Comments

Header

News from Shin Kaze

April 2024

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance is an organization dedicated to the practice and development of

Aikido. It aims to provide technical and administrative guidance to Aikido practitioners and

to maintain standards of practice and instruction within an egalitarian and tolerant structure.

|

|

Table of Contents

Introduction

Introduction

A warm welcome to the April 2024 edition of the Shin Kaze newsletter, once again providing its readers

with an overview of the diverse cross section of our membership.

In this edition there is

a New Year greeting that Tamura Sensei wrote welcoming 1991 that is very relevant today, 3 decades later,

a reprint of an article from last year's April issue commemorating the passings of O-Sensei and Kanai Sensei,

a number of articles about Mitsunari Kanai Sensei, in the year of the 20th anniversary of his passing,

a new installment in the Book Corner of Kanai Sensei's book "Technical Aikido",

an invitation to the 2024 Kanai Sensei Memorial Seminar,

a provoking article on Aikido in the western world,

a greeting from Musashi Dojo in Uruguay,

an article on fostering belonging in our dojo communities,

a warm welcome to the latest 5 dojos to join Shin Kaze since the beginning of the year,

and in the Technical Corner a reprint of Shin Kaze's Test Requirements.

Please enjoy this issue, which we hope will motivate you to contribute an article or two of your own to upcoming newsletters.

|

|

Art. 2

Tamura Sensei's New Year Greeting 1991

By Nobuyoshi Tamura Shihan, 8th dan

Foreword

by Fiona Blyth Shidoin

Dojo-cho, The Wind at the Top of the Mountain, UK

"Aikido is the bridge to peace and harmony for all humankind.

The first character for martial art, bu, means "to stop weapons of destruction."

If its true meaning is understood by people all over the world, nothing would make me happier.

The creator of this universe, which is the home for all humankind, is also the creator of Aikido.

The heart of Japanese budo is simply harmony and love."

Master Ueshiba’s view, from "The Spirit of Aikido" by his son, Kisshomaru Ueshiba

Peace.

How in such a conflictual world do we find Peace?

Peace within ourselves, in our families, in our workplace and Peace in the world at large?

The more the news of the world reaches us, the more our concern and thus,

the need for Peace and understanding among different people and nations grows.

At such a time a New Year’s letter written by Tamura Sensei in 1991 appears to be so very relevant today, some 3 decades later.

_____

Happy New Year!

1991 is, in Japan, the third year of the Heïseï era.

A Japanese proverb says: "remain on a rock for three years" which means that if we stay on a cold rock for three years, we always finish by warming it up a little. If we devote ourselves with perseverance to a task, we will always obtain a result.

Tenno chose the name Heïseï for his reign, which means Peace-building, in order to show his own desire and that of his people. Has there been a happy outcome to this wish? The past year has seen the reunification of Germany, the reduction of arsenals of the East and the West, the liberation of Eastern Europe. Thus, it appears that the Peoples’ desire for peace has been heard.

Yet to Yin responds Yang. The problems of Lebanon, the invasion of Kuwait by Iraq leads to the fear of the outbreak of a world war.

Each country has its traditions, its culture, its religion, its character. Each country also believes itself to be alone in its view to be right and proclaims it; which in turn leads directly to conflict.

We, who practice Aikido are clearly aware that all humankind has the same origin. Therefore it is not doctrines, principles, or rules which must be opposed, instead it is necessary to understand what is the common good of humanity, in order to liberate, in some way, what would be the principle, the fundamental human rule and not a doctrine of humanity. It is necessary to respect differences of opinion and also those who defend them because progress is only possible if we work with those who hold divergent opinions. Hence, the wealth of assembled minds opens up a valuable expansion of points of view rather than leading to necrosis and death.

For three years the common desire to build a dojo has motivated us. The original project was gradually refined. Without doubt, and this is my greatest wish, this year will be one of fulfillment.

This year again, we will be together to practice (and sweat) with joy.

Above all, I hope that we will progress one step further and I wish you a wonderful year!

January 1, 1991

N. TAMURA

_____

Ed: The Emperor of Japan or Tennō, literally "ruler of heaven" or "heavenly sovereign", is the hereditary monarch and head of state of Japan.

