Sánchez, Dojo Cho of Kan Sho Ryu Dojo, recognizing his warrior spirit to overcome difficulties and achieve for the third consecutive year the realization of this event, also recognizing his empathy and human warmth to facilitate the presence of Venezuela Aikido Kokyu Ho Dojo. Equally significant, is Robert Zimmermann Shihan's invaluable support, manifesting the Mission, Vision, Values and Principles guiding Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance.

Venezuela Aikido Kokyu Ho Dojo, represented by Jovani Lobo and Luís Suárez, today shares immense joy at the approval of their Sandan promotions. This is an achievement that really deserves to be celebrated, but beyond the applause or congratulations, as practitioners of a Martial Art we must stop for a moment to recognize everything they have put on this path: their constant effort, their patience when things did not go as they expected, their humility to learn and, above all, the inner flame of overcoming that should never be extinguished within us, independently of the life circumstances we may face. This rank is not just a reflection of technique; it is a testimony of who you are as a practitioner and as a person.

Aikido, as well-known masters of the discipline have written, is not simply a martial art. It is much more than that: it is a way of life, a philosophy that teaches us to seek harmony in every situation, both on and off the tatami. And that is precisely what makes Budo so special, the true "warrior's path." It is not about winning or losing, being stronger or faster, but of cultivating qualities such as patience, compassion, perseverance and respect. It is a journey inwards, to our own heart, where we discover that the true enemy is not outside, but within ourselves, in our doubts, our fears and our limitations.

However, achieving this rank does not mean that they have reached the destination. Far from it. Rather, they have climbed a rung on an infinite ladder. From there, they will have a broader view, but also more responsibilities. Now they can see beyond, explore deeper techniques and, above all, continue to refine that connection between body, mind and spirit that is the core of Aikido. This new level gives them the opportunity to continue learning, and also to share more with others. Because, as O-Sensei Morihei Ueshiba said, Aikido is not something we keep for ourselves: it is a gift we must offer to the world.

So, as we celebrate this achievement, I also invite you to look forward with curiosity and enthusiasm. Keep in mind that each training is a new opportunity to discover something new, to polish one more technique, to better understand how to apply the principles of Aikido in everyday life. Perhaps one day they will find that a technique that used to be hard to do, now flows naturally, or that a situation that used to drive you out of your mind now you handle it calmly and the most interesting thing is that again there are new questions without immediate answer. That's Budo: growing little by little, without haste, but without pause, becoming better versions of yourselves.

Aikido is not a competition or a race. It is not about what ranks you have achieved, but how you live what you learn in the Dojo. Sandan is an important recognition, yes, but what really matters is how you continue to bring these teachings into your daily lives: how you treat others, how you face challenges, how you seek peace in the midst of chaos. That is the true spirit of Aikido.

So congratulations on this big step. We are proud of the beginning of a new stage for you, full of learning, challenges and moments of inspiration.

We continue on the Tatami, walking together on this wonderful path, honoring the legacy of O-Sensei and remembering that the true master is none other than the very way.

Congratulations!!!!

|

|

Art. 6

Book Corner: Technical Aikido

By Mitsunari Kanai Shihan, 8th Dan

Chief Instructor of New England Aikikai (1966-2004)

Editor's note: In this "Book Corner" we provide installments of books relevant to our practice.

Following is Chapter 5 of Mitsunari Kanai Shihan's book "Technical Aikido".

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Part 1)

In this chapter, I will not address the complexity of defense in general; rather I will limit my discussion mainly to the relationship of Uke to Nage (the "other" or "partner") by focusing on how to fall and/or how to be thrown. Even in this limited examination, we must recognize several key issues.

First, one must understand the proper mental attitude appropriate to those who maintain and pursue the true form of "Bu" (martial arts). In developing the correct approach to ukemi, one must learn to master the ukemi techniques appropriate to any kind of waza (techniques) received from the Nage. This implies both receiving the full force of the Nage's technique, and also making the Nage's technique more refined or "polished".