|

|

Art. 2a

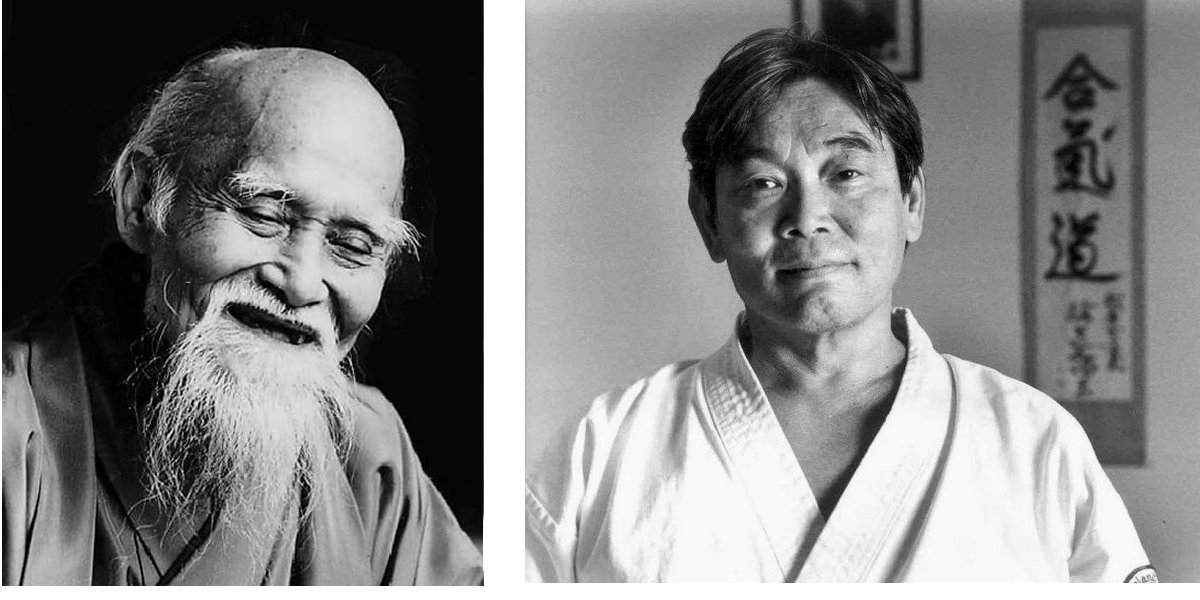

O-Sensei memorial and the remembrance of master teachers

By Jo Birdsong Shihan

Dojo-cho Aikido of Austin, USA

The passing of Morihei Ueshiba, O-Sensei, on April 26, 1969 marked a day of great sadness for the world of Aikido. Fifty five years later there is great joy and happiness at seminars memorializing this date. It is not joy or happiness for his passing but the feeling of love in the hearts of members on the practice mat because of the gift O-Sensei left us. O-Sensei's Aikido is imbued with a loving, harmonious spirit which he taught to his students and is everlasting in the hearts of Aikido practitioners everywhere. O-Sensei's art as a gift to the world should never be forgotten.

The master teachers that traveled the world to bring O-Sensei's teachings to us will never be forgotten as long as we hold the spirit of those teachings high in our minds and our practice. Aikido, the Budo of love, is what O-Sensei taught to his students. As his students became masters in their own right, they followed him and taught us the love in Aikido.

This memorial time for O-Sensei is also an occasion to remember our own teachers who have passed away. One of them is Mitsunari Kanai Shihan (April 15, 1939 - March 28, 2004) of the New England Aikikai. He went to Boston in 1966 and was one of the major developers of Aikido in the United States along with masters Akira Tohei, Seiichi Sugano, Kazuo Chiba and Yoshimitsu Yamada. These shihan taught us the way of Aiki in their own way and have left unforgettable memories with all of us.

My memories of Tohei Sensei and Kanai Sensei include the following. While studying directly with Tohei Sensei in Chicago, I was with the Midwest Aikido Federation. When I moved to Texas, I was technically no longer with the MAF since at that time Texas was considered part of the East Coast Federation (ECF). Tohei Sensei respected the structure of the organization and told me I was no longer in the MAF. I asked if I could stay with him and what I could do to be able to stay with the MAF. He suggested I contact the Shihan on the East coast. Kanai Sensei immediately wrote back to me and said "Stay with your teacher." I appreciated his generous spirit and understanding of the sacredness of the student/teacher bond. Somehow that November Texas was changed in the ECF to an MAF state.

The following story was told to me by a student of Kanai Sensei. One day while Kanai Sensei and his students were practicing Iaido, Sensei gave his family sword to a student to use. They were practicing an advanced Iaido technique involving passing under a beam, and at that time in the dojo there was a real beam above removable shoji screens that they used to practice the technique. The student swung trying to execute shomenuchi and hit the beam. About a foot of the blade broke off from the sword and went flying across the mat, fortunately not hitting anyone. Everyone in the class knew which sword that was, and everything stopped as they looked on, wondering what retribution awaited the student. Kanai Sensei picked up the broken piece, looked at it carefully, and then to everyone's surprise, said: "That sword wasn't any good anyway". He later said the sword was made too rigid which made it prone to breaking. Later, Sensei made a beautiful tanto from the broken piece.

The relationship between teacher and student is a strong one. O-Sensei taught Kanai Sensei well.

|

|

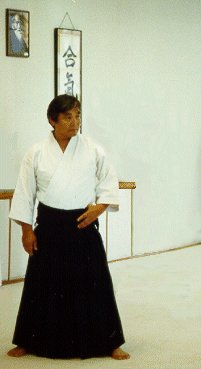

Art. 3

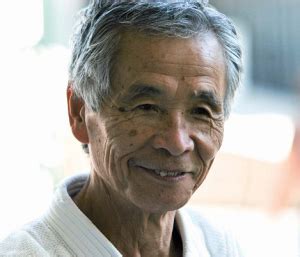

Mitsunari Kanai, Founder of New England Aikikai

April 15 1939 - March 28 2004

Mitsunari Kanai Sensei was one of the last uchi-deshi (live-in students) of O-Sensei Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido.

He moved to Boston in 1966 and founded the New England Aikikai, where he taught until his passing in 2004.

He also taught worldwide at seminars across the US, Canada, Latin America, Europe and Japan.

An 8th dan Aikikai Shihan, he was also skilled in Iaido and had a deep knowledge of the history and craftsmanship of the

Japanese sword.

He passed away on March 28, 2004, having established a legacy of dojos and students who continue to practice his styles of

Aikido and Iaido, preserving his particular focus on precision, timing, and power.

Although 20 years have passed since he parted, his sincerity, generosity, charisma, character and unpretentious demeanor

remain in the hearts and minds of his followers and those fortunate to have met him.

His human traits have left just as deep an impression as his technical prowess.

Miss you greatly Sensei, thank you for sharing of yourself and for your teachings.

|

|

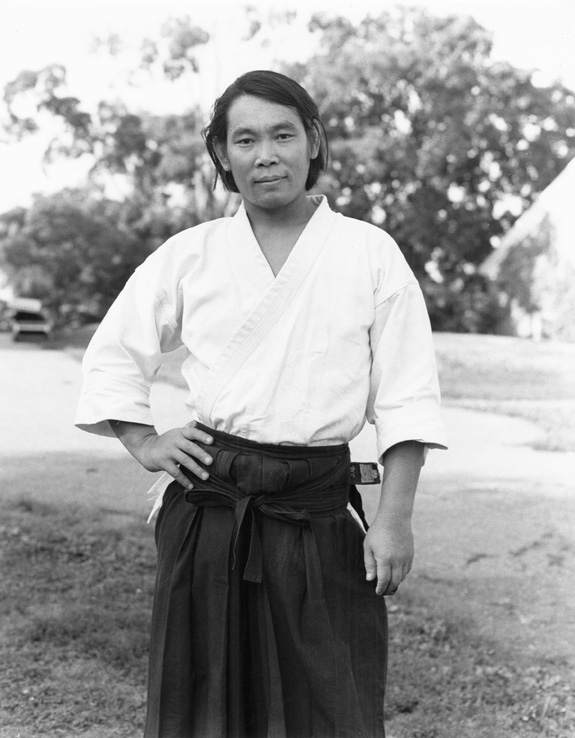

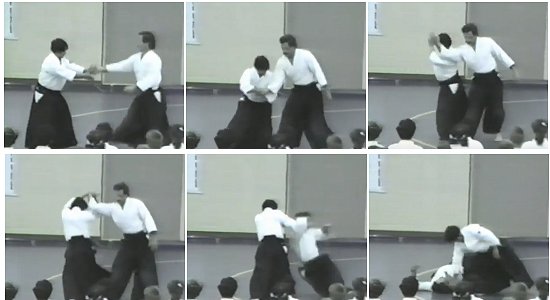

Art. 4

Some things never change

By Paul Sylvain Shihan

Gyaku hanmi katatetori shihonage. Nage: M. Kanai Shihan Uke. P. Sylvain Shihan

In 1973, I returned from an extended stay in Europe where I had the opportunity to train with many interesting Aikidoka.

My undergraduate days had ended along with my failed graduate pursuits.

I decided to return to Boston because I had friends there and a dojo where I knew I would be challenged.

On my first day back at the old Central Square dojo, I went in early to pay my respects to Kanai Sensei.

I was nervous because I wanted to ask lor permission to train with him.

Sensei was hammering in his workshop.

When I came in. he stood up and smiled and walked over to shake my hand.

I hadn't told him of my plans, yet he seemed to sense my question.

"You just stay, practice in my dojo," he said.

Fumbling, I thanked him, feeling warmly received.

I changed into my dogi and went out on the mat to stretch.

Class began, and after warm-ups, Sensei demonstrated ryotetori-tenchinage.

Partners paired off and my aite and I began working at a frenzied pace.

After several minutes, Sensei came over and watched.

Of course, this made us nervous, and we redoubled our efforts to make a good impression.

Sensei continued to watch and then he began to chuckle.

He bowed to us and threw me a few times.

Then he grabbed my wrists for me to throw him.

My tension heightened.

I advanced, stepped through and boom - suddenly I found myself looking up at Kanai Sensei from the mat.

Sensei smiled and asked me to try again.

I got up, even more determined and proceeded to try to throw him again.

I added more force to my movement and vowed to make it work.

As I began , I was sure I felt an opening and charged forward, only to find that same spot on my back, with Sensei

looking down at me.

Two more times I tried, always with the same results.

Then Sensei clapped me on the back and said. "Okay, need more practice. "

Years later, after summer camp, a group of us were diving with Kanai Sensei off of Marblehead. Mass., trying to catch dinner.

I got one flounder and several bites on my hands chasing lobsters. but to no avail.

I couldn't catch any.

Replete with scuba gear, Sensei caught two large lobsters in a manner I can only describe as tricky.

At dinner, as we enjoyed flounder sashimi and steamed lobsters, I asked Sensei what technique he had used to catch the lobsters.

He explained what he did. but the logic escaped me.

Apparently sensing mv confusion. he smiled and said "Need more practice".

I guess some things never change.

To Kanai Sensei: In honor of your thirtieth anniversary, May 1996.

|

|

Art. 5

The Early Days - An Interview With M. Kanai Sensei

By R. Zimmermann Shihan

Dojo-cho Toronto Aikikai, Toronto, Canada

Ed: The following interview took place on June 12, 1999, in between classes at a seminar that Kanai Sensei taught at Toronto Aikikai.

_____

RZ - Sensei, you have been living in the US for over thirty years.

Can you tell us about the early days and about how it was that you went to Boston ?

KS - When I was at Hombu, I got a letter from the President of

Aikido of Boston, Mr. Ray Dobson, Terry's younger brother. The

letter said there were about 60 people practicing Aikido, that they

needed an instructor, and that they could offer the airplane fee, an

apartment and a salary. I forget how much it was, but it was in the

letter. At that time, Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba, who we used to call

Waka Sensei, had gone to New York and stopped in Boston. There he

saw a dojo, which was quite small, but with lots of young people

inside. So he decided "OK, we will send an instructor". That's how

I went to Boston.

RZ - And did it turn out to be exactly like that ?

KS - Not really (laughter) ... when I arrived in Boston there were

only 6 or 7 members in the dojo, the apartment they mentioned was

just a space on the second floor above a factory, and I couldn't get

a salary, because the dojo had no money. Soon after my arrival, the

acting Vice President, Fred Newcomb, had taken over from Ray Dobson.

I later found out that those 6 or 7 members were the Board of

Directors of Aikido of Boston, and that they had voted that they did

not have to pay any dues themselves.

RZ - Don't tell me they also voted that you had to pay dues!

KS - No, but I had to feed myself somehow, so I used the money

from the return air ticket to buy food. So I was stuck and couldn't

go back.

RZ - Did you think maybe there had been a mistake somewhere ?

KS - Yes ... maybe a small one. I later found out that when Doshu

had visited Boston, Fred had brought 60 of his University friends to

the dojo to give the impression that they were practicing (laughter).

Anyway, for a long time I had no salary, so Yamada Sensei decided

to send me to a nice place: New Jersey! (laughter). So I went

there to see about starting a dojo, but already there was somebody

teaching. His name was Bill something- I forget - and I decided

then that if I was going to start Aikido somewhere, I would prefer to

start from nothing. So I stayed in Boston.

RZ - When did things start improving ?