Therefore one must understand these requirements while maintaining a serious attitude, as manifested in displaying correct manners to the Nage.

The following are simple descriptions of ukemi techniques; however, one must not forget that the basics of learning ukemi require one to practice executing all types of ukemi with a flexible body, a sharp mind, and an accurate judgment of the situation. Also it is essential to abandon an overly dependent relationship to the Nage; that is, a relationship based on a compromise of the principle that Uke and Nage are connected by a martial relationship.

There are several implications of this relationship. For example, Uke must not fall unless Nage's technique works. Also, Uke's technique must not depend on the assumption that the Nage will be kind, or that he will fail to exercise all his options, including kicking or striking the Uke if openings exist.

In training, one must polish one's own technique as well as the technique of one's partner, but at the same time one must maintain an attitude as serious and strict as if facing an enemy. This is the basis for a relationship that moves to higher levels based on a mutual commitment to polishing each partner's Aikido.

CHAPTER 5 - UKEMI - (Part 2)

Koho Kaiten Ukemi (Back Roll ukemi)

The basic requirements of Koho Kaiten ukemi are to be able to take a back roll without hurting yourself when being thrown, and further, to always recognize that the most dangerous element in a martial situation is the person whom you are confronting.

You must practice with the understanding that the bottom line of Bujutsu (martial arts) is to protect yourself from the opponent(s) in any circumstances and at any point in time. This imposes certain technical requirements on the techniques of ukemi.

Failing to understand these requirements can create disastrous consequences for the current practice of Aikido. One can observe this in a commonly seen way to do Koho Kaiten ukemi.

In this case, the Uke begins his Koho Kaiten by stepping back with the inside leg (i.e. the leg closest to the Nage), bending the knee until the knee is touching the floor (in a kneeling posture). The Uke then puts the buttocks down on the mat and first, rolls backward and then rolls forward while touching the same knee on the mat and, finally, stands up.

Doing the backward roll in this way shows an insufficient awareness of the acute dangers inherent in performing all these movements directly in front of the opponent. What are these dangers?

First, you must realize that stepping back with the inside leg means you are exposed to a kick. Furthermore, to lower the inside knee to the ground after stepping back in this way shows a potentially fatal carelessness due to the exposure to a kick, and also to the loss of mobility inherent in this position.

The error of putting down the knee before falling is compounded, after falling, by rolling forward and standing up directly in front of the opponent. This is proof that one is acting independently of the opponent and is in a relationship diametrically opposite to the martial situation, where one is completely involved with the opponent, and where one's actions, to be correct, must acknowledge, and be based on, this interdependence. (The only exception is when practice is restricted by space limitations of a Dojo.) Rolling back while kneeling down and putting down the buttock in front of the other is a position exposing "Shini-Tai" (a "dead body" or "defenseless body") and, therefore, is a position in which you are unable to protect yourself.

As long as Nage or Uke base their approach to practice on an independent relationship with each other, the assumptions underlying their practice will not be consistent with the assumptions of a martial situation. Because Aikido, as a martial art, is based on these (and other) assumptions, one cannot ignore them without compromising its essential nature. Nonetheless, many people have done exactly this, and are practicing an adulterated form which should not be called Aikido because it has been drained of its essential character as a martial art. Approached from such a perspective, Aikido becomes reduced to a barren play, in which one can never produce or grasp anything from the real Aikido.

Therefore, when taking ukemi, do not step back with the leg which is closest to the other! And, do not put down the knee when falling!

What then is the correct way to take Koho Kaiten ukemi? Basically, you must take a big step back with the outside leg and bend that knee without folding the foot so that the bottom of the foot continues to touch the mat. Then put down the same side buttock and do Koho Kaiten by rolling back over the inside shoulder, and then, after rolling over, stand up in Hanmi, take Ma-Ai and face the other.

Depending on the particular technique received from the Nage, it can be appropriate to roll back over the outside shoulder (while still stepping back with the outside leg).