KS - Around that time I could not speak much English, so I did not

know what was going on. I remember that Yamada Sensei had

originally set up my salary to be 50 dollars per week, but even

though I taught all week, and every Saturday and Sunday I taught

private lessons to a family that came from Connecticut, I still could

not earn any income, and I couldn't understand why. Luckily, a

Japanese student came who could speak very good English. I thought

this was a sign from God so I grabbed him, and the first thing I did

was call a meeting of the Board of Directors. That's how I found

out what was going on and about what they had voted and what they

were doing. Without going into details, I was so mad that I fired

the whole Board! After that, people started coming to the dojo and

it got better. Also around that time, another good thing happened to

me. One woman, who was married to a Judo instructor who did not

treat her very nicely, came by and mentioned that Wellesley College

offered a course in women's self-defense. She picked up the phone

and told them "Don't do Judo, Aikido is better". Then I got a job

teaching Aikido at Wellesley College, and that's when I got my first

salary.

RZ - When did New England Aikikai start ?

KS - I started a dojo in Chinatown in November 1966, in what is

called the Combat Zone. Downstairs there was a go-go bar, across

the street there was another go-go bar, and there were hippies at

every corner, so it seemed like a good place for a dojo (laughter).

Everything was so different from what I was used to!

RZ - Do you recall any interesting events from those early days in

the Combat Zone ?

KS - Often there were burglars who broke into the dojo. I

remember one of my students was working as a musician in one of the

go-go bars and once he heard some noises upstairs and thought someone

was breaking in. So he called me and I went there, and everything

was smashed: O-Sensei's scroll, his picture, Doshu's picture, the

desk was broken in half ... (sigh)... When the police came they asked

what we did there, and after explaining, they said that if I caught

whoever did that, I should throw them out the window. I thought

"What a great country!" (laughter). So then I started staying

overnight at the dojo sometimes.

RZ - Did you ever catch anyone breaking in ?

KS - Yeah, I did.

RZ - Sensei, I don't know if that's a fond or a mischievous

smile.

KS - It was a young kid, so although I had my sword in my hand, I

couldn't do anything. Not even cut off his hair. But I really

scared him. After that they never came back.

RZ - Was the neighborhood dangerous ?

KS - All kinds of small things would happen all the time ... but

that's normal.

RZ - How long were you there ?

KS - For about a year. Then we moved to Central Square in

Cambridge, where we stayed for quite a long time. When I went to

the dojo, the first thing I would do was count how many students

there were. They were the same students every day, and I knew

everyone's name, and for a long time I still had less than 10

students. Once I counted 11, and I was so happy! I thought,

"Finally I have more than 10!" (laughter).

RZ - Were you considering returning to Japan ?

KS - My original plan was to return after 3 years, and my dream

was to show O-Sensei to the American people. But about 2 years

after I came to Boston, O-Sensei passed away, so I couldn't fulfill

that dream. Anyway, 3 years passed but the dojo still did not have

many students. When I was teaching in Japan, at Hombu and at Nagoya,

my experience was that at least [you] need 3 years to

[be] able to run a dojo. Nagoya did very well after 3

years, but [in] Boston, after 3 years, nothing was

happening.

RZ- When or what was the turning point ?

KS - The dojo moved again around 1979 to Porter Square in

Cambridge. It was Summer time. Around then I counted the students

again. Now there were about 30.

RZ - Did you know all their names ?

MK - Only the women's (laughter). Then from 1980 to 1985, we

very quickly grew, to about 120, but after that, we never grew again.

When we moved it seemed the old students followed and we got new

ones. Now the numbers seem to be going down, so maybe we will have

to move once more. I remember there was a Taekwondo instructor when

we were in Central Square and again when in Porter Square, and the

same guy is now in the space under our dojo. I guess I will have to

let him know when we move again (laughter).

RZ - When did you decide to start doing Summer Camps ?

KS - The first Summer Camp was in 1967, in New Hampshire. I

thought it would be good to bring students together for practice. I

started teaching it by myself, and then in 1972, I invited Yamada

Sensei and Maruyama Suji of Philadelphia - he is independent now.

After that, the Summer Camp was always with Yamada Sensei.

RZ - So selling your return ticket to buy food seems to have been

the right thing to do.

KS - Yes, but from 1966 through around 1980, I ate enough potatoes

to last me all my life (laughter).

RZ - I'm afraid to ask, but do you still like them ?

MK - Yes. Now I am addicted to them (more laughter).

RZ - So those were the good years, huh ?

MK - Yeah (more laughter). The Japanese and American people

come from such different backgrounds and cultures that early on I got

culture shock. Thinking back, I had such a very hard time ... I got

tricked ... lied to ... I experienced such disappointment in this

country. But always, always, someone helped me, or rescued me, or

supported me, and these too are the American people I live together

with. Now I am very satisfied to live here.

RZ - Can you tell us some more ?

MK - Yes, lots - but I'll save it for later.

RZ - Thank you Sensei for sharing some of your memories and

experiences with us.

|

|

Art. 6

Book Corner: Technical Aikido

By Mitsunari Kanai Shihan, 8th Dan

Chief Instructor of New England Aikikai (1966-2004)

Editor's note: In this "Book Corner" we provide installments of books relevant to our practice.

Following is Part 1 of Chapter 4 of Mitsunari Kanai Shihan's book "Technical Aikido".

CHAPTER 4 - RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN JOINTS AND POWER, AND HOW POWER IS PRODUCED - (Part 1)

We will now examine the relationship between the body's joints and power, and how correct use of the body's joints produces power.

In examining this subject, we can begin to understand the expression of AIKIDO on the physical level, and by focusing on the nature of the body, understand the concept of unification of mind, body and spirit

The concept of unification has suffered because it has usually been a very vague concept. In the past, emphasis on the mind aspect of unification (mainly "how-to-use-KI" ideas) has been used to compensate for the fundamental contradictions and appearance of disunity of AIKIDO's widely varied collection of attacks, joint techniques and throwing techniques

However, as I hope is becoming clear through the previous discussion, it is my belief that by analyzing the workings of the body, a clear and effective logic can be defined and established for AIKIDO practice.