In any event, to perform such correct ukemi, you must utilize the elastic power of the legs sufficiently. In Aikido, the "elastic power" (or "bending and stretching power") is a basic method utilized to produce power or to soften power received from an opponent. In the case of backward ukemi, for example, only by using the elastic power of the back leg after the back roll, can you create the momentum for standing up.

You must use the Achilles' tendon and the hamstring muscle (as well as all other muscles and tendons below' the hip) as a part of creating power when you are being thrown, just as you use them when you are throwing.

Zenpo Kaiten Ukemi (Front Roll Ukemi)

Step forward with the outside leg, i.e. the leg which is further away from the Nage. If, for example, the right leg is the outside leg, extend the right arm forward while pointing its fingers inward and curve the right arm. Then make the outside of the curved arm touch the mat smoothly and roll your entire body forward through, in order, the right shoulder, the curved back, and the left hip.

To complete the roll and rise to standing position, fold the left knee and position the right knee in a bent but upright position. Upon arriving at this one knee kneeling position, by using the momentum of the rolling, put your weight on the ball of the right foot and do Tenkan at the same time standing up and positioning yourself at Migi Hanmi to prepare for the next move. Complete the movement by taking a sufficient Ma-Ai which prepares for the next move of the opponent. Therefore, when one practices this Zenpo Kaiten movement the goal should be to make it low and far (i.e. lower in height and further in distance).

Technical Aikido © Mitsunari Kanai 1994-96

|

|

Comics

Comics - Aikido Animals: The Talker

By Jutta Bossert

The Talker

After the seminar, you know all about them,

their travel plans, their pets, their grandma‘s hip surgery…

On and off the mat, they never stop talking.

© Jutta Bossert - Used by permission.

|

|

Art. 8

A Distinctive Dilemma:

How Aikido struggles to find an identity

in the modern world

(Part 1)

(Part 2)

By Michael Aloia

Dojo-cho Asahikan Dojo, Collegeville, PA

Even during its formation, Aikido has taken on many permutations and multiple interpretations. In brief, its origins are a mixture of physical movements, battlefield ideologies, cultural philosophies, and religious beliefs. More than 80 years after its coining, Aikido continues to take on many forms and interpretations. With the art now moving into a new era where anyone who may have been directly associated with O-Sensei in some capacity will be gone, many look ahead, with concern for the future of the art and its development.

Will there be a massive push to hold on to the remnants of the past and the traditional aspects of Aikido, or will things radically begin to change as a new generation of instructors rise? Will future generations of Aikido practitioners find themselves in an entirely new art form than their predecessors did? Will Aikido still exist?

Many critics believe that Aikido is overdue for a radical change, feeling as though it is a change that should have occurred decades ago. With the growing decline of interest in traditional martial art forms in general, some even feel that such a trend may lead the art, as we know it now, to disappear altogether; that such an evolution is inevitable for its survival. But how does an art move forward when the very definition of what it is, what its purpose is, and how it actually functions as a valuable art form continues to remain in question to outsiders and practitioners alike?

Over the last 20 years, it has been no secret that Aikido has struggled to find its place in the modern martial arts world, especially in America, as MMA has taken such a spotlight along with the rise of the internet. The argument has always been that Aikido is not worth a damn in a street fight and that its practice is a waste of time. In a fists-to-cuffs, knockdown, drag out fight, this may not be entirely untrue, from a certain point of view.

However, the real culprit may lie more in Aikido's own definition and presentation of itself and its practitioners' true understanding of the art, training habits and its purpose, rather than its lack of street credibility in comparison to other styles. Another question to ask regarding Aikido's validity is, was street credibility ever really the art's true goal or a consideration when Aikido was first being conceived? Is such an idea that of subsequent generations attempting to put more to it such as a physical purpose, to compete with other forms and styles?

The old adage when representing or defending aposition is to avoid stating or discussing what something does not have or does; to avoid inadvertently supporting the opposition. However, given the topic of discussion, briefly covering some examples of the above seems prudent to gain a clearer picture of what the art does not offer its seekers.