If we use the logic of the physical body as a basis for clarifying what would otherwise be the vague concept of "unification",

we can begin to clarify one's understanding, and escape the ambiguities

in most past concepts. In order to gain this much deeper understanding of AIKIDO, you must learn to use your "entire-self" in AIKIDO practice.

Expressed in physical terms, using your entire-self means that you must use your entire body in performing each movement or technique. Moreover, since the joints are the structures that connect the various parts of the body you must use all of the joints of your body. To do this you must understand the function of the joints of the human body.

There are three important functions of the joints:

First, appropriate and flexible joint movement can soften or avoid a collision with an opponent's power.

Second, joints can create flexibility. Each individual joint has a range of motion, but in order to maximize total body flexibility, one must make all of the joints, including the hip joints, adjust from moment to moment. The more joints that can be adjusted in a coordinated way, the more the body will be totally flexible.

Third, joints can produce power. Muscles create power, and multiple muscles and their associated connective tendons are attached to each joint. When multiple muscles are used in an organized way, the power created necessarily must be proportional to the number of muscles used. This power is manifested through a movement of the joint to which the muscles are connected. If this is true of one joint, then it is better to use two joints than one, and three joints than two, etc. The more joints one uses, the greater the power one can generate and transfer to the opponent.

End of Part 1.

CHAPTER 4 - RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN JOINTS AND POWER, AND HOW POWER IS PRODUCED - (Part 2)

When multiple muscles are used in an organized way, the power created necessarily must be proportional to the number of muscles used.

Let us further examine this concept by taking a conventional CHU-DAN-I-TSUKI (Mid level thrust) attack as an example.

When you try to thrust an object with proper MA-AI (distance), you open both legs slightly wider than SHIZEN-TAI (natural standing posture) and lower your hips. From this stabilized posture, you place your right fist to the waist, extend your left hand straight forward, and then quickly pull your left hand to the left waist.

By using the reactionary power from this rapid pulling motion of the left fist, you strike your right fist forward from your right side at waist level. Just before the right elbow fully stretches out, you twist the fist inward. You hit the object at the moment when you simultaneously tighten your fist and body muscles. At this moment, you keep power in your body by holding your breath.

In analyzing this thrust, it becomes clear that, in addition to the reactionary power from left fist pulling and the twisting power of right fist, the only joint that is effectively used to convert body movement to power is the right elbow joint (and, to a lesser extent, a slight hip twist).

This basic CHU-DAN-I-TSUKI can be explained further as follows: the tension power of multiple muscles surrounding the elbow joint is converted to the speed of the striking motion and this speed, in turn, is converted to striking power. This striking power (or colliding power) is transmitted to the target object when you support the striking power with your own stable body.

However, this basic CHU-DAN-I-TSUKI is not a perfect posture from the point of view of physical dynamics. In fact, if this imperfect posture can be maintained when you strike an object, it means that the reaction from the power which is transmitted to the object is small, and therefore the amount of power transmitted is likewise small.

As long as one maintains this conventional approach to the use of the body to generate power, one can never grasp a logic of AIKIDO. In other words, this approach is a limited, and, more importantly, a non-AIKIDO way, of using the body and generating power. It is a non-AIKIDO way because the final movement is not connected to KI or the release of power.

Moreover, less joints and muscles are used because of the limited use of the KOSHI. Also, holding the breath while moving means power will be held in the body by tight muscles. Conversely, the release of the breath allows the muscles to relax and, by increasing flexibility through relaxation, permits more muscles to participate in the movement. Therefore, release of the breath means relaxation of the muscles, release of power, and release of KI.

I will explain this further. This CHU-DAN-I-TSUKI is done by using one elbow joint, and by utilizing a small hip twist and the body weight. However, the hip twisting and the body weight shifting are not effectively applied because the amount of body weight shifting is so small that it does not require the back foot to be aligned and employed in the creation of the movement. It is the use of the back foot to create power and stabilize the body weight, enlarge the size of the hip and leg movement, and augment the movement through the use of weight shifting that allows one to create a release of power.

To do this technique so as to embody the logic of AIKIDO, one would proceed as follows: If one starts from HIDARI HANMI (left HANMI), the movement should start by twisting the hip to the right. Subsequently, when twisting back the hip, this hip rotational power should be transferred to the shoulder joint rotational power, then to the elbow joint rotational power as well as the arm stretching power. Finally, simultaneously using the speed of this movement to generate power, while applying a snap to the wrist, and putting all the body weight on the left foot, one uses this left foot (which becomes the back foot) as a spring board, to push off from. Thus body weight shifting, rotation of multiple joints, and speed are converted to generate impact power as one strikes the object.

End of Part 2.

CHAPTER 4 - RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN JOINTS AND POWER, AND HOW POWER IS PRODUCED - (Part 3)

The technique of breathing also illustrates two approaches to this technique. Holding the breath tends to keep the muscles tight (rather than relaxed). But, if the breath is released at the moment of the strike several things are achieved, among them, that the muscles are thereby relaxed and therefore capable of generating greater power. Release of the breath correlates with the release of power, as well as release of KI.

The back foot (left foot) must be straight enough to be a "strut" at the moment of impact. For the right arm, the elbow must be facing down and the palm side of SEI KEN (basic fist) must be facing up and the arm must be extended straight.

If the posture is maintained correctly, this CHU-DAN-I-TSUKI can logically yield a much greater instantaneous power than the conventional CHU-DAN-I-TSUKI . In addition, it permits you to maintain sufficient balance despite the reactionary power generated by the impact.

Twisting or reverse-twisting of the hips as an initial starting movement converts the speed of the elastic or rotational motion of the entire body's joints to power, and, accompanied by a good take-off (using the rear leg as a spring board) also converts the force of gravity into power during the body weight shifting. Finally, it converts in an orderly manner, compression of body air to power as KOKYU RYOKU (release of breath). This is the most practical and AIKIDO-like way of producing power.