Aikido is not a fighting or sparring art form. Traditionally, Aikido does not offer a competitive component for its practices. Though there are some forms of Aikido that do include competitions, these forms tend to be hybrids of the original intent of the art and are often frowned upon or ignored by more traditional practitioners. Many will argue that without some form of competition, there is no real way to "pressure test" the techniques and their applications, thus limiting or removing any credibility. Conversely, given Aikido's original design, competition, in the art's current traditional state, does not easily lend itself to the arena without a number of modifications.

Aikido is not necessarily a self-defense form of tactics and techniques. Though there are aspects that can be applied in such a scenario if understood, in general, Aikido is more in line with a self-preservation approach that teaches its practitioners how to get out of the way of a moving train rather than staying on the tracks and meeting it head on.

Aikido does not offer tactics for dealing with a toe-to-toe, physical confrontation. When compared to Western Boxing, Aikido is on the other end of the spectrum. Boxing deals with the engagement of conflict where Aikido tends to focus on the disengagement from or de-escalation of conflict.

Though Aikido is considered a grappling art form, debatably, it does not necessarily equip practitioners for dealing with the clinch. Nor does it traditionally incorporate sweeps and basic takedowns. Styles like Judo and Jujustu tend to provide more reasonable and effective alternatives to such encounters, giving practitioners a stronger level of comfort working in uncomfortably close quarters.

Aikido works with three strike variations primarily; shomenuchi, yokomenuchi, and tsuki, though with its arguably limited range of weapons, the art doesn't dwell heavily in teaching practitioners how to deliver a mechanically sound and effective blow. Karate and other related stand-up styles tend to focus on the necessity of proper striking and anchor their core teachings on generating power and stance, offering practitioners a strong base to work from for exchanging blows.

Based on the above, it would appear that Aikido may be giving critic sentiments a winning position and possibly even proving them entirely correct. This may also be where much of the misunderstanding tends to take place, where Aikido, possibly by its own wrongdoing and undoing, may misrepresent itself unknowingly. There is more to this story than we realize. There is more to Aikido.

(Continued in Part 2.)

To better clarify aspects of Aikido and its training purpose, the following briefly outlines several basic foundational points the art tends to focus on.

Aikido is defined as a way of harmony per the founder of the art, Morihei Ueshiba. However, with reflection, we can come to realize that Aikido was Ueshiba's personal way of harmony that ultimately made up the core of what Aikido has become: his life, his experiences, and his spiritual journey materializing into a physical form from his own view - this one man's interpretation. Over time, that definition or interpretation became the art for those who followed or attempted to follow. Aikido was Ueshiba's world.

Aikido speaks of finding harmony. In truth, harmony can ultimately be found in any endeavor and is not exclusive to Aikido. With Aikido, practitioners are following a path defined by a single man's life interpretation of a martial art including physical and philosophical aspects too. Practitioners are striving to recreate that interpretation for their own benefit, which in itself can be perceived as a futile endeavor as Ueshiba's experience was solely his own. However, with dedicated and diligent practice, aikidoka can begin to create their own way or "do."

The "do" is exclusive to the practitioner. It is how aikidoka integrate, execute, and experience the "aiki" that exists all around them. Each will have a different interpretation, a different experience. Even though some experiences may be similar to another's, they will never be exactly the same. Within the arts, there are often those who spend their time searching for what others have felt or done rather than allowing themselves to feel things for themselves and create their own experiences. The latter is finding harmony within; to do otherwise is disharmony, which, for another study entirely, is the essence of living Budo.

It should be briefly mentioned that the act of inflicting any level of harm, pain, discomfort, or worse on another is in no way a form of harmony, based on its given and/or perceived definition within Aikido and defined by the standards of any sane individual. Such acts are more aligned with disharmony than with harmony itself. Part of the misunderstanding can lie here as there is a bit of discord that occurs in the pursuit of achieving harmony while executing disharmony to another. To say that Aikido does not inflict pain or injury is a misconception as the art form clearly demonstrates such techniques, especially since a majority of Aikido has its roots in aikijutsu/jujutsu. Pain compliance appears, to some degree, in almost all martial art forms.

The harmony sought within the physical confrontation in Aikido is the connection and/or alignment of energies between uke and nage or attacker/defender. Practitioners look to avoid any resistance, working with what is given in that moment, developing the proper mechanics to achieve harmony while moving in and out of disharmony. The harmony sought is the ability to execute techniques without muscle or force.

What Aikido does offer in the way of achieving internal harmony in potentially threatening situations is the awareness to the level of discomfort we choose to either endure or execute. In addition, Aikido offers the discernment to assess the severity of the circumstances we experience and to determine our level of involvementin and/or commitment to those experiences. Harmony is a "connectivity" to what is around us and how we choose to interact with those connections. Aikido teaches us the use of degrees of control and degrees of execution. Practitioners have the capacity to respond accordingly, not impulsively.

On the physical end, Aikido is said to be derived from the use of the sword; primarily an empty-handed application of sword movements but also includes both wielding the sword and defending against it. This approach does offer practitioners a way to develop precision and accuracy while understanding the importance of getting off line and avoiding the attack. The coupling of basic sword practice further reinforces these concepts of distance and projection, primarily working with a partner in the middle ranges. Additional distance ranges, long and short, are studied with the inclusion of the jo and the tanto; both offering similar benefits based on their training.

Aikido teaches the understanding of proper "maai," or distance, and how that distance affects the things we do. Too far away causes over reaching, an unstable position and ineffective technique. Too close, and there is no functional efficiency. Understanding distance gives space. Space gives time, and time gives space. This aspect is the foundation of understanding and implementing the use of proper distance. With empty hands, Aikido generally works in the mid to close range during its practice.

Aikido's physical practice centers on movement and the relation of that movement while in motion with another; two bodies in motion looking to find harmony. The practice is an understanding of what levels of impact that moment has to offer, thus becoming an exploration of self as well as a reflection of a choice in dealing with confrontation. Through its physical training, a moment-by-moment experience is ingested that better equips practitioners on the mental and spiritual levels. The physical aspects are kept simplistic and, at times, stylistic so that such mental and spiritual levels can be achieved in the practitioner's own time. It is not about winning or losing but overcoming- overcoming the obstacles life often places throughout daily life.

Aikido also offers education in moving things that don't want to be moved. Rather than man-handling training partners, subtle changes in stance, center, balance, direction, height, angle, and pressure can make all the difference. The art works to keep a level of individual calm and relaxation that starts with maintaining regular breathing patterns to achieve such a state.

As well, Aikido offers practitioners a way to learn how to fall. Though "ukemi" is commonly translated to falling, more accurately, it relates to one's ability to receive the energy that one comes into contact with - falling is just one part of the ukemi approach. It's about moving and the ability to move in a way that connects and maintains harmony.

More than just a generalized martial art form or even a style, Aikido can actually be defined as a sophisticated developmental tool to gain and build personal skills. These skills are attained through a highly concentrated focus and understanding of: motion and movement, distance and timing, spatial awareness and position, mechanical effectiveness and efficiency, and proper breathing and balance. These elements help practitioners become hyper-in tune with one's own abilities while promoting a calm and stable state of mind, body, and spirit; thus, giving form to the function and function to the form.

With any physical practice, a practitioner's level is determined by the level of commitment given. This reciprocal practice is the basis for the uke/nage relationship and how training partners work to interact with one another while on the mat. This yin/yang model aids in the learning and development of each practitioner, removing resistance so complete immersion can be achieved. The goal is never to hurt or injure another but to raise them up; in their abilities and skills, both on and off the mat. Such practice enhances the learning/teaching experience.

On its philosophical and spiritual intent, Aikido looks to elevate the experience by strengthening the connection. "May the highest in me bring out the highest in you." By intentions and experiences aikidoka can better serve others and enhance training simply by doing - and wanting to do - the best they can at any given moment. By appropriate, harmonious actions and deeds, others will respond in kind - a ripple effect that has positive results. This appears to be Aikido's true way of harmony. It's about what it does to the individual and how that individual makes an impact on others, paying it forward and making a difference with each encounter. Each person has that power.