If the above described striking method (I call it FURI TSUKI from JODAN, i.e. "Swinging thrust from JODAN") is further developed or perfected by training, the exact same motion can be applied to the AIKIDO throwing techniques or joint techniques.

To explain further, it is important to realize that the lower half of the body utilizes two types of movement to produce two different kinds of power. One movement is the horizontal plane rotational movement called KOSHI twist and reverse-twist, and the other is horizontal plane forward movement created by body weight shifting when the foot moves forward.

This power, produced by the lower half of the body, is transmitted to the shoulder where a vertical plane rotational movement of the shoulder joints generates centrifugal force which is then transmitted through the elbow's stretch and twist, and further converted to the power of the wrist snap. Thus different types of power are also produced in the upper half of the body.

Although different types of power are produced in the upper and lower body, it is important to keep in mind that the lower body, in general, produces power from movements in a horizontal plane, and the upper body produces power from movements in a vertical plane. This theory can be applied directly to a technique like IRIMI NAGE. It is absolutely necessary that you organize your thoughts along these lines and apply them to your technique.

I stated earlier that, theoretically, power generated from a movement is proportional to the number of joints involved. However, in reality, when a number of unique kinds of power, produced in diverse parts of the body, are put together, their combination actually generates more than the simple mathematical sum (or total value of power), of each power produced by each joint and its associated muscles. This can be called a synergistic effect.

To utilize one's own body to produce this synergy is the key point of AIKIDO's way of using the body.

As I hope this explanation makes clear, I believe an effective logic, which surpasses past concepts, can be established for AIKIDO practice.

If this logic is used as a basis for analyzing movement, the ambiguity of AIKIDO explanation of the past can be solved; it is no longer necessary to rely on so called "mental" aspects of AIKIDO to explain it. Only after AIKIDO can be logically explained on the physical/body level is it then possible to extend the explanation to the mental and spiritual levels and proceed toward a clear explanation of KI.

As long as ambiguity exists regarding the proper use of the body it is not possible that our investigation into the many aspects of AIKIDO will result in a real understanding of KI. Without clarification of the physical dynamics of AIKIDO, an explanation of KI will be doomed.

Only when an AIKIDO technique contains the characteristics of AIKIDO, consistent with the above-described logic, can we clearly state it is AIKIDO. And because of the existence of this logic in AIKIDO, AIKIDO's application to the use of weapons is possible and, beyond weapons techniques, limitless expansion of technique is possible. This is what makes possible the bright hope of the continuous development of AIKIDO.

End of Part 3.

Technical Aikido © Mitsunari Kanai 1994-96

|

|

Art. 6a

Kanai Sensei Memorial Seminar 2024

By David Halprin

Chief Instructor, Framingham Aikikai, Massachusetts

Please join us this June 14th to 16th for a seminar honoring the legacy of Kanai Sensei.

This year has special significance as it is the 20th anniversary of Kanai Sensei’s passing.

The seminar will once again be at the Prindle Pond Conference Center in Charlton, MA,

about a hour and fifteen minutes west of Boston, near Sturbridge, MA

(google maps link).

As those who’ve joined us before know, the setting is beautiful, the accommodations are simple but comfortable, and the food is

good and healthy.

An Aikido retreat. For three days and two nights, we’ll unplug together and live in the Aikido universe.

(Don't panic! There is WiFi available in the dining hall, so the unplugging need not be total.) We began this seminar in

2017 and intend it to evoke the summer camps that Kanai Sensei organized in the early days of Aikido in the US.

We intend it to be a way for us to preserve the unique style of Aikido we learned from him and our other major teachers, and for

us to relax, socialize, have fun with old friends and make new ones.

The seminar flyer is above, and

information and registration can be found here.

To encourage early registration, which helps us plan, there's a discount if you register on or before May 14th.

If you have any questions please let us know.

Prior Memorial Seminars were amazing events. With your help and participation, this one will be amazing also!

David Halprin

Chief Instructor, Framingham Aikikai

KanaiSenseiSeminar@gmail.com

|

|

Comics

Comics - Aikido Animals: The Hyperactive

By Jutta Bossert

The Hyperactive – Does everything just a little too fast and has waaaay too much energy. Do not feed them coffee.

© Jutta Bossert - Used by permission.

|

|

Art. 8

The Way of Harmony in a Western World

By Michael Aloia

Dojo-cho Asahikan Dojo, Collegeville, PA

There are those things in life that often are a self contained conundrum - where what you see isn't what you get, where what you

think you have is actually something completely different and where things actually get harder the longer you do them. Aikido is one

of those self contained conundrums. Looks can be deceiving when it comes to this modern day Budo, martial way, rooted in samurai lore

and Asian tradition and religion.

Aikido, the Japanese Way of Harmony, can be anything but easy when beginning the journey to master not only its physical skill sets but

surmounting the long-term mental and spiritual challenges associated with attaining an understanding and devotion to its counter-intuitive

philosophies and ideologies.

A Martial Way

Aikido is a Budo, not a martial art. Classified as the latter due to its assumed similar characteristics with other martial styles as

well as its Asian lineage, Aikido is actually a martial way - a way to live one's life, a way to become more, one day at a time.

Martial, "bu", means warlike. "Do" means way. However, in context of Budo and of Aikido, the war we fight is not with others, but with ourselves.

It is not the war without we look to win, it is the war within. The internal struggles we face daily to be a better person, to overcome the

challenges of life and rise to the occasion every time are common to all. This is the real battle, and it is a battle we all fight everyday

for our lifetime. Training involves a honing of the mind, body and spirit. This is Budo. Betterment, happiness, success, strength, peace;

all come from within. In Budo this is achieved through regular training. This training is associated with Aikido.