Aikido offers many people many things - some similar and some different - and that's what makes the art so unique and versatile. However, this may also be why coming to one true universal definition of the art - what is its point and purpose and adapting one method of how it should be practiced - is also so diverse. The art is open to interpretation based on any one individual's or group's experiences. More than an art or even a style, it can be a mindset, an intent. Aikido itself serves as a personal endeavor, a path one ultimately walks alone but with others simultaneously, sharing time and space but in the end, making one's own way of it.

So where does all this leave Aikido and its coming future? Without a crystal ball as many have said, unfortunately, no one really knows for sure. The hope is that the art will continue on for many generations to come. And as it does, it will continue to grow and foster itself as a way for individuals and groups to find one's self and become a better version of said self. Regardless of position, style or even training methods, it can be said that Aikido's true strength lies less in its technique or teaching methods and more in its diversity and ability to modify itself to the situation; giving the seeker exactly what they are looking for.

Maybe the real goal of all this is not to unify to a particular belief and/or standard but to move forward, letting go of all the perceived differences and accept that no two will ever be the same regardless of any effort to make them so. Acceptance allows practitioners to focus their energies on something greater; on bettering themselves and the immediate world around them; finding their own path and living their journey.

|

|

Art. 9

March Aikido seminar in the City of Wells UK with International Women Instructors

By Fiona Blyth Shidoin

Dojo-cho The Wind on the Top of the Mountain, UK

The March Seminar was held in the city of Wells, UK. We had participants from different European

countries as well as Canada and the teachers came from Romania, Argentina, Japan, France, Italy and UK/US.

The weekend of March 8th we were lucky to have beautiful sunshine and the spring weather of the UK with

daffodils out and primroses in bloom.

The intrepid travelers braved many disruptions in their travel, a passport running out, a bomb in Gare de Nord

interrupting all travel to the main airport in Paris, flights arriving from Bucharest at midnight, an

overnight bus from Montpelier to Barcelona all with classes to teach in the morning! I cannot thank the

instructors enough for making such an effort to come and teach us and to give us their time and energy

and share their knowledge.

March 8 is international Women's Day. A day when around the world women are officially recognised for all

their work and achievements which often go understated.

This was the weekend we held the seminar, covering two days, males and females sharing techniques and

Aikido moments together and after the time on the tatami, eating together, cooking together and sharing

stories, ideas together.

We often see flyers and posters offering courses with international teachers, mostly male. I wished to

offer people the chance to learn from female instructors from different Aikido backgrounds as we are all

following the path given to us by O-Sensei. Of course, each of us has seen different interpretations of

how to practice Aikido learnt from our own teachers, and each of us is unique with a different body type

and different personality. This difference is what makes the study of Aikido so interesting and infinite.

The constant questioning of ourselves and searching how can we all work together to find solutions to our

differences in a harmonious way, to me this is what Aikido is about, a time to be together, away momentarily

from the troubles of the world, a moment to create some harmony, some Peace which hopefully will spread,

little by little to others in some form or another.

Please come next year as we are planning to do it all over again and we hope with more instructors and

more people to share! And the possibility of Iaido classes as well!

Save the date: March 7-8, 2026, hope to see you then.

|

|

Art. 10

Art. 11

Art. 12

Art. 13

Art. 14

Art. 15

Dear Dojo-cho and Supporters:

Please distribute this newsletter to your dojo members, friends and anyone interested in

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance.

If you would like to receive this newsletter directly, click

here.

|

|

|

|

SUGGESTION BOX

Do you have a great idea or suggestion?

We want to hear all about it!

Click

here

to send it to us.

|

Donations

In these difficult times and as a nonprofit organization, Shin Kaze welcomes donations to support

its programs and further its mission.

Please donate here:

https://shinkazeaikidoalliance.com/support/

We would also like to mention that we accept gifts of stock as well as bequests to help us build

our Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance endowment.

Thank you for your support!

|

|

|

|

|

|