In the Western world, we often look to solve our problems or fill our voids with external remedies: we buy things, drink things, eat things and throw things way. When those things lose their luster, we start a new cycle and do it all over again, each time, however, the stakes get higher but the relief is shorter and the voids still remain. Budo is a self channeling, self-sustaining way to find contentment and inner peace as well as the inner strength to endure.

Giving Way

Aikido's basic philosophy is to give way and go with the flow. Let that which comes to do you harm pass, just step aside. Rather than fight with it, blend with it. Get out of the way and move on.

For many of us, this is way easier said than done. Western belief is rooted in the "John Wayne" approach: stand your ground, duke it out and the bigger man always wins. This, however, is resistance, and resistance only begets more resistance.

With Aikido's notion of giving way, resistance is eliminated through the use of the movement principle.

Simply not being where the attack is and taking a new position, a new perspective, creates options to redirect, diffuse or escape,

providing a mutually beneficial outcome for all involved.

In an old fashioned "duke it out" scenario, in the end, there is only one man standing.

This is not mutually beneficial.

Though it may appear to be a weaker approach than the "John Wayne" method when confronted with a formidable opponent,

it is actually more a non-submissive state of being, that encompasses a strong sense of self belief, restraint and

the strength to not just fire back, as would happen in a knee-jerk reaction.

Non-submissive means that one does not fall prey to the trappings of conflict and furthers it by engaging in it.

Giving way provides alternatives and an opportunity to view the situation from someone else's point of view.

It also points to the importance of self preservation and removes oneself from the conflict mode to a resolution mode.

Easier Seen than Done

Looks can be deceiving with many things, as is the case with Aikido.

At first viewing, Aikido techniques appear effortless and simple.

But ask any practitioner and their answer will be to the contrary.

Aikido's approach is simple: get out of the way, take the balance and use your partner's energy against them,

disturbing their power and their position, rendering their efforts null and void.

However, in this simplicity lies a sophistication that takes a lifetime to learn.

Just because something is simple does not mean it is easy.

Many of the movements in Aikido are counterintuitive to Western beliefs and natural responses.

Referring back to the "John Wayne" approach of standing one's ground, Aikido would have its practitioners

moving off-line and forward, past the attack, essentially entering it.

Whereas instinctively, when a hostile individual approaches, Western tactics would have us stand there

and "take it like a man", otherwise the choice is to back up and cower away risking judgment and dishonor.

Rather than look to take part in a fist to cuffs exchange of blows, Aikido looks to avoid such displays and seeks position elsewhere. With experienced practitioners, Aikido's series of movements are based in timing, spacial awareness, patience and relaxation, much like how one would most benefit in any daily life situation.

Not a Religion, It's a Way of Life

There are always those who begin a new path in life and in the initial stages of development,

find what appears to be the missing pieces of something they have been searching for.

Without delay, these individuals dive head first into this new found discovery,

often with very little to no knowledge of what they are in for or what will be expected of them.

Their first impression was only a surface experience yet this was enough for them to take the leap.

While there are circumstances where this sort of decision making process pans out to be a good fit

and a lifelong commitment, more often than not, it is the contrary.

It is not uncommon to hear the phrase "Aikido is my new religion" by those new to training.

Aikido does appear to have religious nuances such as particular clothing, ritualistic and ceremonial practices

and a high degree of reverence. However, these are not religious practices but cultural traditions,

martial customs and observances of honor, respect and self discipline.

These traditions and customs are a way of life.

Though Aikido does have some influence from the Shinto religion,

its true heritage resides primarily in samurai history and Japanese culture.

Much like Christianity and Catholicism, Christianity is a much older way of life than that of the

organized religion of Catholicism.

In an organized religion, certain doctrines are followed and adhered to and limitations are imposed,

as opposed to a particular belief or faith that one chooses to live their life by, where there are no limitations.

In this comparison, it is not uncommon for the two to become interchangeable with the other or perceived as

the same thing simply because those who practice Catholicism are most likely Christians of some sorts.

Aikido and Budo have a similar relationship. Aikido is an extension of Budo, as are other martial disciplines

that are more than just a fighting style or method.

Those that promote a way of life, a daily practice that involves a lifetime of commitment, are following Budo.

Aikido is Budo, but its only one vehicle that can be used to achieve such daily practice.

In Conclusion

The true experience of Aikido is not achieved in one or two or even 100 times.

There is no instantaneous gratification or trophy for just showing up.

A commitment to train is a commitment to achieve.

The reward is a better individual; strong in mind, body and spirit.

This can only be realized after one has given oneself to it - surrendering narrow beliefs and limited perspectives.

The challenge is great, the road long and at times hard.

But it is a bountiful road.

The essence of Aikido takes the ordinary and makes it extraordinary by finding the beauty in the simple things,

by finding inspiration in routine and repetition and by finding contentment in serving others as we look to serve ourselves.

|

|

Art. 9

Greetings from Musashi Dojo in Uruguay

Por Mariano Pedraza

Dojo-cho Musashi Dojo, Uruguay

We are Musashi Dojo, a small Dojo located in Punta del Este, Uruguay and directed by sensei Mariano Pedraza, student of sensei Enrique Silvera.

Friendly greetings to all and when you like to visit us you will be very welcome. |

|

Art. 10

Fostering Belonging in Our Dojo Communities

By Charlene Reiss

Dojo-cho, Triangle Aikido, Durham, North Carolina

As a public sector consultant, I have recently encountered research on belonging by Erik Carter, PhD. While his work focuses on inclusion of people with disabilities in schools, churches, and other communities, his concepts have a universal application. The ideas he writes and speaks about resonated with my Aikido side, prompting me to examine our dojo and how we foster belonging in our Aikido community.

As dojo-cho of Triangle Aikido in Durham, North Carolina (USA), I want our dojo to be not just a space but also a community. I want our students to have a place to train and a space where they feel they belong. Using Carter’s ten dimensions of belonging provides an opportunity to ask questions, interrogate our policies and practices, and explore the culture we have created for our dojo members.

Present: To be present, students have to be able to attend classes. Do students face barriers to attendance – finances, scheduling, fitness level? What can we do to reduce those barriers and promote inclusive and authentic participation?

Invited: How do we ask people to participate in our dojo community? How good is our communication so everyone knows what’s happening when? Does everyone feel included when invitations – to classes, seminars, social events – are extended?

Welcomed: Do members feel welcome when they come to the dojo? Are the instructors and other students happy to see them? Is everyone greeted by name and with a genuine smile?

Known: What do we know of our students’ lives on and off the mat? What are their interests? What motivates them to train? What makes them unique?

Accepted: Do all of our members feel that they can be their full, authentic selves at our dojo? Are they accepted in all the ways they are – and in all the ways they are not? Do we accept our students with physical limitations as enthusiastically as those with physical gifts? Do we understand the other demands on their time and energy and appreciate the effort they put forth to train?

Supported: Are we providing support to each of our community members so they can bring their best selves to every practice? Do we provide what they need to learn and to enjoy being part of the dojo?

Cared For: Are we taking care of each other, on and off the mat? Do students feel safe – physically and emotionally – at our dojo? Do we have ways they can bring concerns forward and ensure those concerns are addressed?

Befriended: Belonging to a community is more than showing up and paying dues. It is about being in relationship with others. Do we foster and model healthy relations with and among our members? Do we make the time and effort to socialize, encouraging friendship and care within our community?

Needed: Without students, our dojo is just an empty space. How often do we acknowledge that we need our students to have a dojo, to be able to train, to teach, to learn, and to be a community?

Loved: This might be a tough one for the most serious martial artists among us. Maybe we can’t see how love can coexist with hard training and tactical self-defense. But maybe, just for a moment, we can imagine what a dojo could be, what it could feel like, what it would contribute to our lives, if everyone in it knew they were loved. How would it change what we do and how we see the world if we loved each member of our dojo community, just as they are?

How are you fostering belonging in your dojo? What questions are you asking to build a healthy and inclusive community? I’d love to know: charlene@TriangleAikido.com

_____

Ed: More information about Erik Carter’s research can be found on his website at www.erikwcarter.com.

Belonging graphic copied from Vanderbilt Kennedy Center: Carter explores what it means to be a community of belonging for people with disabilities

here.

|

|

Art. 11

Welcome to our most recent member dojos

We are pleased to announce the following new dojos have joined Shin Kaze as Provisional Members in the past three months:

- Tres Ríos Paraíso Aikikai, located in the city of Puerto Quito, Ecuador, led by dojo-cho Allen Kline, nidan.

- Center Point Aikido, located in the city of Toms River in New Jersey, USA, led by dojo-cho Craig Johnson, shodan.

- Reigi Dojo - Alianza Aikido Argentina, located in the city of Mar del Plata in the Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, led by dojo-cho Eduardo Bitancurt, shodan.

- Niji Dojo - Asociación Morihei Ueshiba del Perú, located in the city of Lima, Perú, led by dojo-cho Miguel Antonio Morales-Bermudez Shihan, nanadan.

- Honsen Aikikai, located in the city of Narbeth in Pennsylvania, USA, led by dojo-cho Andrew Benioff, sandan.

A warm welcome to all!

|

|

Art. 12

Art. 13

Lorem ipsum

By/Por Author Name

Dojo-cho Dojo Name, Country/Pais

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur magni dolores eos qui ratione voluptatem sequi nesciunt. Neque porro quisquam est, qui dolorem ipsum quia dolor sit amet, consectetur, adipisci velit, sed quia non numquam eius modi tempora incidunt ut labore et dolore magnam aliquam quaerat voluptatem. Ut enim ad minima veniam, quis nostrum exercitationem ullam corporis suscipit laboriosam, nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit qui in ea voluptate velit esse quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum qui dolorem eum fugiat quo voluptas nulla pariatur?

|

|

Art. 14

Lorem ipsum

By/Por Author Name

Dojo-cho Dojo Name, Country/Pais

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur magni dolores eos qui ratione voluptatem sequi nesciunt. Neque porro quisquam est, qui dolorem ipsum quia dolor sit amet, consectetur, adipisci velit, sed quia non numquam eius modi tempora incidunt ut labore et dolore magnam aliquam quaerat voluptatem. Ut enim ad minima veniam, quis nostrum exercitationem ullam corporis suscipit laboriosam, nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit qui in ea voluptate velit esse quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum qui dolorem eum fugiat quo voluptas nulla pariatur?

|

|

Art. 15

Lorem ipsum

By/Por Author Name

Dojo-cho Dojo Name, Country/Pais

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas sit aspernatur aut odit aut fugit, sed quia consequuntur magni dolores eos qui ratione voluptatem sequi nesciunt. Neque porro quisquam est, qui dolorem ipsum quia dolor sit amet, consectetur, adipisci velit, sed quia non numquam eius modi tempora incidunt ut labore et dolore magnam aliquam quaerat voluptatem. Ut enim ad minima veniam, quis nostrum exercitationem ullam corporis suscipit laboriosam, nisi ut aliquid ex ea commodi consequatur? Quis autem vel eum iure reprehenderit qui in ea voluptate velit esse quam nihil molestiae consequatur, vel illum qui dolorem eum fugiat quo voluptas nulla pariatur?

|

|

Dear Dojo-cho and Supporters:

Please distribute this newsletter to your dojo members, friends and anyone interested in

Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance.

If you would like to receive this newsletter directly, click

here.

|

|

|

|

SUGGESTION BOX

Do you have a great idea or suggestion?

We want to hear all about it!

Click

here

to send it to us.

|

Donations

In these difficult times and as a nonprofit organization, Shin Kaze welcomes donations to support

its programs and further its mission.

Please donate here:

https://shinkazeaikidoalliance.com/support/

We would also like to mention that we accept gifts of stock as well as bequests to help us build

our Shin Kaze Aikido Alliance endowment.

Thank you for your support!

|

|

|

|

|

|